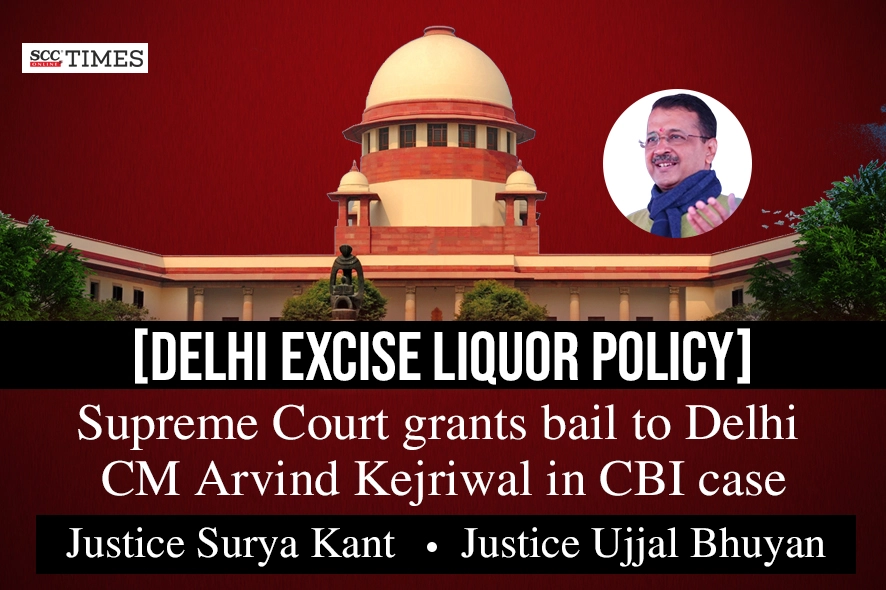

Supreme Court: In a set of two criminal appeals by Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal seeking bail in the Central Bureau of Investigation’s (‘CBI’) case in the Delhi Excise Liquor Policy matter and challenging the legality of his arrest by the CBI, the Division Bench of Surya Kant and Ujjal Bhuyan, JJ. granted him bail. While separate judgments were penned by Justice Bhuyan and Kant, however, there was a concurrent opinion that Kejriwal was entitled to be released on bail, subject to the terms and conditions.

Justice Surya Kant dismissed the appeal challenging the legality of his arrest, holding that arrest by CBI was justified and that there was no procedural infirmity. Justice Bhuyan in his separate judgment differed on this and said that Kejriwal’s arrest by the CBI was perhaps only to frustrate the bail granted to Kejriwal in the ED case. He stated that, when CBI did not feel the necessity to arrest him for 22 long months, he failed to understand the great hurry and urgency on the part of the CBI to arrest Kejriwal when he was on the cusp of release in the ED caseImpugned Decision

The present petition challenged the Delhi High Court’s verdicts dated 05-08-2024 in Arvind Kejriwal v. CBI, 2024 SCC OnLine Del 5305 and Arvind Kejriwal v. CBI, 2024 SCC OnLine Del 5316, wherein Kejriwal’s challenge to his arrest being illegal as well as his application for the grant of regular bail was dismissed, consequently, the legality of his arrest was upheld. He was also directed to approach the Trial Court as when the bail application in the CBI matter was filed before the High Court, the chargesheet had not been filed, however, in the changed circumstances, chargesheet got filed before the Special Judge.

BackgroundKejriwal was arrested by the ED at his residence in connection with the Delhi Excise Policy case on 21-03-2024 after the Delhi High Court refused to grant him interim protection. The Rouse Avenue District Court granted custody of Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal to ED till 28-03-2024. The ED had registered the Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR) on 22-08-2022 pursuant to the registration of the predicate offences by the Central Bureau of Investigation on 17-08-2022 under Section 120-B read with Section 447-A of the IPC, 1860 and Section 7 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 (‘the PC Act’). The CBI had arrested Kejriwal on 26-06-2024, while he was in judicial custody in connection with the money laundering case registered by the ED. The case involved two parallel investigations by the CBI and the ED regarding irregularities in the formulation and implementation of the excise policy of the Government of the National Capital Territory of Delhi (GNCTD) for the year 2021-2022. The CBI registered a case based on a complaint from the Lieutenant Governor of GNCTD and subsequent directions from the Ministry of Home Affairs, alleging offenses under the Penal Code, 1860 (IPC) and the Prevention of Corruption Act.

On 09-04-2024, the High Court dismissed his plea challenging the arrest by the Directorate of Enforcement (‘ED’) for offences under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (‘PMLA’). On 12-07-2024, the Court granted him interim bail in ED’s matter while referring his petition challenging the arrest by the ED to a larger bench.

Whether there was any illegality in Kejriwal’s arrest?Justice Surya Kant

On the question of due compliance with the procedural safeguards enshrined within Section 41-A of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (‘CrPC’), Justice Surya Kant noted that the CBI filed an application on 24-06-2024 before the Trial Court under Section 41-A of the CrPC, inter-alia seeking to interrogate Kejriwal necessitated by new facts and evidence uncovered by the CBI upon further investigation. Referring to the language and intent of Section 41A, which aims to ensure an individual’s appearance through the issuance of a notice, Justice Kant said that it does not outline any express procedure to be undertaken where the individual in question is already incarcerated. He added that there could have been no other way to secure Kejriwal’s physical presence for further investigation, except to seek prior permission of the Trial Court for his interrogation. Section 41A does not envisage or mandate the issuance of a notice to an individual already in judicial custody. Therefore, it was held that CBI followed the procedure. Justice Surya Kant held that Trial Court’s approval of the CBI’s application to interrogate Kejriwal should be viewed as satisfying the essential requirements of Section 41A, as the issuance of a formal notice through the jail authorities would have had an adverse impact on Kejriwal’s rights.

Further, Justice Kant noted that, following the interrogation, CBI moved another application to the Trial Court on 25-06-2024, seeking permission to arrest Kejriwal, which was subsequently permitted by the Trial Court. While addressing whether Section 41A(3) was violated, thereby rendering the arrest per se illegal, Justice Surya Kant explained that it is trite law that there is no insurmountable hurdle in the conversion of judicial custody into police custody by an order of a Magistrate. Thus, Kejriwal’s arrest by the CBI was permissible, in light of the Trial Court’s order. Section 41A(3) allows for arrest, provided the reasons are recorded, justifying the arrest. It was noted that the CBI, in their application dated 25-06-2024, clearly recorded the reasons as to why they deemed his arrest necessary, which were also summarised in the arrest memo.

While considering the applicability of Section 41(1)(b)(ii) of the CrPC in the matter at hand, Justice Kant opined that, the Trial Court upon application of judicial mind accorded its approval to Kejriwal’s arrest for which necessary warrant was issued, hence, there was no occasion for the police officer to form an opinion regarding the existence of valid reasons of arrest. Further, he explained that Section 41(1) opens with the expression that ‘any police officer may arrest without an order from a Magistrate or without a warrant’, and it necessarily means that where a Magistrate has issued an order, the police officer stands absolved from his statutory obligation of forming an opinion. Therefore, Section 41(1)(b)(ii) of the CrPC would cease to apply in the present context, given the order granted by the Trial Court.

Hence, considering CBI’s compliance with Section 41-A of CrPC and the inapplicability of Section 41(1)(b)(ii) of CrPC, Justice Kant held that Kejriwal’s arrest did not suffer from any procedural infirmity.

Justice Ujjal Bhuyan

Justice Ujjal Bhuyan differed from Justice Kant’s view on the necessity and timing of the arrest. As already noted above, CBI case was registered on 17.08.2022. He noted that the CBI case was registered on 17-08-2022 and till the arrest of Kejriwal by the ED on 21-03-2024, the CBI did not feel the necessity to arrest him though he was interrogated by CBI on 16-04-2023. Justice Bhuyan said that only after the Trial Court granted him regular bail in the ED case on 20-06-2024, the CBI became active and sought his custody. He also added that even on his date of arrest on 26-06-2024, the CBI had not named him as an accused. Thus, Justice Kant said that the CBI did not feel the need and necessity to arrest Kejriwal from 17-08-2022 till 26-06-2024 i.e. for over 22 months and that such action raised a serious question mark on the timing of arrest; rather on the arrest itself. Such an arrest by the CBI was perhaps only to frustrate the bail granted to Kejriwal in the ED case.

Reiterating the cardinal principle under Article 20(3) of the Constitution that no person accused of an offence shall be compelled to be a witness against himself, Justice Ujjal Bhuyan said that the respondent authority was wrong for saying that Kejriwal was rightly arrested and should be continued in detention as he was evasive in his reply, for being non-cooperative. Justice Bhuyan added that it would be a travesty of justice to keep Kejriwal in further detention in the CBI case, more so, when he was already granted bail on the same set of allegations under the more stringent provisions of PMLA.

“CBI is a premier investigating agency of the country. It is in public interest that CBI must not only be above board but must also be seem to be so. Rule of law, which is a basic feature of our constitutional republic, mandates that investigation must be fair, transparent and judicious. Every effort must be made to remove any perception that investigation was not carried out fairly and that the arrest was made in a high-handed and biased manner.”

Therefore, Justice Bhuyan held that Kejriwal’s belated arrest by the CBI was unjustified.

Whether Kejriwal is entitled to bail?

Justice Surya Kant viewed that although the procedure for Kejriwal’s arrest met the requisite criteria for legality and compliance, continued incarceration for an extended period pending trial would infringe on legal principles and his right to liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution. Justice Kant noted that Kejriwal was granted interim bail by the Court in the ED matter on 10-05-2024 and 12-07-2024, arising from the same facts. Additionally, several co-accused in both the CBI and ED matters have also been granted bail by the Trial Court, the High Court, and this Court in separate proceedings. Regarding influencing the outcome of the trial, Justice Kant said that all the evidence and material relevant to the CBI’s disposition was already in their possession, negating the likelihood of tampering. Similarly, given his position and roots in the society, there was no valid reason to entertain the apprehension of his fleeing the country. Thus holding that the requisite triple conditions for the grant of bail were satisfied, Justice Kant set aside the impugned decision and directed for his release upon furnishing bail bonds for a sum of Rs. 10,00,000 /- with two sureties of such like amount, to the satisfaction of the Trial Court.

Conditions for grant of bail

-

He shall not make any public comments on the merits of the CBI case, it being sub judice before the Trial Court. This condition is necessitated to dissuade a recent tendency of building a self-serving narrative on public platforms; however, this shall not preclude him from raising all his contentions before the Trial Court.

-

The terms and conditions imposed by a coordinate bench of this Court vide orders dated 10-05-2024 and 12-07-2024 passed in Criminal Appeal No. 2493/2024, titled Arvind Kejriwal v. Directorate of Enforcement, are imposed mutatis mutandis in the present case.

-

He shall remain present before the Trial Court on every date of hearing unless granted exemption.

-

He shall fully cooperate with the Trial Court for expeditious conclusion of the trial proceedings.

On whether the filing of a chargesheet is a change in circumstances of such a decisive nature that an accused would be liable to be relegated to the Trial Court to make out a case for grant of regular bail, Justice Surya Kant said that generally the Trial Court should consider the prayer seeking bail once the chargesheet is filed, since the material that an Investigating Authority may have been able to procure would undoubtedly facilitate that court to form a prima facie opinion with regard to (i) the gravity of offence; (ii) the degree of involvement of the applicant; (iii) the background and vulnerability of the witnesses; (iv) the approximate timeline for conclusion of the trial based on the number of witnesses; and (v) the societal impact of granting or denying bail. However, there can be no straitjacket formula which enumerates that every case concerning the consideration of bail should depend upon the filing of a chargesheet. He said that each case ought to be assessed on its own merits, recognizing that no one-size-fits all formula exists for determining bail.

An undertrial thus should, ordinarily, first approach the Trial Court for bail, as this process not only provides the accused an opportunity for initial relief but also allows the High Court to serve as a secondary avenue if the Trial Court denies bail for inadequate reasons.

Further, he explained that if an accused approaches the High Court directly without first seeking relief from the Trial Court, it is generally appropriate for the High Court to redirect them to the Trial Court at the threshold. Nevertheless, if there are significant delays following notice, it may not be prudent to relegate the matter to the Trial Court at a later stage.

Justice Bhuyan agreed with the conclusion and directions of Justice Kant so far as release on bail was concerned. While giving his views on the impugned decision of the High Court, Justice Bhuyan said that if the High Court thought of remanding Kejriwal to the forum of the Court of Special Judge/ Trial Court, it could have been done at the threshold itself rather than after issuing notice, hearing the parties at length and after reserving the judgment for about a week. Justice Bhuyan stated that though couched in a language which appears to be in favour of Kejriwal, in practical terms it only resulted in prolonging his incarceration for a far longer period impacting his personal liberty.

CASE DETAILS

|

Citation: Appellants : Respondents : |

Advocates who appeared in this case For Petitioner(s): For Respondent(s): |

CORAM :

Kejriwal granted bail in Delhi Liquor Policy case by SC; procedural compliance upheld but arrest timing questioned. ⚖️ #CBICase #KejriwalBail

Ab kya hoga Kejriwal ka achcha khasa naukari kar raha tha bekar fas Gaya