Introduction

While party autonomy is the underlying motif of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996[1] (“the Act”), Parliament has ensured that the Act contains adequate provisions to deal with situations and circumstances which require intervention of courts whenever necessary. One such provision is Section 11 of the Act which apart from granting parties the liberty to devise their own procedure to appoint arbitrator(s) (subject to provisions of the Act) describes the extent and role of courts in appointment of arbitrators. In case of non-appointment in an international commercial arbitration i.e. an arbitration where at least one of the parties is foreign, the party concerned can approach the Supreme Court (with the remedy being before the relevant High Courts in all other cases).[2]

Section 11 of the Act, as originally enacted, envisaged that if one of the parties failed to appoint an arbitrator in terms of the agreement between the parties (or within 30 days of the receipt of a request to do so from the other party, in case there is no agreed procedure), the requesting party could approach the Chief Justice of India and request the Chief Justice to appoint the arbitrator. The appointment would then be made either by the Chief Justice himself, or by any person or institution designated by him for this purpose.

Parts of Section 11 of the Act were amended by Section 6 of the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015[3] (“the 2015 Amendment Act”), which came into force w.e.f. October 23, 2015. The 2015 Amendment Act effectively entrusted the responsibility of appointing the arbitrator to the Supreme Court or any person or institution designated by it. The 2015 Amendment Act also introduced a timeline for the disposal of a Section 11 application by introducing sub-section (13). Notably, this timeline of sixty days from the date of service of notice on the opposite party is only directory and the Supreme Court or the person or institution designated by it are required to make an endeavour to adhere to this time-period.

The Supreme Court has not designated an institution for exercising the powers under the Act and therefore continues to hear Section 11 applications itself. However, pursuant to Section 11(10) of the Act (before its amendment in 2015), the Chief Justice of India formulated ‘The Appointment of Arbitrators by the Chief Justice of India Scheme’ on May 16, 1996 (“the Scheme”) which is still in force. Therefore, the provisions of the Act, the Supreme Court Rules, 2013[4] (“the SC Rules”), and the Scheme govern Section 11 applications.

Section 11 of the Act now stands substantially amended by the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019[5] (“the 2019 Amendment Act”). The amended Section 11 entrusts the appointment of the arbitrator in the arbitral institutions designated by the Supreme Court. These arbitral institutions, in turn, are to be graded by the Arbitration Council of India (“ACI”) (a body to be established by the Central Government pursuant to Section 43-B of the 2019 Amendment Act) – this gradation, according to Section 43-I, will be “on the basis of criteria relating to infrastructure, quality and calibre of arbitrators, performance and compliance of time limits for disposal of domestic or international commercial arbitrations, in such manner as may be specified by the regulations”. The most significant change to Section 11 in the 2019 Amendment Act is therefore that the task of appointing an arbitrator where the parties fail to do so, is entrusted to an arbitral institution (as opposed to the Supreme Court or the High Court, as the case may be), thereby substantially streamlining the process of the appointment of an arbitral tribunal. This article does not delve into details of the amendments brought about by the 2019 Amendment Act, including with respect to the process of gradation by the ACI, or the pool of arbitral institutions that may be selected by it, or the choice of potential arbitrators that each of these institutions may in turn have. The focus of this article is on the changes introduced, to the extent that they would have an impact on the timelines for the disposal of Section 11 applications. However, until the relevant sections of the 2019 Amendment Act are notified, the Supreme Court will continue appointing arbitrators.

One of the principal advantages of arbitration over the more traditional form of dispute resolution is that arbitrations are quick and time-efficient. However, oftentimes the appointment of an arbitrator itself takes substantial time (thereby effectively nullifying this benefit). Despite the amendments to the Act, this initial step has not been made mandatorily timebound, as opposed to, for instance, the entire arbitration process itself (reference Section 29-A of the Act). What is relevant, however, is that the scope of examination under Section 11 by the courts has been confined to an examination of the existence of the arbitration agreement. With this, the Act does envisage a quick and expeditious disposal of Section 11 applications. It may therefore be necessary for the Supreme Court to make structural changes to ensure quick disposal of Section 11 applications.

This article is divided into following parts:

(i) analysis of average time taken for listing of a Section 11 application before the Supreme Court for the first time and average time for final disposal (2016-2019);

(ii) reasons for delay in the first listing and final disposal of Section 11 applications; and possible solutions for streamlining and expediting hearing of Section 11 applications by the Supreme Court; and

(iii) the changes sought to be brought about by the 2019 Amendment Act.

The focus of this article is not the changes proposed to be brought in place by the 2019 Amendment Act (though these are briefly spoken about), but rather steps that can be taken to expedite Section 11 applications that will be filed before the Supreme Court till the time that the ACI is established and the amended Section 11 is acted upon.

I. Time taken for first listing of Section 11 applications and their disposal by the Supreme Court

This article has reviewed the data available on the Supreme Court’s website[6] for the years 2016 to 2019 in relation to Section 11 applications to analyse the average time taken in the appointment of an arbitrator by the Supreme Court. The methodology employed is as follows:

(i) for calculating the number of days for first listing of a Section 11 application, the date of registration of the application by the Supreme Court Registry is taken as the starting point; and

(ii) for calculating the number of days for final disposal of a Section 11 application, the day on which the Supreme Court issued notice is taken as the first day (while the date of service of notice is the starting point under Section 11(13) of the Act (as amended by the 2015 Amendment Act), this information is not available on the Supreme Court website).

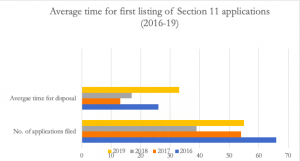

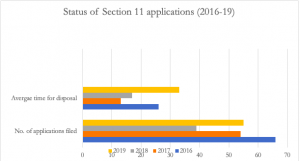

The graphs below indicate the average time taken for the first listing of a Section 11 application before the Supreme Court and the average time taken for final disposal:

The first listing of any application/petition/appeal before the Supreme Court is determined generally by a computer software with minimum human intervention. It will be seen that in 2016, 66 Section 11 applications were preferred before the Supreme Court and the average time for their first listing from the date of their registration by the Supreme Court Registry was 25.86 days. In the following year, 54[7] Section 11 applications were preferred before the Supreme Court. However, the average time for the first listing was almost half the time in comparison to that in 2016 i.e. 12.95 days. In 2018, only 39 Section 11 applications came to be filed which were at an average listed before the Supreme Court within 16.87 days of their registration. In 2019, the average time for first listing of a Section 11 application increased almost two-fold from 2018, i.e. it took 32.98 days for first listing before the Supreme Court.

Insofar as the average days for final disposal of Section 11 applications is concerned, the data paints a woeful picture. In 2016, a Section 11 application at an average would be disposed of in 385.95 days. In fact, till date four Section 11 applications filed in 2016 are still pending. In 2017[8], the Supreme Court took 204.42 days on an average to finally dispose of a Section 11 application and as on date eight applications are still pending. In 2018, the average time reduced to 159 days but fourteen applications are yet to be disposed of by the Supreme Court. Of the 55 Section 11 applications filed in 2019, only 15 have been disposed of yet and the average time for these has been 180.93 days. This analysis reveals that it can take almost six months (if not more) to only get an arbitrator appointed, effectively negating the advantages of choosing arbitration as a mode of dispute resolution.

The data in relation to disposal of Section 11 applications by appointment of arbitrator(s) is as follows:

- Of the 62 Section 11 applications of 2016 disposed of by the Supreme Court, arbitrators were appointed in 43 applications;

- Of the 40 Section 11 applications of 2017 disposed of by the Supreme Court, arbitrators were appointed in 29 applications;

- Of the 25 Section 11 applications of 2018 disposed of by the Supreme Court, arbitrators were appointed in 21 applications; and

- Of the 15 Section 11 applications of 2018 disposed of by the Supreme Court, arbitrators were appointed in 8 applications.

It is therefore critical that the Supreme Court takes steps to expedite the process of appointing arbitrators under Section 11. The next part analyses the reasons for the delay and suggests simple solutions which may help in quicker disposal of Section 11 applications.

II. Reasons for delay in the first listing and final disposal of Section 11 applications and possible solutions

A. First Listing of Section 11 applications

As already mentioned above, the first listing of any case before the Supreme Court is governed by a computer-based software once the Supreme Court Registry has verified it for listing. The steps preceding this include:

(i) filing the requisite number of paper books with the Registry, which notifies defects in the application;

(ii) curing of the defects notified by the Registry and refiling of the application; and

(iii) further scrutiny and final verification for listing.

The Registry treats a Section 11 application on a par with any other petition/appeal/ application filed before the Supreme Court and its scrutiny is not accorded any special status. Therefore, Section 11 applications are scrutinised in their turn along with special leave petitions which form the bulk of the filings before the Supreme Court. The delay begins here and therefore it would be prudent to have rules in place which require Section 11 applications to be scrutinised on a priority basis.

The second reason for delay is the requirement of filing five copies of the Section 11 application in the very first instance, as opposed to three copies in other cases, presumably to speed up the service process once notice is issued by the Supreme Court. Once the Section 11 application is scrutinised and the defects are notified, the lawyer is required to collect the original as well as the copies submitted to cure the defects which can be a time-consuming process if it requires re-numbering of pages and/or making changes in the body of the application. However, if the lawyer is only required to submit the original in the first instance, considerable time could be saved.

The third reason for delay in the first listing of a Section 11 applications could be attributed to the computer based software which presumably has no special function for listing of Section 11 applications. It is submitted that the computer based software could be suitably modified to ensure that Section 11 applications are listed before the Roster Bench within seven to ten days of being verified by the Supreme Court Registry.

At present, the average time for first listing between 2016-2019 is over three weeks. The suggested measures would ensure that right from the filing stage, Section 11 applications move through the machinery of the Supreme Court Registry swiftly and are listed in the shortest possible duration.

B. Final disposal of Section 11 applications

Apart from the adjournments sought by the parties and time constraints faced by the Supreme Court, briefly speaking, the following two reasons are the main cause for the delay in finally disposing of Section 11 applications:

(i) Service of application on opposite party after notice; and

(ii) Listing after pleadings have been completed.

Service of Section 11 applications

The Act does not prescribe any rules for service of Section 11 applications and the same is left to the courts to prescribe. The service of Section 11 applications in the Supreme Court is governed by the SC Rules and the Scheme.

Order LIII of the SC Rules governs service of documents including service of notices. Rule 3 of Order LIII states that service to a party residing in India is to be done by posting a copy of the document required to be served in a pre-paid envelope registered for acknowledgment. The party desirous of service is required to deposit the requisite process fee with the Supreme Court Registry and thereafter, the Supreme Court Registry undertakes steps to ensure service on the opposite party. In case the party upon which the document is required to be served is resident out of India, the provisions in the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 (“CPC”) are required to be followed. Order V Rule 26 CPC prescribes the way of service on parties residing out of India. Accordingly, service of Section 11 applications by the Supreme Court Registry would be in consonance with the provisions of CPC which is a long drawn and time-consuming process. Further, in case of Section 11 applications before the Supreme Court, the applicant in accordance with Rule 10 of the Scheme is required to deposit INR 15,000 with the Supreme Court for processing the application which includes costs of service.

Since service of Section 11 applications is only made upon notice and there is no stipulation for advance service on the opposite party, a considerable time elapses between the date on which the Court issues notice and service is affected on the opposite party. It is submitted that if the following amendments to the relevant SC Rules and Scheme are made, it may go a long way in ensuring quicker disposal of Section 11 applications:

- The applicant must serve a copy of the Section 11 application in advance to the opposite party. In non-contentious Section 11 applications, if the respondent(s) appears on the first date itself, the application may be finally decided on the same day. In fact, a few High Courts already have rules in place for advance service of Section 11 applications without which the application is not listed.

- In all applications on which notice is issued, the Supreme Court should allow dasti service including service by email on the opposite party in addition to the mode already prescribed under the SC Rules. Since Rule 2, Order LIII of the SC Rules allows service on the advocate-on-record of any party at his registered office or registered email address including that of his clerk, permitting dasti service by email in the first instance would not be a novel concept. Similarly, the applicant should be allowed to post/courier/email the complete copy of the application directly to the address of the respondent(s) stated in the memo of parties. This is likely to ensure that service is affected in a shorter time. Under appropriate circumstances, service by email alone may also be considered sufficient service.

- To ensure appearance of the opposite party, the notice should specifically state that notice by the applicant shall be deemed to be sufficient service. The applicant may also be required to file proof of delivery and upon such filing, the application should be listed before the Court. An even quicker way to ensure disposal of Section 11 applications would be if the order issuing notice states a returnable date i.e. the date on which the Section 11 application would next be listed. This would help bypass the deficiency in computer based software system which otherwise lists Section 11 applications in due course.

The above-suggested amendments to the SC Rules and the Scheme will go a long way in furthering the object of the Act.

Listing of Section 11 applications after completion of pleadings

At present, Section 11 applications get listed before the Roster Bench after completion of pleadings before the Registrar in due course, on a date determined by the computer based software. As such, the software does not list Section 11 applications expeditiously and in preference to other categories of cases pending before the Supreme Court.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to modify/update the software to ensure that Section 11 applications are listed before the Roster Bench immediately upon completion of pleadings and preferably within two weeks to ensure the Court has sufficient time to hear the application. It is essential to treat Section 11 applications as a separate category at all stages – at the time of filing, for the purposes of services and for the purpose of listing for final disposal.

One other way to ensure quicker disposal of Section 11 applications would be by amending the SC Rules to allow the Registrar to pass an order after completion of pleadings to list Section 11 applications within two weeks before the Court.

These measures, if employed will further the object of the Act, and give effect to the objective which the Legislature intended to achieve through the relevant amendments contained in the 2015 and 2019 Amendment Acts.

C. Reverting to the earlier practice of listing Section 11 applications before a Single Judge

Section 11 of the Act read with Rule 3 of the Scheme allows the Chief Justice to designate any person or institution for the purpose of appointing an arbitrator. Until recently, Section 11 applications were decided by a Single Judge designated by the Chief Justice in accordance with the provisions of the Scheme and in exercise of powers under the Act. This ensured quicker disposal of Section 11 applications since the Single Judge would hear these applications periodically. Moreover, a designated Judge hearing Section 11 applications on designated days ensures that all such applications are heard since no other matters would be on this list. Therefore, it may be better to revert to the practice of designating a Single Judge to deal with Section 11 applications.

III. Changes sought to be brought by the 2019 Amendment Act

As stated above, the 2019 Amendment Act seeks to substantially alter the regime when the parties fail to appoint arbitrators themselves and seek intervention in this regard. Section 11, as amended by the 2019 Amendment Act, now places this responsibility on an arbitral institution to be designated by the Supreme Court on the basis of a gradation to be carried out by the ACI.

Since the ACI has not been established as yet, the manner of appointment of arbitrator under Section 11 continues to remain unchanged. However, even with the establishment of the ACI, the 2019 Amendment Act does not specify the rules or procedures to be followed by the arbitral institutions in making appointments pursuant to Section 11.

For instance, there are no rules or express provisions on the scope of the arbitral institution’s role in the appointment of the arbitrator and whether any inquiry is required to be carried out by an arbitral institution tasked with the responsibility of implementing Section 11. In this regard, the courts have, through various judgments, interpreted the scope of determination that is required to be carried out by them in Section 11 applications. It is unlikely that an arbitral institution would carry out the level of analysis that the courts have undertaken in Section 11 applications. The amendments to Section 11, however, support the conclusion that the arbitral institution will likely only be expected to appoint the arbitrator, without any determination on whether an arbitrator ought to be appointed or not, such determination being left to the arbitrator in terms of Section 16 of the Act. This is buttressed by Section 3(5) of the 2019 Amendment Act, which deletes sub-sections (6-A) and 7 of Section 11.

The amendments also do not specify any procedural requirements that are to be followed while filing Section 11 applications. When the contracting parties agree to have their arbitrations administered by any arbitral institution, they agree to all the procedural rules prescribed by the institution, including with respect to the form of pleadings and mode of service. However, in the case of a Section 11 application, the parties are only approaching the institution for the purpose of the appointment of the arbitrator (and only because this is the institution designated by the Supreme Court). The arbitration itself will continue to remain ad hoc. Given this, it is likely that separate rules will be framed for the purpose of filing Section 11 applications under the Act. Section 43-L of the Act also prescribes that the ACI may, in consultation with the Central Government, make regulations for the discharge of its functions under the Act.

It is hoped that any rules framed in relation to Section 11 applications, whether by the ACI or otherwise, will ensure that the procedural lapses/delays analysed in this article are done away with. Arbitral institutional rules typically provide greater flexibility, whether in the mode of filing, the form of filing or the mode of service, than court rules permit. For instance, most arbitral institution rules permit service of documents by several modes such as courier, speed post, or email (ref., as an example, Rule 2.1 of the MCIA Rules, 2016). Any rules to be framed with respect to Section 11 should retain the flexibility that arbitrations typically offer.

Pertinently, the 2019 Amendment Act also obligates the arbitral institution to dispose of the Section 11 application within a period of 30 days from the date of service of notice on the opposite party. The amended sub-section (13), as it is currently worded, makes this timeline mandatory and not merely directory. It is hoped that this timeline is followed in the future to further the object of the Act and the amendments brought about by the legislature.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is submitted that until the relevant sections of the 2019 Amendment Act are notified, the mantle of ensuring quicker disposal of Section 11 applications continues to be held by the Supreme Court. While it may seem that it is too late in the day to undertake any structural changes, the Supreme Court could set an example for the courts below by adapting and adopting mechanisms which promote a more efficient justice delivery system. To make India a more arbitration-friendly jurisdiction, the changes such as the ones suggested above could be adopted, especially since commercial disputes resolution by arbitration has over the last few decades become a more preferred means of dispute resolution, a preference escalated due to the pandemic. Section 11 applications are filed to kickstart arbitral proceedings and therefore any and all measures should be taken by the Supreme Court to ensure that appointment of the arbitral tribunal is completed in the least possible time once the parties appear before it.

**Advocate

[1] The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

[2] This article only focusses on the role of the Supreme Court in the appointment of arbitrators under Section 11 of the Act and therefore references are restricted to that extent.

[3] The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015

[4] The Supreme Court Rules, 2013

[5] The Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019

[6] The data was gathered from https://main.sci.gov.in/case-status on July 8, 2020.

[7] The data for six Section 11 applications filed in 2017 was not available on the Supreme Court’s website as on July 8, 2020.

[8] Ibid.