Although thousands of litigants knock the doors of the Supreme Court of India annually, in their quest for justice, statistics reveal that the most widely used (or abused) route is the extraordinary jurisdiction vested in the Court under Article 136 of the Constitution, and cases filed thereunder are colloquially referred to as special leave (to appeal) petitions. This jurisdiction is plenary in nature and empowers the Court to grant leave to appeal against a determination of any court or tribunal.

Contemporaneous data suggests that almost 92% of the cases filed in the Supreme Court are special leave petitions. That then begs the question — How are they really special? Are they special because the Supreme Court prioritises them over everything else? The simple answer is that Article 136 of the Constitution states that the Supreme Court may grant leave to certain appeals, which would otherwise not be permitted to be in the Supreme Court, to be heard. If this is special, surely there must be other ordinary avenues to appeal to the Supreme Court. The Constitution has dealt with these under Articles 132 to 134-A. Although the plain phraseology of Article 136 is clearly distinct from Articles 132 to 134-A which contemplate an appeal in civil, criminal cases or on a certificate granted by the High Court, the common thread that runs through this family of provisions found in Chapter IV of the Constitution which deals with the Union Judiciary, including Article 136 is that the petition must raise a question of law requiring interpretation by the highest court of the land.

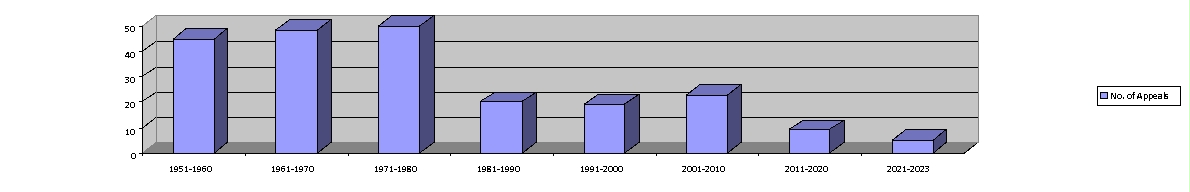

If 92% of the 60,000 cases filed annually in the Supreme Court are special leave petitions (SLPs), can you guess how many are ordinary appeals? Well, here is the data on how many appeals (other than SLPs) have been decided in the history of the Supreme Court:

Why is it that appeals under Articles 132 to 134-A pale into virtual oblivion in comparison with SLPs under Article 136? Possibly owing to a slew of factors,

- The SLP route provides easier access to the Supreme Court. In recent years this jurisdiction has been increasingly resorted to as a regular appellate provision and more often than not, the Supreme Court is invited to reappreciate questions of fact as opposed to determining questions of law. In fact, almost everyone who can afford a lawyer in the Supreme Court will chance an SLP against an order of the High Court or a tribunal1. It does not really matter what the issue is or the issue involved: evicted tenant wanting to remain in the premises for a bit longer, convict on parole wanting to stay out of jail for few more days, bail pending trial, husband wanting reduction of the measly sum of interim maintenance to his wife pending divorce, the list goes on. A review of about 1000 judgments delivered every year by the Supreme Court, revealed that a vast majority of them do not decide a substantial question of law2. Although Article 136, if read on its own and in a pedantic manner, does contemplate the theoretical possibility of the Supreme Court hearing an appeal directly from an order of a Munsif, in practice, such an eventuality seems remote.

-

To come to the Supreme Court through the specific constitutional provisions relating to appeal (Articles 132-134) is a far more exacting and onerous exercise because the High Court needs to certify that the case raises a substantial question of law that requires a decision of the Supreme Court. This route requires the lawyer for the losing side to argue for a certificate to appeal and in that process, help the court frame the substantial question of law. The High Court would then, if it deemed it fit to do so, formulate the question and certify the case fit for appeal to the Supreme Court. The parties would have 60 days (not 90 as in the case of the SLP) to file the appeal.

Chapter IV once again underlines the prescience of the framers of the Constitution. An examination of Articles 132-134, reveals how Article 136 fits into the scheme. Arguably the Constitution intended appeals to the Supreme Court to be controlled by the High Courts as a rule, with the SLP route being an exception. In other words, the High Court acts as a filter to ensure that only meritorious cases, namely, those which involve issues where there is uncertainty in the law are presented to the Supreme Court. SLP was perhaps meant to be sparingly used and only after the High Court failed to certify the case as being fit for appeal. Perhaps those who imagined the Constitution did expect the number of SLPs to be a huge multiple of appeals. They perhaps thought that the SLPs would not be many more than the number of appeals. Imagine if we could manage that, there would be no cases pending in the Supreme Court for more than one year. Seems almost magical, doesn’t it?

So, when and why did this finely structured mechanism start to unravel? One is not sure but some time in the 1980s when the Supreme Court decided that it was a “people’s court” in terms of being more accessible especially in respect of issues pertaining to a violation of rights under Part III, the approach to SLPs also became more liberal. Lawyers were disincentivised to use the “certificate route” where there was a clear filter. As a result, SLPs constitute an overwhelming majority of the approximately 60,000 cases filed every year in the Supreme Court. A vast majority of these do not require the intervention of the Supreme Court since they do not raise a question of law that is res integra. The Supreme Court is not really a people’s court — too many cases that do not deserve to be heard, clog up the system so that the cases that the Supreme Court should be hearing just do not get heard at all, or at best, many years later3.

How does the Supreme Court unclog the system? Many scholars and think tanks have suggested (i) more Judges and courts by having regional benches; (ii) national appeals court for all appeals liberating time thereby enabling the Supreme Court to perform its primordial function as the constitutional court; and (iii) more rigorous filtering of petitions and more focused and brief hearings like the US Supreme Court.

The first two will require amendments to the law and the third will require a compact between the Bar and the Bench which seems very unlikely to be reached for a variety of reasons. There is no incentive for lawyers to filter out cases and it is impossible to predict, given how the Supreme Court works, to be sure that a particular case lacks merit. Lawyers know, from experience, that almost every case has a fair chance of being admitted by the Supreme Court. Unless the Supreme Court itself imposes restrictions on the kinds of cases it hears, limits appeals to Articles 132-134 and allows SLPs only in exceptional cases when the High Court has erred in denying a certificate to appeal, SLPs will clog the Supreme Court for the foreseeable future.

While this may seem radical, it is not. This is what the Constitution envisioned. This is the procedure followed in the UK and the United States. The pendency in the Supreme Court could drastically reduce if we worked the Constitution as it was envisaged. It is not a radical idea. It is really a very conservative one based on a plain reading of the Constitution.

*Advocate and English Solicitor.

**Advocate-on-Record, Supreme Court of India.

The Authors acknowledge the work of Deeksha Dabas, Editorial Assistant; Apoorva Goel , Editorial Assistant; and Bhumika Indulia

1. See, Aparna Chandra, et al., Court on Trial (Penguin, 2023).

2. See, Aparna Chandra, et al., Court on Trial (Penguin, 2023).

3. See, Annual report of the Supreme Court of India , Available at: https://main.sci.gov.in/pdf/AnnualReports/INDIAN%20JUDICIARY%20Annual%20Report%202021-22.pdf