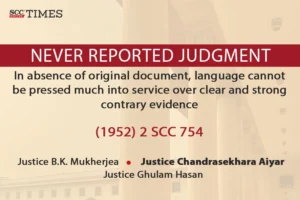

Supreme Court: In an appeal filed by the appellants, the three-judges bench of B.K. Mukherjea, Chandrasekhara Aiyar* and Ghulam Hasan, JJ., observed that the stress was laid by the respondents on the use of the words ‘him or his order’ in the promissory note, and it was argued that the language employed in the promissory note indicated an individual. The Supreme Court opined that the language used in a document, particularly in absence of originals, one was not able to say whether the translations were strictly correct or rather loose. The language could not be pressed much into service in face of the clear and strong evidence to the contrary. Thus, the Supreme Court disagreeing with the Allahabad High Court (‘the High Court’), opined that the appellant was entitled to sue for the recovery of the alleged due amount, as the promissory notes were executed in the Kshetra’s favour and not any individual.

Background

In the present case, Baba Kali Kamliwaley Panchaiti Kshetra, Rishikesh, the appellant was a charitable society registered under the Societies Registration,1860. The appellant filed a suit against the respondents, Lala Lachmi Chand and Onkar Prasad, for recovery of Rs 15,368-11-0 with interest and costs, said to be due on a loan advanced to Lala Lachmi Chand on 25-8-1928 and evidenced by the execution of promissory notes from time to time.

The respondents stated that the appellant was not the payee under the original promissory note of 25-08-1928, which was the basis of the claim, and thus was legally barred from suing based on the said promissory note. Accordingly, five issues were framed, and the first was that the appellant was legally debarred from suing based on the promissory note, dated 25-8-1928.

The Trial Court decided all the issues in the appellant’s favour and gave the Kshetra a decree for the amount claimed with costs and pending and future interest at 3% per annum. However, an appeal was filed to the High Court, wherein it was held that the payee was not the institution, but an individual, thus the appellant was legally barred from suing based on the promissory note.

Thus, the appellant filed the present appeal.

Analysis, Law, and Decision

The Supreme Court agreed with the appellant’s contention and noted that under the promissory note of 25-08-1928, the payee was mentioned as Shri 108 Baba Kali Kamliwaley Ram Nath Manni Ramji of Rishikesh, and it was not disputed that Ramnath who the disciple of the founder, Kali Kamliwaley, died in 1926. The Supreme Court opined that addition of his name and Manni Ramji to Shri 108 Baba Kali indicated that the reference was to the institution and not to any individual. Further, if Ramnathji, an individual, was the payee under the promissory note, the Supreme Court opined that it was faced with absurdity that it was executed in favour of a man who died 13 years before.

The Supreme Court noted the respondents’ reply to the appellant’s notice prior to the suit, wherein the first respondent acknowledged the Kshetra’s right to recover the amount and requested that as he was unable to pay the amount in one lump sum, it might be realised from him in instalments. The Supreme Court opined that it appeared form this documents that the demand was made on behalf of Shri 108 Baba Kali Kamliwaley Ramnathji, Rishikesh which obviously meant the institution.

Further the Supreme Court observed that the stress was laid by the respondents on the use of the words ‘him or his order’ in the promissory note, and it was argued that the language employed indicated an individual. The Supreme Court opined that the language used in a document, particularly in absence of originals, one was not able to say whether the translations were strictly correct or rather loose. The language could not be pressed much into service in face of the clear and strong evidence to the contrary. Further, regarding the respondents’ contention that why the promissory notes were not taken in the name under which the Kshetra society was registered, the Supreme Court opined that the people responsible adhered to the older appellation of mentioning the guru’s names and disciples as more appropriate to its religious and charitable character.

Thus, the Supreme Court disagreeing with the High Court, opined that the appellant was entitled to sue for the recovery of the alleged due amount, as the promissory notes were executed in the Kshetra’s favour and not any individual. The Supreme Court further opined that as there were other issues which had been left undecided, the matter had to go back to the High Court for decision and the respondents would pay the appellants costs that had incurred so far.

[Baba Kali Wala Panchaiti Kshetra, Rishikesh v. Onkar Prasad, (1952) 2 SCC 754, decided on 17-12-1952]

*Note: Interpretation of deeds and documents

In case of interpretation of deeds and documents, to ascertain the intention of the parties, the document must be considered as a while. Generally, the words employed in a deed/document should be construed in its ordinary sense, unless there were indications to do otherwise. In Sant Ram v. Rajinder Lal, (1979) 2 SCC 274, it was held that two rules must be remembered while interpreting deeds and statutes. Firstly, in drafting it was not enough to gain a degree of precision which a person reading in good faith could understand, but it was necessary that a person reading in bad faith could not misunderstand. Secondly, so long as law was at the service of life, it could be divorced from the social setting. Thus, whenever there was a doubt regarding the interpretation, recall the face of the poorest and the weakest man and ask, if the step you contemplate was going to be of any use to him.

*Judgment authored by- Justice Chandrasekhara Aiyar

Advocates who appeared in this case :

For the Appellant: S.P. Sinha, Senior Advocate (Krishna Behari Lal Aggarwal, Advocate, with him);

For the Respondent: Rang Behari Lal, Senior Advocate (Harnam Das, Advocate, with him)