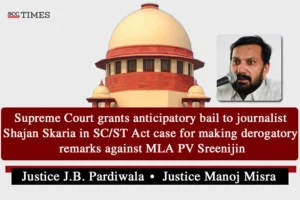

Supreme Court: In an appeal against the judgment and order passed by the Kerala High Court, wherein the High Court affirmed the order passed by the Special Judge, declining to grant anticipatory bail to Journalist Shajan Skaria for the offence punishable under Sections 3(1)(r) and 3(1)(u) respectively of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (‘Act, 1989’), the division bench of J.B. Pardiwala* and Manoj Misra, JJ. while setting aside the impugned order, granted anticipatory bail to Shajan Skaria.

Background:

The accused is an Editor of an online news channel named “Marunandan Malayali”. In 2023, he published a video on YouTube, levelling certain allegations against the PV Sreenijin, who is a Member of the Kerala Legislative Assembly representing the Kunnathunad constituency, a seat reserved for the members of the Scheduled Castes. He complained that the video was published by the accused in order to publicise, abuse and insult the complainant, who is a member of a Scheduled Caste. Thus, an FIR was registered against Shajan Skaria and two other persons, who are not parties to the present appeal, for offences punishable under Section 120(o) of the Kerala Police Act (‘KP Act’) and Sections 3(1)(r) and 3(1)(u) respectively of the Act, 1989. The complainant alleged that the video has caused him a lot of humiliation, mental pain and agony. The complainant has also alleged that the video was uploaded with the intention to humiliate and ridicule him among the public with the knowledge that the complainant is a member of the Pulaya community, which is a Scheduled Caste.

Apprehending his arrest, the Shajan Skaria went before the Court of Special Judge praying for grant of anticipatory bail under Section 438 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 (‘CrPC’). The Special Judge, vide order rejected the anticipatory bail application, holding that the allegations in the FIR are prima facie sufficient to attract the offence under the Act, 1989 and the bar of Section 18 of the said Act prohibits the Court from exercising powers under Section 438 of the CrPC. Aggrieved, Shajan Skaria challenged the order passed by the Special Judge before the Kerala High Court of Kerala, wherein the High Court refused to grant anticipatory bail to him. Thus, the present appeal was filed.

Issues, Analysis and Decision:

1. Whether Section 18 of the Act, 1989 imposes an absolute bar on the grant of anticipatory bail in cases registered under the said Act?

The Court examined the evolution of the concept of anticipatory bail.

After noting the statement of objects and reasons accompanying the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Bill, 1989, the Court said that he purpose of the Act, 1989 is to prevent the commission of offences of atrocities against the members of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, to provide for establishment of special courts for the trial of such offences and to make provisions for the relief and rehabilitation of the victims of such offences.

The Court also took note of Section 18 of the Act, 1989 which makes the remedy of anticipatory bail unavailable in cases falling under the Act, 1989. The Court said that the legislature in its wisdom thought fit that the benefit of anticipatory bail should not be made available to the accused in respect of offences under the Act, 1989, having regard to the prevailing social conditions which give rise to such offences and the apprehension that the perpetrators of such atrocities are likely to threaten and intimidate the victims and prevent or obstruct them in the prosecution of such offences, if they are allowed to avail the benefit of anticipatory bail.

The Court referred to State of Madhya Pradesh v. Ram Krishna Balothia, (1995) 3 SCC 221, wherein it was held that although Article 21 protects the life and personal liberty of every person in this country, which also includes the right to live with dignity, yet it cannot be said that Section 438 of the CrPC is an integral part of Article 21. Thus, the non-application of Section 438 to a certain distinct category of offences cannot be considered as violative of Article 21 of the Constitution.

The Court noted that over a period, the courts across the country started taking notice of the fact that the complaints were being lodged under the Act, 1989 out of personal and political vendetta. To overcome the bar of Section 18 of the Act, 1989, the persons against whom such complaints were being lodged started invoking the writ jurisdiction of the High Court under Article 226 of the Constitution. Thereafter, Parliament amended the Act, 1989 vide the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2018, inserting Section 18-A. While upholding the validity of Section 18-A of the Act, 19891, this Court observed that if the complaint does not make out a prima facie case for applicability of the provisions of the Act, 1989 then the bar created by Sections 18 and 18-A(i) shall not apply and thus the court would not be precluded from granting pre-arrest bail to the accused persons.

Concerning the significance of the expression “arrest of any person” appearing in Section 18 of the Act, 1989, the Court said that Section 18 bars the remedy of anticipatory bail only in those cases where a valid arrest of the accused person can be made as per Section 41 read with Section 60A of CrPC. Thus, an arrest can be effected if there is a reasonable complaint, credible information or reasonable suspicion and the police officer has a reason to believe that such offence has been committed by the accused person and the arrest is necessary

The Court said that t the term ‘arrest’ appearing in the text of Section 18 of the Act, 1989 should be construed and understood in the larger context of the powers of police to effect an arrest and the restrictions imposed by the statute and the courts on the exercise of such power.

Thus, the Court held that the bar under Section 18 of the Act, 1989 would apply only to those cases where prima facie materials exist pointing towards the commission of an offence under the Act, 1989.

2. When can it be said that a prima facie case is made out in a given FIR/complaint?

The Court said that the expression “where no prima facie materials exist warranting arrest in a complaint or FIR” should be understood as “when based on first impression, no offence is made out as shown in the FIR or the complaint”. Thus, if the necessary ingredients to constitute the offence under the Act, 1989 are not disclosed on the prima facie reading of the allegations levelled in the complaint or FIR, then in such circumstances, as per the consistent exposition by various decisions of this Court, the bar of Section 18 would not apply and the courts would not be absolutely precluded from granting pre-arrest bail to the accused persons.

The Court opined that in each case, an accused may argue that although the allegations levelled in the FIR or the complaint do disclose the commission of an offence under the Act, 1989, yet the FIR or the complaint being palpably false on account of political or private vendetta, the court should consider the plea for grant of anticipatory bail despite the specific bar of Section 18 of the Act, 1989. However, if the accused puts forward the case of malicious prosecution on account of political or private vendetta then the same can be considered only by the High Court in exercise of its inherent powers under Section 482 of the Code or in exercise of its extraordinary jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution. However, powers under Section 438 of the CrPC cannot be exercised once the contents of the complaint/FIR disclose a prima facie case.

The Court said that there is the duty of the Courts to determine prima facie existence of the case, to ensure that no unnecessary humiliation is caused to the accused. The Courts should not shy away from conducting a preliminary inquiry to determine if the narration of facts in the complaint/FIR in fact discloses the essential ingredients required to constitute an offence under the Act, 1989. The Courts should apply their judicial mind to determine whether the allegations levelled in the complaint, on a plain reading, satisfy the ingredients constituting the alleged offence.

The Court stated that the minimum threshold for determining whether an offence under the Act has been committed or not is to ascertain whether all the ingredients which are necessary to constitute the offence are prima facie disclosed in the complaint or not. An accusation which does not disclose the necessary ingredients of the offence on a prima facie reading cannot be said to be sufficient to bring into operation the bar envisaged by Section 18 of the Act, 1989. Holding otherwise would mean that even a plain accusation, devoid of the essential ingredients required for constituting the offence, would be enough for invoking the bar under Section 18.

3. Whether the averments in the FIR/complaint in question disclose commission of any offence under Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989?

The Court noted the basic ingredients to constitute the offence under Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989 and said that Shajan Skaria was alleged to have published a video on YouTube, containing a slew of reckless statements in the form of allegations levelled against the complainant. The Court without looking into the veracity or the truthfulness of such allegations as contained in the video, tried to understand that even if all the statements alleged to have been made are believed to be true, whether any offence under Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989 could be said to have been prima facie committed.

The Court opined that all insults or intimidations to a member of the Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe will not amount to an offence under the Act, 1989 unless such insult or intimidation is on the ground that the victim belongs to Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe.

The Court noted that there is nothing in the uploaded video transcript to indicate even prime facie that those allegations were made by Shajan Skaria only because the complainant belongs to a Scheduled Caste.

After relying on Hitesh Verma v. State of Uttarakhand, (2020) 10 SCC 710, the Court said that the offence under Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989 is not established merely on the fact that the complainant is a member of a Scheduled Caste or a Scheduled Tribe, unless there is an intention to humiliate such a member for the reason that he belongs to such community.

The Court said that it is not the purport of the Act, 1989 that every act of intentional insult or intimidation meted by a person who is not a member of a SC or ST to a person who belongs to a SC or ST would attract Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989 merely because it is committed against a person who happens to be a member of a SC or ST. On the contrary, Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989 is attracted where the reason for the intentional insult or intimidation is that the person who is subjected to it belongs to SC or ST.

The Court highlighted that the words “with intent to humiliate” as they appear in the text of Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989 are inextricably linked to the caste identity of the person who is subjected to intentional insult or intimidation. Not every intentional insult or intimidation of a member of a SC/ST community will result into a feeling of caste-based humiliation.

4. Whether any offence under Section 3(1)(u) of the Act, 1989 could be said to have been prima facie made out in the FIR/complaint in question?

The Court took note of the basic ingredients for constituting an offence under Section 3(1)(u) of the Act, 1989, and opined that there is nothing to even prima facie to indicate that Shajan Skaria by publishing the video on YouTube promoted or attempted to promote feelings of enmity, hatred or ill-will against the members of Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes. The video has nothing to do in general with the members of Scheduled Caste or the Scheduled Tribe. His target was just the complainant alone. The offence under Section 3(1)(u) will come into play only when any person is trying to promote ill feeling or enmity against the members of the scheduled castes or scheduled tribes as a group and not as individuals.

5. Whether mere knowledge of the caste identity of the complainant is sufficient to attract the offence under Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989?

The Court held that mere knowledge of the fact that the victim is a member of the Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe is not sufficient to attract Section 3(1)(r) of the Act, 1989.

CASE DETAILS

|

Citation: Appellants : Respondents : |

Advocates who appeared in this case For Petitioner(s): For Respondent(s): |

CORAM :

1. Prathvi Raj Chauhan v. Union of India, (2020) 4 SCC 727