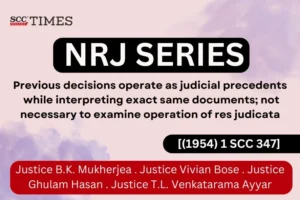

Supreme Court: In an appeal filed against the judgment and decree dated 16-5-1949 of the Patna High Court (‘the High Court’), the four-Judges Bench of B.K. Mukherjea, Vivian Bose*, Ghulam Hasan and T.L. Venkatarama Ayyar, JJ., stated that the question that whether Taluka Kakwara was a government ghatwali or a zamindari fell for consideration in Thakur Rudreshwari Prasad v. Rani Probhabati, 1951 SCC 1031 (‘Thakur Rudreshwari case’). Regarding the appellant’s contention that the previous decision was not res judicata, the Supreme Court stated that it was not necessary to examine the res judicata issue because even if the matter was not concluded, the previous decision would operate as a judicial precedent on the interpretation of these very documents.

The Supreme Court stated that all the contentions raised by the appellants were equivocal. They did not, either separately, or taken as a whole, detract from the soundness of the previous decision. The Supreme Court further stated that in any case, the fresh matter, which was placed before them, did not justify reconsideration of the earlier decision and accordingly dismissed the present appeal.

Background

In the present case, the appeal arose out of a suit on a mortgage dated 9-4-1929 executed by Appellant 1 for a sum of Rs. 1,10,000. The other appellants were after-born sons of Appellant 1. They had no present interest in the mortgaged property and were only impleaded so that a personal decree could be passed against them as well in the event of the mortgaged property being insufficient to satisfy the plaintiffs’ claim.

The main defence was that the mortgaged properties, namely, ‘Taluka Kakwara’ and ‘Taluka Dudhari’, were government ghatwalis and were inalienable. Thus, the mortgage was void and inoperative. The first court rejected this contention and held that the two talukas were zamindari ghatwalis and not government and that they were alienable with the zamindars’ consent.

On appeal to the High Court, Appellant 1’s contention about Dudhari was not seriously pressed and it was not touched at all in this Court. The High Court dismissed the appeal and upheld the Trial Court’s decision on both points.

Analysis, Law, and Decision

The Supreme Court stated that the question that whether Taluka Kakwara was a government ghatwali or a zamindari was the very question which fell for consideration in Thakur Rudreshwari case (supra). The only difference was that in Thakur Rudreshwari case (supra), the matter arose in execution whereas in the present case, it arose in the suit itself. In Thakur Rudreshwari case (supra), the present respondents obtained a simple money decree against Appellant 1 and in execution brought Taluka Kakwara to sale. In the present case, the respondents filed the case on the mortgage. In both cases, the defence about Taluka Kakwara was the same.

The Supreme Court observed that Appellant 1’s title was derived from two sanads. The first was granted by one Captain Browne to the appellant’s ancestors in 1776. The second was granted by one Zamindar Raja Kadir Ali to the same persons in 1780. The question was whether Captain Browne acted on the Zamindar’s behalf when he made his grant and whether the Zamindar acted on his own accord or whether both acted as agents of the then ruling power. The Supreme Court stated that this question was elaborately discussed in Thakur Rudreshwari case (supra) and the conclusion reached was that Captain Browne acted on behalf of the Zamindar and that Raja Kadir Ali acted as the zamindar. It was held that both grants were on behalf of the zamindar and that the second was in confirmation of the first.

Regarding the appellant’s contention that the previous decision was not res judicata, the Supreme Court stated that it was not necessary to examine the res judicata issue because even if the matter was not concluded, the previous decision would operate as a judicial precedent on the interpretation of these very documents. The root of title was the same and the evidence and circumstances was also identical. The Supreme Court stated that nothing new had been produced in the present case. Thus, the Supreme Court did not allow the appellants to re-argue the case and asked to confine himself to matters which were not considered and dealt with in the previous judgment.

The Supreme Court stated that all these contentions were equivocal. They did not, either separately, or taken as a whole, detract from the soundness of the previous decision. One of the strongest points made against the appellants was that the right of appointment and dismissal lay with Raja Kadir Ali. The Supreme Court opined that it was almost conclusive to show that the grant was of a zamindari ghatwali. The Supreme Court further stated that in any case, the fresh matter, which was placed before them, did not justify reconsideration of the earlier decision and accordingly dismissed the present appeal.

[Thakur Rudreshwari Prasad Sinha v. Ramabati Devi, (1954) 1 SCC 347, decided on 10-03-1954]

*Judgment authored by: Justice Vivian Bose

Advocates who appeared in this case :

For the Appellants: L.M. Ghose, Senior Advocate (I.N. Shroff, Advocate, with him);

For the Respondents: B.C. De, Senior Advocate (S.P. Varma, Advocates, with him).

Note: Res Judicata and Judicial Precedents

Section 11 of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908 provides the doctrine of res judicata. As per the provision, no court will have the power to try any fresh suit or issues which has been already settled in the former suit between the same parties. Further, the court will also not try the suits and issue between those parties under whom the same parties are litigating under the same title and matter has been already adjudicated by the competent court.

In All India Reporter Karamchari Sangh v. All India Reporter Ltd., 1988 Supp SCC 472, the Supreme Court has held that: “Article 141 of the Constitution provides that the law declared by Supreme Court shall be binding on all courts within the territory of India. Even apart from Article 141 of the Constitution the decisions of the Supreme Court, which is a court of record, constitute a source of law as they are the judicial precedents of the highest court of the land. They are binding on all the courts throughout India. Similarly, the decisions of every High Court being judicial precedents are binding on all courts situated in the territory over which the High Court exercises jurisdiction. Those decisions also carry persuasive value before courts which are not situated within its territory. The decisions of the Supreme Court and of the High Courts are almost as important as statutes, rules and regulations passed by the competent legislatures and other bodies since they affect the public generally.”