Introduction

Commercial matters often involve the question of costs i.e. which party is entitled to how much recovery. Today we have two extreme positions, one which is referred to as the loser pays rule (prominent in the United Kingdom) and the other extreme lies in the American rule where litigant bears their own costs. This piece analyses these two rules using a law and economic lens in an attempt to understand which rule encourages meritorious claims and discourages frivolous litigation. It also attempts to understand the Indian framework of costs and which rules will fit best into the Indian framework.

Section I of this piece introduces the English and American rules for cost-shifting. Section II delves into the theoretical undergrounds for both these rules. Indian framework is discussed in Section III. Both the abovementioned rules are then analysed from a law and economic lens in Section IV and further critical analysis is done in Section V along with the suitability of rules in the Indian context.

Cost-shifting rules

The cost incurred by the party in a suit is a major factor in determining whether a dispute will result in litigation. In civil and commercial matters, money plays a significant role. The financial burden of litigation may be the single most important factor in deciding whether to fight in court.

Lawyers often think about cost and fee allocation in quasi-Shakespearean terms: “To shift or not to shift?”.1 The cost-shifting rules can be broadly divided into two systems. On the one hand, lies the “English rule” which entails shifting winner litigation costs to the loser (“costs follow the event”). On the other hand, lies the “American rule” which entails that each side bears its own cost. No system makes the winner completely whole (although some come very close), and even in the United States, some costs are shifted to the loser (although usually only a very small part); most jurisdictions operate somewhere in between.2

The following section will analyse the theoretical justification provided by the scholars to justify the abovementioned rules.

Theoretical reasons for English and American rule

The English rule (Loser Pays) appears to have its origins in the thirteenth century when the Statute of Gloucester 12753 gave plaintiffs a right to certain costs in specified real property actions. The principle was gradually extended over the centuries until in modern times it applies generally to all litigation subject to some exceptions.

The rationale behind this rule can be understood from the perspective of the defendant or plaintiff. From the defendant’s perspective, it seems unfair to have to pay the legal costs incurred in defending an unjustified claim or unwarranted attack that is thrown out by the court. On the other hand, if the plaintiffs have a good claim against another party who refuses to pay up when he or she should do so, the legal costs of being compelled to sue or enforce their rights should be borne by the defendant.4 This is closely connected to the idea of fairness.5

There is also an instrumental justification for the “loser pays” rule. To understand a distinction needs to be made between discouragement of non-meritorious, and encouragement of meritorious, litigation.6 The loser pays principle is seen as a means to discourage non-meritorious claims. The underlying logic seems simple enough: since the loser will pay twice (i.e. his or her own as well as the opponent’s costs), someone with a dubious claim will also think twice before taking it to court.

On the other hand, scholars have often found it hard to justify the American rule. However, an analysis of American cases would suggest otherwise. The American rule has been said to have first appeared in a 1796 opinion of the Supreme Court, Arcambel v. Wiseman7, in which the Court held that counsel fees of the prevailing party in the lower court litigation cannot be awarded as damages. Initially, it can be traced from debt law. Justice Rogers, writing for the court, said that the surety could recover the standard costs but noted “it would be going further than good policy requires” to recover counsel’s fees because “that would put it in the power of the surety” to “indulge an appetite for litigation at the principal’s expense”. In such an event, there would no longer be a “difference between an implied contract and an express contract of indemnity”.8

Further in one of the cases, the actual loss or injury did not exceed $10, but the jury rendered a verdict of $197.71.9 It was held that expenses were not the “natural and proximate consequence of the wrongful act”. And Ellsworth asked, rhetorically, “Who ever knew the plaintiff to prove his lawyer’s bills” or other such expenses related to the case in the court proceedings? The courts also pointed out the danger with the loser-pays principle. The Court reasoned that, because some attorneys demanded higher fees than others, there was a danger of abuse with attorneys charging higher fees than necessary.10

As per the courts, public policy requires that the honest plaintiff should not be frightened from asking for the aid of the law by fear of an extremely heavy bill of costs against him should he lose.11 But this does not apply to the plaintiff who seeks to harass, damage and even ruin the honest citizen by maliciously invoking the aid of the courts in support of a claim which he knows to be unfounded. In a patent-infringement case, the Chief Justice held that since litigation is at best uncertain one should not be penalised for merely defending or prosecuting a lawsuit lest the poor might be unjustly discouraged from instituting actions to vindicate their rights if the penalty for losing included the fees of their opponents’ counsel.12

Thus, English rule places more emphasis on reducing litigation by ensuring meritorious claims are given more impetus, on the other hand American rule places more emphasis on the “honesty” of the plaintiff so as to not deter litigation for fear of added costs pursuant to loss of the party. American rule should also be seen in a context where many litigations are against companies who have the wherewithal to hire expensive attorneys and imposing such costs on the plaintiff would seem to be unjustified.

However, the abovementioned claims merit further investigation which will be done in Section IV using the law and economics framework.

Analysis of the Indian Framework

Under the Code of Civil Procedure, 190813, and subject to such conditions and limitations as may be prescribed, “the costs of and incident to all suits shall be in the discretion of the Court, and the Court shall have full power to determine by whom or out of what property and to what extent such costs are to be paid, and to give all necessary directions for the purposes aforesaid”.14 It is expected that the wide discretion granted in the Code to courts to award costs should be exercised on legal principles, including those of reason and justice, and not capriciously.15

Also, quite importantly, the Code also mandates that “Where the Court directs that any costs shall not follow the event, the Court shall state its reasons in writing.”16 This indicates that the Code applies the English rule of cost shifting i.e. from winner to loser, and expects that this rule be followed except where the Court feels that there are reasons not to so shift. This means that the successful party is entitled to costs unless he is guilty of misconduct or there is some other good reason for not awarding costs to him.

However, the provisions of the Code set out above are honoured more in the breach than in the observance.17 The Supreme Court18 has lamented the fact that it has become a practice to direct parties to bear their own costs, despite the language of Section 35(2) of the Code. Further wherever costs are awarded. ordinarily the same are not realistic and are nominal. The costs have to be actual reasonable costs, including the cost of the time spent by the successful party, the transportation and lodging if any, or any other incidental cost besides the payment of the court fee, lawyer’s fee, typing and other costs in relation to the litigation. It is for the High Courts to examine these aspects.

As empowered by the Code of Civil Procedure19, (and exhorted by the Supreme Court) the High Courts of various States have made rules regulating their own procedure and the procedure of civil courts subject to their superintendence. It will be instructive to look at the rules of the Delhi High Court once.20

As per Chapter 11, Judgment and Decrees the general rule is that costs follow the event of the action; that is the costs of the successful party are to be paid by the party who is unsuccessful.21 Following rules provide with specific situations when costs may be disallowed. Some of the examples include when a party has without just cause resorted to litigation, where a party has raised an unsuccessful plea or answer to a plea (such as fraud limitation, minority, etc.) without sufficient grounds; In cases mentioned in Order 24 Rule 4, when a defendant deposits money in satisfaction of the claim, etc. The rules mention that wide discretion has been given to the court hence the list provided is an inclusive list and not an exhaustive list per se.

However, the list details only technical aspects when the English rule does not apply and fails to take into account the background realities of each party, such as the differential cost of litigation of parties, nature of claim, etc. Hence, this merits investigation into question, which rule should be applied by courts and when?

The following section will explore using the law and economic lens, which of the rules (English and American) should be adopted in civil litigation by the courts.

Law and economics analysis of the cost-shifting rules

The main aim of the cost-shifting rule is to encourage meritorious lawsuits and discourage frivolous lawsuits.22 For an economic analysis23 following variables are required:

p — Expected probability of success

A — Expected award

X — Cost of plaintiff’s legal fees

Y — Defendant’s legal fees

z — Expected net gain for the plaintiff

Under American rule, a plaintiff will decide to file a suit if his expected net gain would at least cover his own legal costs. The requirement is met when pA-X is greater than zero.

pA — X > 0 (American rule)

Under the English rule, a plaintiff will file suit if his expected net gain would be at least as large as his expected legal costs, which are equal to the total legal costs of both sides discounted by his probability of losing. The requirement is met when pA — (1-p)(X+Y) is greater than zero.

pA — (1 — p) (X + Y) > 0 (English rule)

To understand which of the above rules ensures our goal to encourage meritorious lawsuits and discourage frivolous lawsuits, it would be instructive for us to take an illustration.

Assuming that the cost of the plaintiff’s legal fees is Rs 10,000 represented as 10 (i.e. X = 10) and the same holds for the defendant (i.e. Y = 10) and the court awards Rs 15,000 represented as 15 (i.e. A = 15).

So, we have two equations with us

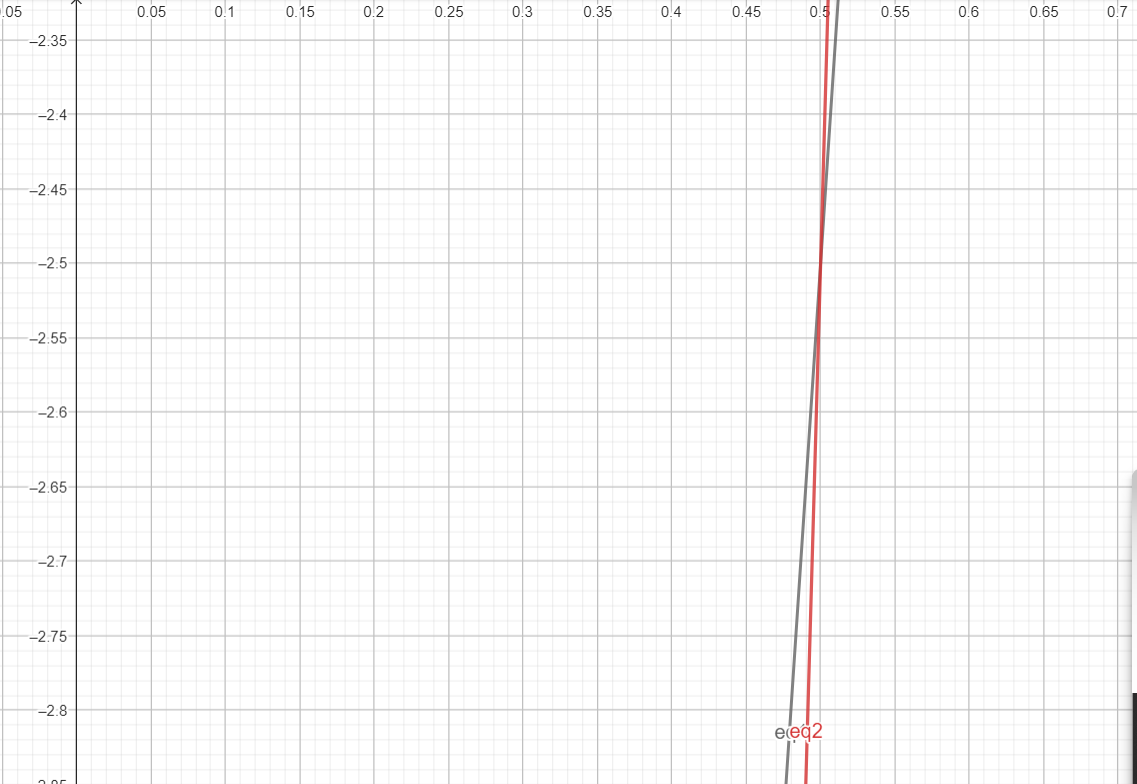

(eq1) 15p — 10 = z (American rule)

(eq2)15p — (1 — p) * 20 = z (English rule)

where z represents the expected net gain. Plotting the same on the graph will provide us with the following representation with x axis representing the expected probability of success and y axis representing the expected net gain.

Graph 1

From Graph 1, it will be observed that as the probability of success increases the expected net gain also increases in the case of both eq1 and eq2. However, at a point of probability say 0.7 on the x-axis, the expected net gain for the plaintiff will be higher in the case of eq2 i.e. under English rule as compared to American rule. Thus, in cases where the suit is clearly valid and the plaintiff is likely to win, he is more likely to file a suit under the English rule than under the American rule. Thus, English rule encourages meritorious suits as compared to American rule.

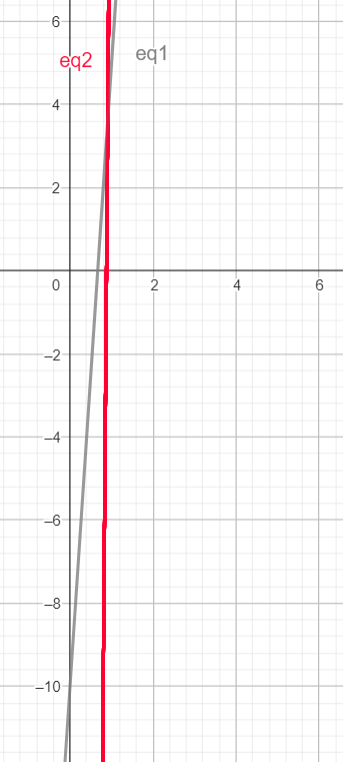

Graph 2

Now observe Graph 2. It will be observed that as the probability of success decreases the expected net gain also decreases in the case of both eq1 and eq2. However, at a point of probability say 0.4 on the x-axis, the expected net loss for the plaintiff will be higher in the case of eq2 i.e. under English rule as compared to American rule. Thus, in cases where the plaintiff is less likely to win, he is less likely to file a suit under the English rule than under the American rule. Thus, English rule discourages frivolous suits as compared to American rule.

The economic analysis seems to demonstrate the superiority of the English rule. Unlike the American rule, the English rule more effectively deters frivolous suits while encouraging meritorious suits.24 However, it is to be noted that the above analysis was done under various assumptions to reach the abovementioned conclusions. The next section will challenge these assumptions and show why the application of American rule is also important in certain cases.

Exception to loser-pays principle

From the analysis done in the previous section, it is not suggested that the court should blindly apply the English rule of transferring costs from loser to winner. As mentioned previously, American rule also has a good theoretical basis for its application. Hence, this section will attempt to give some illustrations using a law and economics lens when English rule might not be applied and American rule may be more suitable.

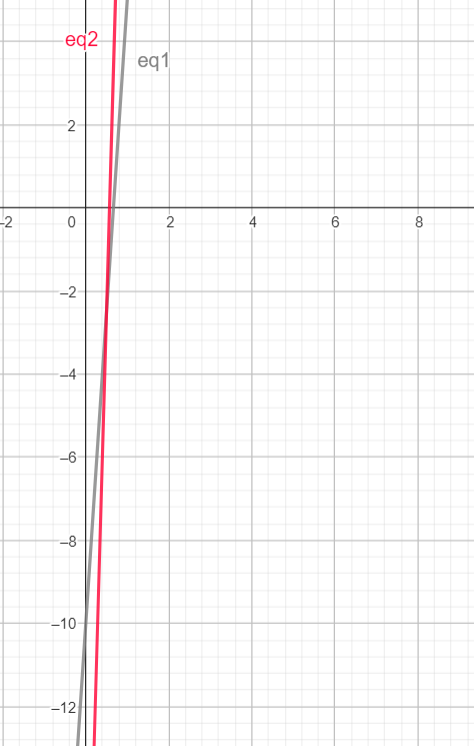

Case 1: When the defendant’s legal costs are extremely high as compared to the plaintiff’s legal costs

There can be a case when the defendant incurs a much higher cost for the services of the advocate as compared to the plaintiff. Assuming that the expected award be Rs 15,000 (represented as 15). Assuming the plaintiff’s cost to be Rs 10,000 (represented as 10) and the defendant’s cost to be Rs 1,00,000 (represented as 100) we get the equations:

(eq1) 15p — 10 = z (American rule)

(eq2) 15p — (1 — p) * 110 = z (English rule)

And assuming if defendant’s cost is the same as before (i.e. 10,000) then we get the other two equations:

(eq1) 15p — 10 = z (American rule)

(eq2) 15p — (1 — p) * 20 = z (English rule)

Plotting the two graphs, we get:

Graph 3 Graph 4

Graph 3 represents when the defendant’s cost is Rs 1,00,000 whereas Graph 4 represents when the defendant’s cost is Rs 10,000. Observe that when the probability of the plaintiff winning suit is 0 then in Graph 3 his net loss will be 10 under American rule and 110 under English rule. On the other hand, observe under Graph 4, when the probability of the plaintiff winning suit is 0 then his net loss will be 10 under the American rule and 20 under the English rule.

Thus, an increase of the defendant’s fee from Rs 10,000 to 1,00,000 will lead to the plaintiff bearing an additional amount of Rs 90,000 in case he loses under the English rule but will be the same under American rule. Further, in case the probability of winning for the plaintiff is one (i.e. p=1), then he recovers only Rs 15,000 in both rules irrespective of the defendant’s cost. Thus, if plaintiff loses then he has to incur huge costs but in case he wins he is awarded only nominal costs.

The above analysis suggests why American rule is based on the public policy principle which requires that the honest plaintiff should not be frightened from asking for the aid of the law by fear of an extremely heavy bill of costs against him should he lose. It is to be further kept in mind that when the defendant incurs more expenditure in hiring a more experienced lawyer then the probability of the plaintiff winning can also reduce irrespective of whether the claim brought by the plaintiff was justified or not and by application of English rule, in case he loses he will have to bear extra expenditure for no fault of his.

The same principles can be applied in the case where the plaintiff incurs a much higher cost as compared to the defendant and can prejudice the defendant when the English rule is applied strictly.

It is also important to see these rules in the context of India where plaintiffs (many times) with fewer resources are forced to litigate against corporations and Government, especially in cases of illegal takeover of property. The cumbersome process already acts as a deterrent for people to approach the judiciary, and the added burden of extremely high cost in case one loses will force people to not file any case against the Government and big corporations. The costs are to be transferred keeping in view that the justice is to be provided to parties and how applying a particular cost formula can have ramifications on the future litigations. Corporations and Government can easily compensate plaintiffs given the mammoth resources available to them however same would not be possible for the plaintiffs in every case.

Case 2: Legal aid

Another case to be kept in mind is the case of legal aid. Public legal aid directly funds the parties through State money — usually by waiving court fees, often (though not necessarily) by paying for lawyers, and possibly even by covering the expenses of evidence taking. It thus distributes litigation costs extremely widely: these costs are ultimately borne by the taxpayers in the respective State entity (federation, State, province, etc.).25

The Indian Constitution26 mandates that the State “secure that the operation of the legal system promotes justice on a basis of equal opportunity, and shall, in particular, provide free legal aid, by suitable legislation or schemes or in any other way, to ensure that opportunities for securing justice are not denied to any citizen by reason of economic or other disability”. Accordingly, India has enacted the Legal Services Authorities Act, 198727 (brought into force 1995) and constituted the National Legal Services Authority as well as the State Legal Services Authorities.

However, the application of cost-shifting rules is not suggested in the case of legal aid. To take the previous example where the expected award is Rs 15,000 (represented as 15) and defendant’s legal cost is Rs 10,000 (represented as 10) and the plaintiff’s legal cost will be 0 due to the effect of legal aid (i.e. 10,000 being spent by the legal aid authority), we get the following equations:

(eq1) 15p = z (American rule)

(eq2) 15p — (1 — p) * 10 = z (English rule)

It will be observed that if the plaintiff’s probability of winning the suit is 1 then the plaintiff’s net gain is Rs 15,000 in both cases. However, from this Rs 15,000, Rs 10,000 has been incurred by the legal aid authority hence plaintiff should be only entitled to Rs 5000. Further, where one party is legally aided and the other is privately funded, the latter, when successful, should not normally receive his or her costs against the legal aid fund.28

Thus, as observed from the above analysis, while the English rule ensures meritorious claims and deters frivolous claims, its application may not be desirable in every case especially when there is a huge difference between the paying capacity of the parties to the suit since the same can lead to one party being charged overly for its claim often leading to a situation where costs will exceed the value of the claim.

It is thus suggested, that the courts in India should not strictly enforce either of the rules. Courts should look into various factors including the background of litigants before awarding the cost. India being a developing country, it would not be in its best interest to provide the strict application to either English or American rule.

Conclusion

This piece thus analysed the English and American rules of cost-shifting and reaches the conclusion that neither of the rules can be applied absolutely. Different circumstances will require the application of different rules and many times a mix of both rules. In India, when most people cannot afford litigation fees, it will be imprudent on the part of courts to recklessly apply the English rule just because CPC demands so. It is suggested that the court delves deeper into each case and decides the application of the rule on a case-to-case basis.

*National Law School of India University. Author can be reached at: ashwin.goel@nls.ac.in.

1. Mathias Reimann (ed.), Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure: A Comparative Study (Springer, 2012) p. 9.

2. Mathias Reimann (ed.), Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure: A Comparative Study (Springer, 2012) p. 9.

3. Richmond v. Pheaa, 6 Pa. Commw. 612 : 297 A 2d 544 (1972); Statute of Gloucester 1275, 6 Edw. 1, c. 1.

4. Geoffrey Woodroffe, “Loser Pays and Conditional Fees ¾ An English Solution?”, (1997) 37 Washburn Law Journal 345, 346.

5. Mathias Reimann (ed.), Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure: A Comparative Study (Springer, 2012) p. 20.

6. Mathias Reimann (ed.), Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure: A Comparative Study (Springer, 2012) p. 20.

7. 3 Dall 306 : 1 L Ed 613 : 3 US 306 (1796).

8. Wynn v. Brooke, 5 Rawle 106, 106-08 (Pa. 1835).

9. St. Peter’s Church v. Beach, 26 Conn. 355, 365 (Conn. 1857).

10. Oelrichs v. Spain, 15 Wall 211 : 21 L Ed 43 : 82 US 211 (1872).

11. Ackerman v. Kaufman, 15 P 2d 966 (Ariz. 1932) : 41 Ariz. 110, 114 (1932).

12. Fleischmann Distilling Corpn. v. Maier Brewing Co., 1967 SCC OnLine US SC 96 : 18 L Ed 2d 475 : 386 US 714, 718 (1967).

13. Code of Civil Procedure, 1908.

14. Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, S. 35.

15. Mathias Reimann (ed.), Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure: A Comparative Study (Springer, 2012) p. 173.

16. Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, S. 35(2).

17. Mathias Reimann (ed.), Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure: A Comparative Study (Springer, 2012) p.173.

18. Salem Advocate Bar Assn. (2) v. Union of India, (2005) 6 SCC 344, quoted in Mulla, The Code of Civil Procedure, (17th Edn., 2007) p. 614 (emphasis added).

19. Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, S. 122.

20. Delhi High Court Rules, 2024.

21. Delhi High Court Rules, 2024, Ch. 11 Judgment and Decree, Part C Award of Costs in Civil Suits, R. 1.

22. Jaime Leigh Loos, “The Effect of a Loser-Pays Rule on the Decisions of an American Litigant”, (2005) 7 Major Themes in Economics 33.

23. Jaime Leigh Loos, “The Effect of a Loser-Pays Rule on the Decisions of an American Litigant”, (2005) 7 Major Themes in Economics 33.

24. Jaime Leigh Loos, “The Effect of a Loser-Pays Rule on the Decisions of an American Litigant”, (2005) 7 Major Themes in Economics 36.

25. Mathias Reimann (ed), Cost and Fee Allocation in Civil Procedure: A Comparative Study (Springer, 2012) p. 36.

26. Constitution of India, Art. 39-A.

27. Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987.

28. Geoffrey Woodroffe, “Loser Pays and Conditional Fees ¾ An English Solution?”, (1997) 37 Washburn Law Journal 347.