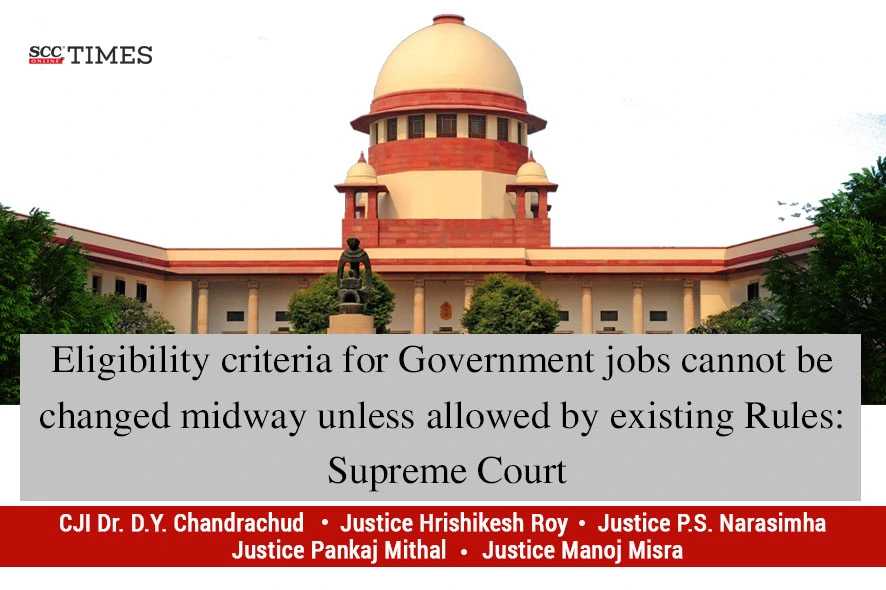

Supreme Court: In a matter posing a legal question of whether the criteria for appointment to a public post could be altered by the authorities concerned in the middle or after the process of selection has started, the 5-Judge Constitution Bench comprising of Dr. DY Chandrachud , CJI., Hrishikesh Roy, PS Narasimha, Pankaj Mithal and Manoj Misra*, JJ. held the following:

-

Recruitment process commences from the issuance of the advertisement calling for the applications and ends with filling up of vacancies;

-

Eligibility criteria for inclusion in the select list cannot be altered midway, unless explicitly allowed by the prevailing rules or the original advertisement, provided it does not contradict those rules;

-

If such change is permissible under the extant rules or advertisement, the change has to meet the standard of Articles 14 of the Constitution and must satisfy the test of non —arbitrariness;

-

K. Manjusree v. State of A.P. (2008) 3 SCC 512. (deals with right to be placed in the select list), is good law and not in conflict with State of Haryana v. Subash Chander Marwaha, (1974) 3 SCC 220 (deals with the right to be appointed from the select list) into consideration. These cases dealt with altogether different issues.

-

Recruiting bodies subject to the extant rules may devise an appropriate procedure for bringing the recruitment process to its logical end, provided the procedure is transparent non-discriminatory, non-arbitrary, and has a rational nexus with the object sought to be achieved.

-

Extant Rules having statutory force are binding on the recruiting body both in terms of procedure and eligibility, however, where the rules are silent, the administrative instructions can fill in the gaps.

-

Placement in the select list does not give a candidate an indefeasible right to employment; the State or its instrumentality for bona fide reasons can chose to not fill up the vacancies, however, if vacancies exist the State or its instrumentality cannot arbitrarily deny appointment to a person within the zone of consideration.

Background:

The present case is concerned with the recruitment process for filling thirteen translator posts in the Rajasthan High Court, which required candidates to first appear for a written exam, followed by a personal interview. Twenty-one candidates participated in the process, but only three were declared successful by the High Court (administrative side). It was later revealed that the Chief Justice of the High Court had imposed a 75 per cent marks criterion for selection, which had not been mentioned in the original recruitment notification. This new criterion was applied retroactively, resulting in the selection of only three candidates and the exclusion of the remaining ones.

In response, three unsuccessful candidates filed a writ petition challenging the decision, arguing that the imposition of the 75 per cent cutoff amounted to “changing the rules of the game after the game is played,” which was impermissible. The High Court dismissed their petition in March 2010, prompting the appellants to approach the Supreme Court for relief.

In 2023, the three-judge bench acknowledged that applying the K. Manjusree (supra) ruling strictly to the present case would compel the Rajasthan High Court to recruit all thirteen candidates, rather than just three. However, the Bench expressed that such a rigid application, without further scrutiny, might not serve the larger public interest or the goal of creating an efficient administrative framework. To support this view, the Bench referenced the Subash Chander Marwaha case, which dealt with the recruitment of civil judges in Haryana, noting that this ruling had not been considered in the Manjusree case. As a result, the matter was referred to a larger Bench for a conclusive ruling.

Issues, Analysis and Decision:

The Court explained that public services broadly fall in two categories. One, where services are in connection with the affairs of the State/ Union. Second, where services are under the instrumentalities of the State. In either category, law governing recruitment must conform to the overarching principles enshrined in Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution.

The Court noted that in various judicial pronouncements, the law governing recruitment to public services has been colloquially termed as ‘the rules of the game’. The ‘game’ is the process of selection and appointment. Courts have consistently frowned upon tinkering with the rules of the game once the recruitment process commences. This has crystallised into an oft-quoted legal phrase that “the rules of the game must not be changed mid-way, or after the game has been played”. Broadly speaking these rules fall into two categories. One prescribes the eligibility criteria (i.e., essential qualifications) of the candidates seeking employment; and the other stipulates the method and manner of making the selection from amongst the eligible candidates.

The Court reiterated that after commencement of the recruitment process the eligibility criteria is not to be altered because candidates even if eligible under the altered criteria might not apply by the last date under the belief that they are not eligible as per the advertised criteria. Such alteration/ change, therefore, deprives a person of the guarantee of equal opportunity in matters of public employment provided by Article 16 of the Constitution.

(a) When the recruitment process commences and comes to an end;

The Court reiterated that the process of recruitment begins with the issuance of advertisement and ends with the filling up of notified vacancies. It consists of various steps like inviting applications, scrutiny of applications, rejection of defective applications or elimination of ineligible candidates, conducting examinations, calling for interview or viva voce and preparation of list of successful candidates for appointment

(b) Basis of the doctrine that ‘rules of the game’ must not be changed during the game, or after the game is played;

The doctrine proscribing change of rules midway through the game, or after the game is played, is predicated on the rule against arbitrariness enshrined in Article 14 of the Constitution. Article 16 is only an instance of the application of the concept of equality enshrined in Article 14. Thus, Article 14 is the genus while Article 16 is a species. Article 16 gives effect to the concept of equality in all matters relating to public employment. These two articles strike at arbitrariness in State action and ensure fairness and equality of treatment.

The Court mentioned that the candidates participating in a recruitment process have legitimate expectation that the process of selection will be fair and non-arbitrary. The basis of doctrine of legitimate expectation in public law is founded on the principles of fairness and non-arbitrariness in government dealings with individuals.

(c) Whether the decision in K. Manjusree (supra) is at variance with earlier precedents on the subject;

The Court noted that the discernible ratio in K. Manjusree (supra) is that the criterion for selection is not to be changed after completion of the selection process, though in absence of rules to the contrary the Selection Committee may fix minimum marks either for written examination or for interview for the purposes of selection. But if such minimum marks are fixed, it must be done before commencement of the selection process.

The Court further noted that in the reference order the correctness of the decision in K. Manjusree has been doubted on two counts:

(a) if the principle laid down in K. Manjushree is applied strictly, the High Court would be bound to recruit 13 of the “best” candidates out of the 21 who applied irrespective of their performance in the examination held, which would not be in the larger public interest or the goal of establishing an efficient administrative machinery; and

(b) the decision of this Court in Subash Chander Marwaha (supra) was neither noticed in K. Manjusree nor in the decisions relied upon in K. Manjusree.

The Court viewed that the apprehension expressed in the referring order that all selected candidates regardless of their suitability to the establishment would have to be appointed, if the principle laid down in K. Manjusree is strictly applied, is unfounded, because K. Manjusree does not propound that mere placement in the list of selected candidates would confer an indefeasible right on the empanelled candidate to be appointed.

Afte taking note of Subash Chander Marwaha (supra), the Court observed that there was no change in the rules of the game qua eligibility for placement in the select list. There the select list was prepared in accordance with the extant rules. But, since the extant rules did not create any obligation on the part of the State Government to make appointments against all notified vacancies, this Court opined that the State could take a policy decision not to appoint candidates securing less than 55% marks. On the other hand, in K. Manjusree (supra), the eligibility criteria for placement in the select list was changed after interviews were held which had a material bearing on the select list. Thus, Subash Chander Marwaha (supra) dealt with the right to be appointed from the select list whereas K. Manjusree (supra) dealt with the right to be placed in the select list. The two cases therefore dealt with altogether different issues. Thus, K. Manjusree (supra) could not have been doubted for having failed to consider Subash Chander Marwaha (supra).

The Court remarked that “ the object of any process of selection for entry into a public service is to ensure that a person most suitable for the post is selected. What is suitable for one post may not be for the other. Thus, a degree of discretion is necessary to be left to the employer to devise its method/ procedure to select a candidate most suitable for the post albeit subject to the overarching principles enshrined in Articles 14 and 16 of the Constitution as also the Rules/ Statute governing service and reservation”.

Therefore, the Court viewed that the appointing authority/ recruiting authority/ competent authority, in absence of Rules to the contrary, can devise a procedure for selection of a candidate suitable to the post and while doing so it may also set benchmarks for different stages of the recruitment process including written examination and interview. However, if any such benchmark is set, the same should be stipulated before the commencement of the recruitment process. But if the extant Rules or the advertisement inviting applications empower the competent authority to set benchmarks at different stages of the recruitment process, then such benchmarks may be set any time before that stage is reached so that neither the candidate nor the evaluator/ examiner/ interviewer is taken by surprise.

(d) Whether the above doctrine applies with equal strictness qua method or procedure for selection as it does qua eligibility criteria;

The Court said that the recruiting bodies can devise an appropriate procedure for successfully concluding the recruitment process provided the procedure adopted has been transparent, non-discriminatory/ non-arbitrary and having a rational nexus to the object sought to be achieved.

(e) Whether procedure for selection stipulated by Act or Rules framed either under the proviso to Article 309 of the Constitution or a Statute could be given a go-bye;

The Court said that where there are no Rules or the Rules are silent on the subject, administrative instructions may be issued to supplement and fill in the gaps in the Rules. In that event administrative instructions would govern the field provided they are not ultra vires the provisions of the Rules or the Statute or the Constitution. But where the Rules expressly or impliedly cover the field, the recruiting body would have to abide by the Rules.

(f) Whether appointment could be denied by change in the eligibility criteria after the game is played.

After relying on Shankarsan Dash v. Union of India, (1991) 3 SCC 47, the Court said that a candidate placed in the select list gets no indefeasible right to be appointed even if vacancies are available. However, the State or its instrumentality cannot arbitrarily deny appointment to a selected candidate. Therefore, when a challenge is laid to State’s action in respect of denying appointment to a selected candidate, the burden is on the State to justify its decision for not making appointment from the Select List.

Also read: Changing the Rules of the Game: Selection and Appointment in Public Service

[Tej Prakash Pathak v. Rajasthan High Court, 2024 SCC OnLine SC 3184, decided 07-11-2024]

*Judgment Authored by: Justice Manoj Misra