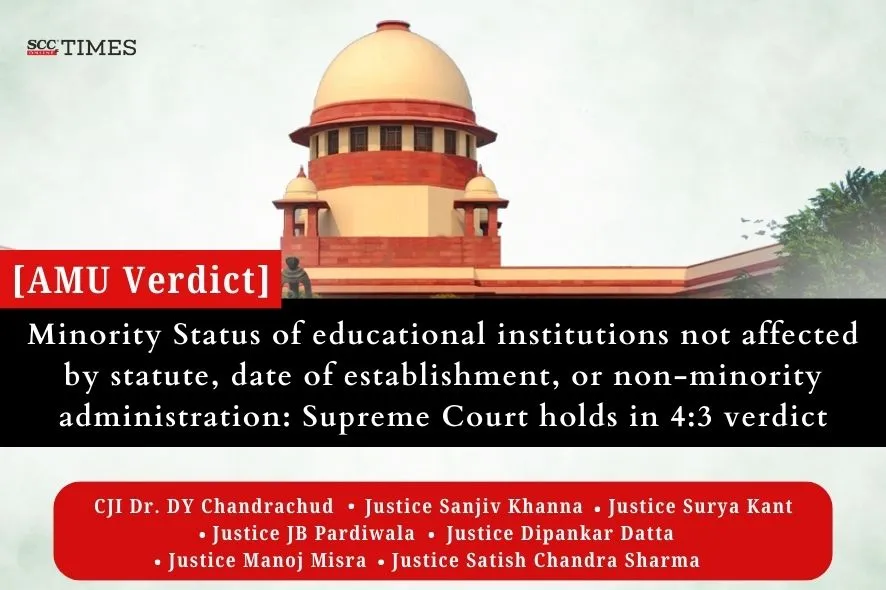

Supreme Court: In an appeal against Allahabad High Court’s Order in Naresh Agarwal (Dr.) v. Union of India, 2005 SCC OnLine All 1705, whereby, Aligarh Muslim University’s (‘AMU’) action of 50 percent seat reservation in postgraduate medical courses for Muslim candidates by claiming it to be a minority institution, was struck down and held that AMU cannot have an exclusive reservation because it is not a minority institution, the Seven-Judge Constitution Bench comprising of Dr. DY Chandrachud, CJ., Sanjiv Khanna, Surya Kant, JB Pardiwala, Dipankar Datta, Manoj Misra and Satish Chandra Sharma, JJ. in 4: 3 overruled the Five-Judge Bench verdict in S. Azeez Basha v. Union of India, 1967 SCC OnLine SC 321, which held that an institution incorporated by a statute cannot claim to be a minority institution, hence AMU as created by an Act of Parliament, is not a minority institution so as to be covered under Article 30 of the Constitution of India.

The Chief Justice authored the majority opinion in the case, joined by Justices Sanjiv Khanna, JB Pardiwala, and Manoj Misra. In contrast, Justices Surya Kant, Dipankar Datta, and Satish Chandra Sharma each wrote separate dissenting opinions, outlining their differing perspectives on the matter.

Issues:

- Whether an educational institution must be both established and administered by a linguistic or religious minority to secure the guarantee under Article 30?

- What are the criteria to be satisfied for the ‘establishment’ of a minority institution? Whether Article 30(1) envisages an institution which is established by a minority with participation from members of other communities;

- Whether a minority educational institution which is registered as a society under the Societies Registration Act 1860 soon after its establishment loses its status as a minority educational institution by virtue of such registration; and

-

Whether the decision of this Court in Prof. Yashpal v. State of Chhattisgarh (2005) 5 SCC 420 and the amendment of National Commission for Minority Educational Institutions Act 2005 in 2010 have a bearing on the question formulated above and if so, in what manner.

Analysis and Decision:

Scope of Article 30 of the Constitution

The Court said that the purpose of Article 30(1) is to ensure that the State does not discriminate against religious and linguistic minorities which seek to establish and administer educational institutions, and also to guarantee a ‘special right’ to religious and linguistic minorities that have established educational institutions.

The Court highlighted that “this special right is the guarantee of limited State regulation in the administration of the institution. The State must grant the minority institution sufficient autonomy to enable it to protect the essentials of its minority character. The regulation of the State must be relevant to the purpose of granting recognition or aid. This special or additional protection is guaranteed to ensure the protection of the cultural fabric of religious and linguistic minorities”.

Indicia for a Minority Educational Institution

The Court referred to Article 19(1)(a) to understand what it means to conjunctively read two words in a provision. It noted that Article 19 guarantees the fundamental right to free speech and expression. The guarantee of freedom of expression is, however, not dependent on freedom of speech. They are two separate rights.

The Court stated the situation differs with regard to the rights to establish and administer outlined in Article 30. It reiterated that the rights to establish and administer must be read conjunctively and not disjunctively.

The Court reiterated that Article 30 does not prescribe conditions which must be fulfilled for an educational institution to be considered a minority educational institution. Article 30 confers two group rights on all linguistic and religious minorities: the right to establish an educational institution and the right to administer an educational institution.

Also Read:

The Court emphasised that the right to establish an educational institution guaranteed to the minority is not a special right, as it is a right which is available to every citizen under Article 19(1)(g) and to minority and non-minority religious denominations under Article 26. The special right that the provision guarantees to religious and linguistic minorities relates to the administration of educational institutions “of their choice”.

The Bench mentioned that Article 30(1) cannot extend to a situation where the minority community establishes an educational institution that has no intention of administering it. A religious or linguistic community may establish an educational institution and yet not administer it, as evident from Article 28(2) of the Constitution which states that Article 28(1) will not apply to an educational institution which is administered by the State but was established under an endowment or a trust which requires religious instruction to be imparted. Thus, putting a ‘minority’ tag on such an educational institution merely because it has been established by a person or a group belonging to a religious or linguistic minority would not be permissible under Article 30(1).

Therefore, the Bench underscored that to determine whether an educational institution is a minority educational institution, a formalistic test such as to whether it was established by a person or group belonging to a religious or linguistic minority is not sufficient. The tests adopted must elucidate the purpose and intent of establishing an educational institution for the minority. Both the establishment and the administration by the minority must be fulfilled cumulatively for that.

Applicability of Article 30 to a ‘University’ established before the commencement of the Constitution

The Court said that a distinction between educational institutions established before and after the commencement of the Constitution cannot be made for the purposes of Article 30(1). Article 30 will stand diluted and weakened if it is to only apply prospectively to institutions established after the commencement of the Constitution. The protection and guarantee, if made applicable to only institutions established after the commencement of the Constitution, would debase and defile the object and purpose of the provision.

“The adoption of the Constitution reflects a break from the system of sovereign and potentate government under the colonial regime and the dawn of governance based on the rule of law. It secures to the minority educational institutions, rights under the Constitution from the date of its commencement”

The Court highlighted that with the commencement of the Constitution, citizens were granted the protective cover of Part III which enshrines the fundamental rights. In line with Article 372 read with Article 13(1), the Court stated that any law predating the Constitution that contradicts fundamental rights would be deemed unconstitutional. However, the Court clarified that this does not mean that such pre-Constitution laws cannot benefit from the additional protection provided by fundamental rights. The right to administration in Article 30(1) is one such protection. Thus, educational institutions established by religious and linguistic minorities before the commencement of the Constitution will also receive the special protection guaranteed by Article 30(1): the right to administration without the infringement of their minority character.

The Bench concluded that the teaching universities and colleges serve the common function of educating students. No distinction between the two can be drawn for the purposes of Article 30(1) which guarantees minorities the right of greater autonomy in the administration of educational institutions to curate a model of education which best serves the interests of the community.

While rejecting the submission that a person did not have the power to ‘establish’ a university before the enactment of the UGC Act, the Court explained that the words ‘establishment’ and ‘incorporation’ cannot be interchangeably used. They connote different meanings. The former refers to founding an institution, which in the case of teaching colleges that were converted to universities would refer to any person or community who undertook the efforts to establish the teaching college.

Concerning the issue of the status of minority character of the institution upon the incorporation of the University, the Court said that the minority character of institutions cannot be rejected if they were conferred a legal character by a statute enacted prior to 1950, as the enactment was necessary to award degrees recognized by the British government, allowing graduates to gain degree recognition and secure employment. The enactment of the statute is a ministerial and a legislative act, which confers juristic personality as well as legal rights in terms of the law in force. The statute grants the power to the educational institution to confer the degrees.

The Bench while remarking that incorporation by way of statute is a legal requirement, rejected the argument that compliance with legal requirement would be tantamount to the ‘establishment’ of an institution by the Legislature, and thereby the linguistic and religious minority forgo the guarantees and protection under clause (1) of Article 30 of the Constitution.

The Court concluded that compliance with the legal requirement to secure a benefit provided by the State cannot be on terms that require the relinquishment of fundamental rights. An interpretation that leans towards this consequence must not be adopted. Thus, the minority character of an educational institution could not have been denied merely because it was converted to a university through a legislative enactment.

The Court concluded that the reference in Anjuman-e-Rahmaniya v. District Inspector of Schools1 of the correctness of the decision in Azeez Basha (supra) was valid. The reference was within the parameters laid down in Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra Community v. State of Maharashtra, (2005) 2 SCC 673.

The Court further laid down the factors which must be used to determine if a minority ‘established’ an educational institution:

- The indicia of ideation, purpose and implementation must be satisfied. First, the idea for establishing an educational institution must have stemmed from a person or group belonging to the minority community; second, the educational institution must be established predominantly for the benefit of the minority community; and third, steps for the implementation of the idea must have been taken by the member(s) of the minority community; and

-

The administrative set up of the educational institution must elucidate and affirm (I) the minority character of the educational institution; and (II) that it was established to protect and promote the interests of the minority community.

The Court overruled the view taken in Azeez Basha (supra) that an educational institution is not established by a minority if it derives its legal character through a statute.

Further, the Court said that the question of whether AMU is a minority educational institution must be decided based on the principles laid down in this judgment. Thus, it placed before the regular bench for deciding whether AMU is a minority educational institution and for the adjudication of the appeal from the decision of the Allahabad High Court in Aligarh Muslim University v. Malay Shukla, 2006 SCC OnLine All 22072 after receiving instructions from the Chief Justice of India on the administrative side.

[Aligarh Muslim University v. Naresh Agarwal, 2024 SCC OnLine SC 3213, decided on 08-11-2024]

Buy Constitution of India HERE

1. W.P.(C) No. 54-57 of 1981

2. Judgment in Special Appeal No 1321 of 2005 and connected matters, Allahabad High Court