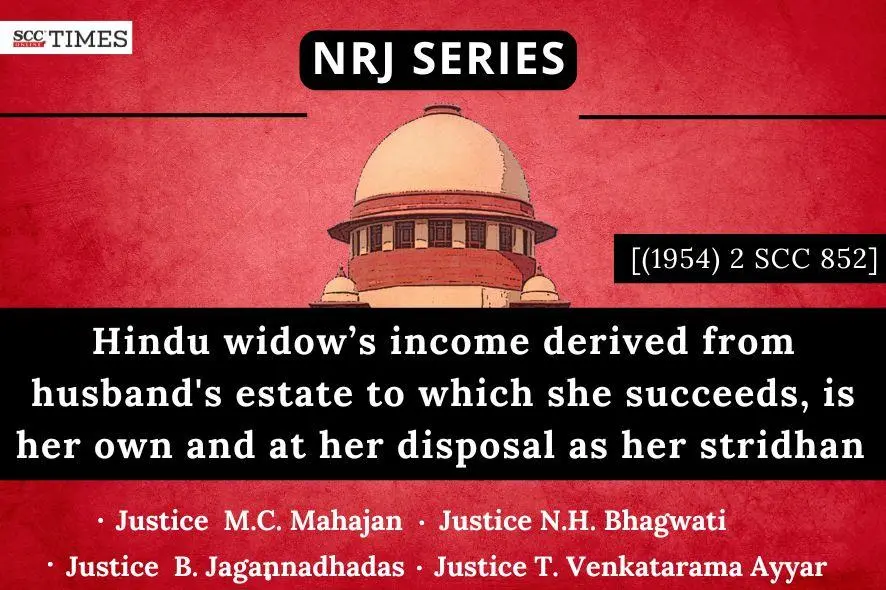

Supreme Court: The present appeal was filed against the judgment of the Calcutta High Court (‘the High Court’), which arose out of a suit for recovery of a premises, Badruddin Street, Calcutta (‘the suit premises’), from respondents who were the trustees under a deed of settlement executed by Rampeary, widow of Sagarmull, on 09-05-1935, by which the said property was settled by her in trust for the benefit of certain idols installed in a temple erected by her. The 4-Judges Bench of M.C. Mahajan, N.H. Bhagwati, B. Jagannadhadas*, and T. Venkatarama Ayyar, JJ., held that money invested in purchase of the suit property was the absolute property of Rampeary and reversioners had no title to the same and there was no restriction on widow’s enjoyment of money which had come in her hands as cash. The Supreme Court opined that the income which a Hindu widow derived from the estate of her husband to which she succeeded was entirely her own and at her disposal as her stridhan.

Background

Sagarmull died childless in 1907 leaving his widow as his sole heir. Sagarmull had four annas share in a business which was carried in a co-partnership with the three brothers of his adoptive father, Ramlal and the business continued till 1918, when Rampeary filed a suit against other partners for dissolution of partnership, for a declaration that she was entitled to four annas share in the partnership and for accounts. The said suit was compromised, and a consent decree was passed on 25-11-1920, and Rampeary was entitled to three annas share and that the accounts of the business would be taken from Sambat years 1963 to 1977 and that Rampeary would be entitled to the amount so found due on taking accounts with certain deductions.

There was a further settlement between the parties as per which Rampeary was declared entitled to Rs 1,43,332-9-0 on taking accounts and that Rs 16,000 thereof had been recovered by her and that Rs 1,27,332-9-0 remained due and that the said amount was to be paid with interest at nine annas per cent, per mensem and the amount should be dealt with in accordance with the terms of the consent decree made on 25-11-1920. But no money was paid in pursuance of this settlement and Rampeary was obliged to take out proceedings in execution in January 1922 and Rs l,27,333-9-0 was deposited with the Sheriff to the credit of the suit. Thus, there was further settlement between parties regarding interest and costs, etc., by which she got certain other payments in adjustment of the balance of her claim and was permitted to draw the entire amount with the Sheriff. Thus, Rampeary received Rs 16,000 from the judgment debtors on 17-08-1922 and obtained payment from the Sheriff on 12-09-1922, of Rs 1,23,828-7-9 after deductions of poundage and other expenses.

On 26-09-1922, she purchased the suit premises for Rs 1,45,000 and both the courts below found that the entire amount except Rs 7500 came from the moneys which Rampeary received from the various compromises in the suit relating to the dissolution of partnership and the execution proceedings which followed thereupon. Rampeary died in October 1944 but before her death, she executed the deed of trust dated 09-05-1935, dedicating all her movable and immovable properties to the idols in a temple and created a religious trust. Appellants-plaintiffs stated that the money which was invested in the purchase of the suit property was Sagarmull’s estate and that appellants as between them were entitled to the same as the reversioners to Sagarmull’s estate and that the deed of trust created by Rampeary was not binding on them. Respondents, on the other hand, submitted that the money which was invested in the purchase of the suit property was Rampeary’s absolute property and that she was competent to execute the deed of trust and that appellants had no title to the same.

The Trial Court upheld appellants’ contention and decreed the suit subject to the payment of Rs 7500 by appellants and on appeal, the High Court agreed with respondents’ contentions and thus, reversed the Trial Court’s decree and dismissed the suit. Thus, the present appeal was filed.

Analysis, Law, and Decision

The Supreme Court stated that as the business of the partnership was carried on for over 12 years after Sagarmull’s death and up to the date when the consent decree of November 1920, was passed, the sum that was found due on taking accounts as per terms of the consent decree would represent, not only the husband’s share of the assets of the partnership with the accumulated income, if any belonging to her husband by the date of his death in 1907 but also all the subsequent accumulated profits after 1907 up to the date of taking of accounts.

The Supreme Court thus stated that the amount received by Rampeary was the result of further compromises in two stages, but the Supreme Court noted that it was specifically stated in the second consent decree dated 19-07-1921, that the amount settled was the sum found due on taking accounts which must have been in pursuance of the terms of the first consent decree of 26-11-1920. Thus, the Supreme Court opined that there could be no reasonable doubt that the moneys realized by Rampeary in execution and forming the major portion of the consideration for the purchase of the suit property must be taken to represent not merely the assets and the income representing her husband’s share in the business by the date of his death but also the further accumulated profits subsequent thereto for a period of about 13 years and arising out of the husband’s share which devolved upon her as the heir of her husband.

The Supreme Court opined that the income which a Hindu widow derived from the estate of her husband to which she succeeded was entirely her own and at her disposal as her stridhan. Thus, all accumulations of such income in her hands were her stridhan.

The Supreme Court stated that the issue for consideration was “whether by the terms of the compromise decree, it was specifically intended that the entire amount to be realized under it was to be treated as being the estate of Rampeary’s husband?”.

The Supreme Court noted that the compromise of 19-7-1921, which fixed the actual amount on taking accounts, specifically provided that the amount would be dealt with according to the terms of the consent decree dated 25-11-1920. Thus, the compromises might be taken to have provided that the sum found due to Rampeary would be invested by appellant-judgment debtors, within six months, in the purchase of some immovable properties to be selected by Rampeary and also that if property was so purchased, the income of the immovable property would be enjoyed by her for her life and after her death it would go to her son to be adopted, but no adoption was made. The Supreme Court opined that if this clause had imposed an obligation on Rampeary to purchase immovable properties out of the moneys to be paid into her hands and if the present property had been purchased in pursuance of that obligation the case for appellants might have stood on a different footing, but that clause imposed no such obligation on Rampeary.

The Supreme Court stated that what was contemplated was purchase of certain immovable property of Rampeary’s choice out of the money due to her, by the judgment-debtors, within six months of the ascertainment of the money and the payment of the balance to her. But it was also specifically provided that if the money was not so invested, the whole of the amount was to be paid to her. The correspondence between the parties subsequent to the date of the second consent decree dated 19-07-1921, showed that appellants-judgment debtors were called upon by Rampeary to purchase certain houses and to pay over the balance. But for some reason, the judgment debtors did not make any purchase in terms of the compromise within the specified period of six months and Rampeary was obliged to take steps in execution in 1922 to realize the moneys due to her.

The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court that a very substantial portion of the money, when it came into the hands of Rampeary, was her own money, with no restrictions on her enjoyment thereof and unlike in the case of immovable property, in which a portion of the money was contemplated to be invested before actual payment was made to her, there was no term in the compromise decree restricting her enjoyment of the money which came into her hands as cash. The Supreme Court stated that there was no term which required her to invest the said money and enjoy only the interest thereon. The Supreme Court further stated that Rampeary was intended to be the absolute owner of the money which came into her hands was confirmed by a Clause in the compromise decree of 1920 which stated that “The plaintiff will be entitled to adopt a son unto her husband who will be entitled to all the properties that the plaintiff may get or leave at the time of her death”.

The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court’s view that appellants did not make out their case and thus the appeal was dismissed with costs.

[Mani Bai v. Babu Pritam Chand, (1954) 2 SCC 852, decided 06-12-1954]

*Judgment authored by: Justice B. Jagannadhadas

Advocates who appeared in this case :

For the Appellants: M.C. Setalvad, Attorney General for India (B.P. Maheshwari, Advocate, with him), for the Appellants;

For the Respondents: Atul Chandra Gupta, Senior Advocate (Naunit Lal, Advocate, with him), for Respondents 4, 11, 12, and 14

** Note: Stridhan

Stridhan is the property, both movable and immovable, and gifts, etc., received by a woman prior to her marriage, at the time of her marriage, during childbirth and during her widowhood. In the case of a widow, the property inherited from her husband is considered the woman’s estate, and she holds it as a limited owner. Nobody can possess or absorb stridhan of any woman and if the husband or the in-laws try to misappropriate the stridhan, then the woman is guaranteed full right to get her ownership back as she is the sole owner of her stridhan even if she gives someone to take in care of such property.