India has consistently emerged as an attractive destination for foreign investment in the world.1 This heralds a positive sign for India’s commitment to become a $30 trillion economy by 2047.2 With more foreign investors poised to enter the Indian markets, a win-win outcome, in case of any conflict, would entail the preservation of business relationships between the parties.3 Over recent years, arbitration has gone beyond the contours of an alternative for the swift resolution of commercial disputes,4 however, with time, it has become an expensive and lengthy alternative to litigation.5

While India is giving the necessary impetus to evolve itself as a global arbitration hub,6 mediation, on the other hand, has emerged as a similar alternative to litigation. With a pendency of approximately 74,526 arbitration cases in the country,7 the Parliament has enacted the Mediation Act, 2023 (Mediation Act) to ensure the ease of doing business in India.8 While the roots of this legislation lay in the Civil Procedure Code (Amendment) Act, 19999, and in Salem Advocate Bar Assn. (II) v. Union of India10, its branches have spread to facilitate, inter alia, institutional mediation for the resolution of commercial disputes.11 The popularity and preference for mediation have also surfaced through the Indian Government’s recent Notification with respect to contracts where the Government is a party except in low-value disputes (not exceeding Rs 10 crores).12 The reasons for non-preference to arbitration, as discussed earlier, inter alia, are increased time and expense, non-finality, and the common practice of challenging awards leading to only litigation at the end.13

Against this backdrop, this article proceeds with a twofold aim: first, the authors analyse statistics on domestic arbitration and mediation to conclude why mediation is needed. Second, based on statistics, we identify certain pitfalls and provide solutions to make mediation an effective and efficient dispute resolution mechanism in India.

India as a global arbitration hub: Likely or unlikely?

The Indian Government has come up with the draft Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024 which, inter alia, seeks to introduce an appellate mechanism against orders rejecting a Section 11 petition for the appointment of arbitrators.14 Furthermore, the Bill sets out strict timelines with regard to Section 8(1) (reference to arbitration by courts), Section 16 (decision on jurisdiction), etc.15 While these timelines may look in a positive direction, they also run the risk of extending delays in arbitration. In any event, the discussion below would substantiate how the timelines in the present statutory framework have been adhered to.

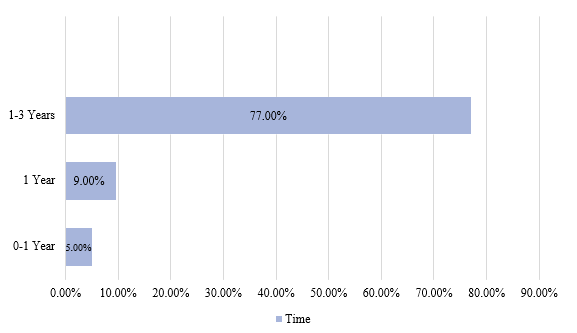

Recent arbitration surveys and reports offer reliable statistics regarding the State of arbitration in India. The Arbitration Survey Report (Report) reveals that there has been a significant decline in the level of satisfaction with arbitration as a method of dispute resolution.16 This dissatisfaction, inter alia, is largely due to the time taken in arbitrations which is mostly more than what has been mandated in the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.17 A similar view has been expressed in the PwC Report on the practices towards arbitration (PwC Report) in India.18 Herein, it must be noted that Section 29-A of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 inserted via the 2019 Amendment, has prescribed twelve months from the date of completion of pleadings as the timeline for completion of arbitration extendable by six months by mutual consent of the parties.19

Extracted from: PwC (Corporate Attitudes and Practices towards Arbitration in India)

According to the Survey of Dispute Resolution in India (Survey) it is obvious that the preference for arbitration is driven by three major factors: (i) flexibility of procedure; (ii) speed; and (iii) expertise of arbitrators.20 However, as the Reports and Survey both suggest, delays have plagued arbitration in the Indian landscape. The situation is exacerbated during challenges to arbitral awards. In Delhi, 70% of cases advance from an initial challenge under Section 34 to a subsequent appeal under Section 37, while in Bombay, this figure increases to 90%.21 On average, a Section 34 challenge adds 3.6 years to the process, and a Section 37 appeal extends it by an additional 5.8 years.22 Thus, the non-finality of awards has become another persisting issue in arbitration.

On the other hand, mediation while offering a flexible procedure and mediator training, is also leading to faster resolution of disputes with very “rare” instances of parties not adhering to the agreed settlement — unlike arbitration where the rate of compliance may be low.23 While the latest data for the average number of mediation sessions is scanty, the Bangalore Mediation Centre records an average of only 1.16 sessions per case with an average time of 144.31 minutes.24 In business relationships where there is a need to preserve them, prolonged proceedings would only enhance the possibility of a strained relationship which can be avoided through consensus and collaboration.25

Mediation in India: How far is it faring?

Section 89 of the Civil Procedure Code (CPC), 1908 contemplates mediation ordered by a court i.e. with the court’s involvement whereas Section 12-A of the Commercial Courts (CC) Act, 2015 contemplates mediation without any involvement of the Court as it is done prior to the institution of the suit.26 However, the Mediation Act has included pre-institution mediation within court annexed mediation.27 It is well-settled that mediation can provide a cost-effective and quick extrajudicial resolution of disputes in civil and commercial matters through processes tailored to the needs of the parties. It has been observed by the Supreme Court that agreements resulting from mediation are more likely to be complied with voluntarily and are more likely to preserve an amicable and sustainable relationship between the parties.28

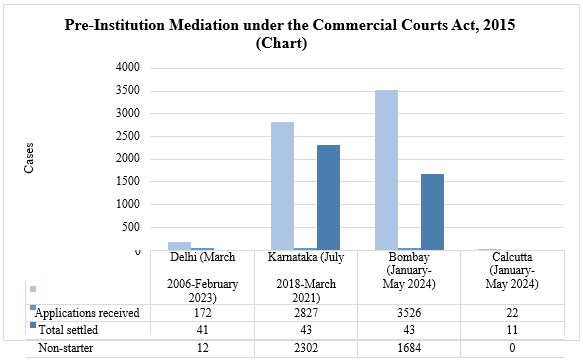

While the data on the implementation of commercial mediation in India is scanty, in Delhi, 172 applications were received to initiate pre-institution mediation. Out of these, 12 cases were non-starter cases.29 A non-starter case is one where either party refuses to participate in mediation, does not respond, or does not have sufficient authority to settle the case, etc. Data from Karnataka reveals that 2302 cases out of a total of 2827 applications received appeared to be non-starters.30 Bombay followed similar steps.31 The situation appears to be exacerbated on a perusal of data from Calcutta as the volume of applications received for pre-institution mediation is far lower let alone non-starters on the rise.32

Note: The 3526 applications received in Bombay include 1849 cases pending on 1-1-2024

Previously, the Supreme Court (SC) had settled the dust holding pre-institution mediation under Section 12-A mandatory.33 However, on a plain reading, statistics reveal that most pre-instituted mediations resulted in either party not appearing or participating in the process rendering the mandatory nature of Section 12-A of the CC Act practically ineffective. This outcome stems from the below-extracted paragraph which reflects how the Court failed to explain the scope of “exhausting” the remedy under Section 12-A. In para 62 of the judgment, the SC observed:

62. …Section 12-A declares that the plaintiff must exhaust the remedy of pre- litigation mediation. What, apparently is required is that the suit cannot be filed except after the remedy of pre-litigation mediation, contemplated under the Act and the Rules, is attempted and exhausted….34 (emphasis supplied)

It is patently clear that a non-starter case amounts to exhaustion of remedy for the plaintiff. However, on a careful perusal, the plaintiff’s remedy under Section 12-A rests upon the willingness of the defendant to appear or participate in mediation. Exhausting a remedy must not mean the institution of mediation but rather its conduction. In State Bank of Hyderabad v. S.P. Savithri, it was observed that:

11. …exhausting alternative remedy does not mean a mere filing of an appeal but inviting an order on merit after adjudication. In the absence of such adjudication on merits, it cannot be contended that the petitioner has exhausted the remedy of statutory appeal.35 (emphasis supplied)

It is, therefore, necessary that the mandatory nature of Section 12-A must be enforced in a way that does not impose an obligation upon the plaintiff for the institution, but also upon the defendant to participate in such pre-litigation mediation to give spirit to the object of the provision.

Making the cut: Fortifying the mediation process

It is preferred by investors, especially foreign investors, to avoid legal battles as it ensues intricate complexities of municipal law with it. However, the parties’ non-appearance defeats the objective of Section 12-A starkly. Furthermore, while the object and purpose of the Mediation Act envisage compulsory pre-litigation mediation in matters of civil or commercial disputes,36 Section 5 has neutralised this intent using the phrase “parties…may voluntarily” making pre-litigation mediation discretionary upon the parties.37 With the onset of the new mediation era, steps must be undertaken to make the process robust and more efficient.

The steps may include first, an audit of the grants received by different mediation centres, Committees, and the yet-to-be-established Mediation Council of India under the Mediation Act to ensure proper utilisation of funds and transparency amongst the stakeholders. Second, in addition to a regular assessment of the settlement rate of mediation, a systematic feedback process from both counsels and parties should be put in place to ensure the establishment of an effective procedure for the selection of mediators. The parties, being interested parties, would better provide insight into the mediator’s role in facilitating communication between them and guiding them towards a mutually acceptable agreement. Lastly, to strengthen the existing mediation centres, an overseeing body can be set up for each State comprising members both from the Bench and the Bar.38 This expert body can play a role in adopting a grading system of mediators based on case resolution efficiency and industry expertise and the registered mediators can be appointed for disputes falling under their expertise thereby, facilitating the efficient conduction of mediation sessions between the parties.

Conclusion

In some jurisdictions, such as England, the United States, Australia, and Hong Kong, mediation has already been successful with a well-developed mediation infrastructure.39 In the US, less than 5% of cases raised in courts result in a full trial taking place given the extensive use of mediation.40 The former Justice M.M. Kumar of Punjab & Haryana High Court had observed:

“Mediation is extremely relevant to the justice delivery in India since it not only brings an end to the litigation pending before the courts but it also has cascading effects of bringing an end to bad blood between the parties and making them useful members of the society.”41

Furthermore, the Law Commission of India in its 126th Report has underscored the need for a litigation policy to avoid litigation to ease the burden on courts in India.42 To give effect to the above end, mediation is a suitable and emerging alternative to arbitration in India. The former Chief Justice of India, N.V. Ramana, acknowledged that mediation is increasingly gaining prominence in international commercial space as a dispute resolution mechanism.43

Thus, making commercial mediation a norm would not only complement the working of commercial courts but also place India as a leading investment hub across the world. The note of caution, however, comes with the onset of institutional mediation given that institutional arbitration fell flat largely due to a lack of knowledge.44 It is thus imperative for India to take a cue and act circumspectly while always remembering that mediation and arbitration are not alternatives to each other but complementary methods of speedy resolution of disputes.

* Partner, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co.

The Author acknowledges the work of Intisar Aslam, Fourth year BA LLB (Hons.) student at the National University of Study and Research in Law, Ranchi.

1. Dipen Sabharwal K.C. and Aditya Singh, “India’s Legal Reform in Dispute Resolution Encourages Foreign Investment, White & Case LLP , available at: <https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/investing-india-legal-reform-dispute>; Srijata Deb and Devika Chawla, “India: Preferred Destination for Foreign Investments”, Invest India, available at: <https://www.investindia.gov.in/team-india-blogs/india-preferred-destination-foreign-investments>; Ash Tiwari and Priya Shah, “Which Sectors are Hotspots for India Inbound M&A and FDI?”, Baker Mckenzie, available at: <https://www.bakermckenzie.com/en/insight/publications/2024/07/sectors-hotspots-india>; Krishan Arora and Devika Dixit, “What Budget 2024 Can Do to Get Foreign Investors to Bet on India”, Grant Thornton , available at: <https://www.grantthornton.in/insights/media-articles/what-budget-2024-can-do-to-get-foreign-investors-to-bet-on-india/>; Rohit Bhat, Vasuda Sinha and Stuti Gadodia, “India: A New Era for International Arbitration?”, Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, available at: <India: a new era for international arbitration? | Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer>.

2. Ruchika Chitravanshi, “India Growing Rapidly, to be $30 Trn Economy by 2047: FM Sitharaman”, Business Standard , available at: <https://www.business-standard.com/economy/news/india-s-economy-to-be- worth-30-trillion-by-2047-fm-nirmala-sitharaman-124011000638_1.html>.

3. Justice Swatanter Kumar (Retd.), Preface in Mediation Training Manual of India, (Mediation and Conciliation Project Committee); SAMADHAN | National Conference on Mediation at the Dawn of Golden Age [14-15 April], SCC Times <https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2023/04/15/national-conference-on-mediation-at-the-dawn-of-golden-age/>.

4. Ashish Tripathi, “Arbitration no Longer Alternative, But Preferred Method of Seeking Commercial Justice: CJI DY Chandrachud”, Deccan Herald (<https://www.deccanherald.com/india/arbitration-no- longer-alternative-but-preferred-method-of-seeking-commercial-justice-cji-d-y-chandrachud-3057141>.

5. Aditya Sondhi, “Arbitration in India — Some Myth Dispelled”, (2007) 19(2) National Law School of India Review , Article 4, National Law School of India Review , available at: <“Arbitration in India – Some Myth Dispelled” by Aditya Sondhi (nls.ac.in)>

6. Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015, Ss. 29-A and 29-B (Award to be made within 12 months of completion of pleadings, Insertion of 5th and 7th Schedule vis-à-vis conflict of interest); Press Information Bureau, Government of India, Valedictory Speech by Prime Minister at National Initiative towards Strengthening Arbitration and Enforcement in India <https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=151887>; Ministry of Law and Justice, Report of the High-Level Committee to Review the Institutionalisation of Arbitration Mechanism in India (2017)

<MergedFile (legalaffairs.gov.in)>; Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2019, S. 42-A, (Confidentiality); Ircon International Ltd. v. Afcons Infrastructure Ltd., 2023 SCC OnLine Del 2350 (Limited judicial interference vis-à-vis challenge to award); Vidya Drolia v. Durga Trading Corpn., (2019) 20 SCC 406 (Arbitrability); Amazon.com NV Investment Holdings LLC v. Future Retail Ltd., (2022) 1 SCC 209 (Recognition of emergency award). Tomorrow Sales Agency (P) Ltd. v. SBS Holdings Inc., 2023 SCC OnLine Del 3191 (Third-party funding is essential to ensure access to justice); Ministry of Finance ‒ Union Budget 2024-2025, Expenditure Profile, Assistance given to Autonomous/Grantee Bodies, p. 246 (Arbitration Council of India and Mediation Council of India Rs 50 lacs each and Rs 4 crore to India International Arbitration Centre), Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024; Dipen Sabharwal K.C. and Aditya Singh, “India’s Legal Reform in Dispute Resolution Encourages Foreign Investment”, White & Case LLP, available at: <https://www.whitecase.com/insight-our-thinking/investing-india-legal-reform-dispute>.

7. National Judicial Data Grid <https://njdg.ecourts.gov.in/njdgnew/index.php>. The figure includes original cases (District Courts), suit, petition, application, appeal, revision (High Courts), and registered and unregistered petition (Supreme Court).

8. Justice R.S. Chauhan (retd.), “Why the Mediation Act 2023 is a Great Leap Forward”, Moneycontrol , available at:<https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/opinion/why-the-mediation-act-2023-is-a-great-leap-forward-11738231.html>.

9. Civil Procedure Code (Amendment) Act, 1999, S. 89. See Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (Procedure for out-of-court settlement); Legal Services Authorities Act, 1987 (Establishment of Lok Adalat).

11. Mediation Act, 2023, Preamble; Commercial Courts Act, 2015.

12. Guidelines for Arbitration and Mediation in Contracts of Domestic Public Procurement, No. F. 1/2/2024-PPD.

13. Guidelines for Arbitration and Mediation in Contracts of Domestic Public Procurement, No. F. 1/2/2024-PPD.

14. Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024.

15. Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Bill, 2024.

16. Khaitan & Co, Arbitration Survey Report: Current Trends in Domestic Arbitration in India (2024)., available at:<Current Trends in Domestic Arbitration In India (khaitanco.com)> ; Khaitan & Co | India still has scope for improvement in Domestic Arbitration, available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/03/26/khaitan-co-india-still-has-scope-for-improvement-in-domestic-arbitration/

17. Khaitan & Co, Arbitration Survey Report: Current Trends in Domestic Arbitration in India (2024)., available at:<Current Trends in Domestic Arbitration In India (khaitanco.com)> ; Khaitan & Co | India still has scope for improvement in Domestic Arbitration, available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/03/26/khaitan-co-india-still-has-scope-for-improvement-in-domestic-arbitration/

18. PWC, Corporate Attitudes and Practices Towards Arbitration in India, <corporate-attributes-and-practices-towards-arbitration-in-india.pdf (pwc.in)>.

19. Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, S. 29-A.

20. Federation of Indian Corporate Lawyers (FICL) and Centre for Trade and Investment Law (CTIL), Survey of Dispute Resolution in India, 2023: Growth and Future of Alternate Dispute Resolution in India 31 (2023).

21. Madhav Goel et al., “Arbitration Realities: Patterns of Challenges and Judicial Responses”, IndiaCorpLaw ,available at: <Arbitration Realities: Patterns of Challenges and Judicial Responses — IndiaCorpLaw>.

22. Madhav Goel et al., “Arbitration Realities: Patterns of Challenges and Judicial Responses”, IndiaCorpLaw ,available at: <Arbitration Realities: Patterns of Challenges and Judicial Responses — IndiaCorpLaw>.

23. Federation of Indian Corporate Lawyers (FICL) and Centre for Trade and Investment Law (CTIL), Survey of Dispute Resolution in India, 2023: Growth and Future of Alternate Dispute Resolution in India 31 (2023).

24. Karnataka Mediation Centre, General Detail Statistical Report.

25. Chris Wise, “Mediation Versus Litigation: Pros and Cons”, Wise & Associates (28-8-2024, 2:7 p.m.) <https://www.wiseafl.com/blog-post/mediation-versus-litigation-pros-and-cons>.

26. Patil Automation (P) Ltd. v. Rakheja Engineers (P) Ltd., (2022) 10 SCC 1, para 53.

27. Mediation Act, 2023, S. 3(e).

28. Vikram Bakshi v. Sonia Khosla, (2014) 15 SCC 80, para 15.

29. Delhi High Court Mediation & Conciliation Centre, Real-Time Pendency.

30. Karnataka Mediation Centre, General Detail Statistical Report.

31. City Civil & Sessions Court, Mumbai, Statistical Reports.

32. Commercial Courts of West Bengal, Consolidated Data.

33. Patil Automation (P) Ltd. v. Rakheja Engineers (P) Ltd., (2022) 10 SCC 1, para 51.

34. Patil Automation (P) Ltd. v. Rakheja Engineers (P) Ltd., (2022) 10 SCC 1, 31.

35. State Bank of Hyderabad v. S.P. Savithri, 2005 SCC OnLine Mad 150, 278.

36. Mediation Act, 2023, Statement of Objects and Reasons.

37. Mediation Act, 2023, S. 5.

38. See jurisdictions like Australia; Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Strengthening Mediation in India (2016) <https://vidhilegalpolicy.in/wp- content/uploads/2019/05/26122016_StrengtheningMediationinIndia_FinalReport.pdf>.

39. International Mediation, Global Trends, Clifford Chance <https://www.cliffordchance.com/content/dam/cliffordchance/briefings/2013/03/international-mediation-global-trends.pdf> (last visited on 1-9-2024).

40. US vs UK ― A Comparison of Mediation Processes, Skuld <US vs UK – a comparison of mediation processes — Skuld> (last visited on 30-7-2024).

41. Relevance of Mediation to Justice Delivery in India, A Paper Presented by Justice M.M. Kumar, Judge, Punjab and Haryana High Court, Chandigarh, in the National Conference on Mediation, organised by the Mediation & Conciliation Project Committee, Supreme Court of India, held on 10-7-2010 at New Delhi <https://www.highcourtchd.gov.in/sub_pages/top_menu/about/events_files/NCMediationNewDelhi.pdf>.

42. Law Commission of India, Government and Public Sector Undertaking Litigation Policy and Strategies, Report No.126 (1988) <https://cdnbbsr.s3waas.gov.in/s3ca0daec69b5adc880fb464895726dbdf/uploads/2022/08/2022080866-1.pdf>.

43. IANS, “CJI Stresses Prominence of Mediation for Commercial Dispute Resolution”, Business Standard available at: <https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/cji-stresses-prominence-of-mediation-for-commercial-dispute-resolution-122031900627_1.html>.

44. Khaitan & Co, Arbitration Survey Report: Current Trends in Domestic Arbitration in India (2024)., available at:<Current Trends in Domestic Arbitration In India (khaitanco.com)> ; Khaitan & Co | India still has scope for improvement in Domestic Arbitration, available at: https://www.scconline.com/blog/post/2024/03/26/khaitan-co-india-still-has-scope-for-improvement-in-domestic-arbitration/