Early life

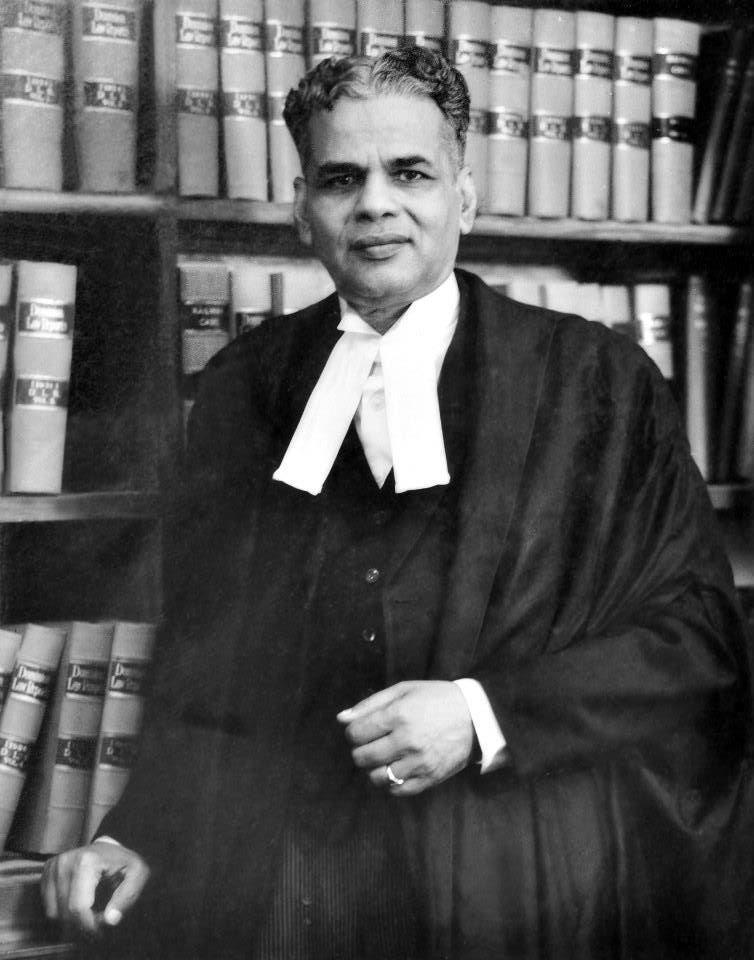

If the life and ways of Justice E.S. Venkataramiah are to be stated in a nutshell, the line that instantly comes to mind is one by Rudyard Kipling “if you can walk with Kings — nor lose the common touch”.1 E.S. Venkataramiah was born on 18-12-1924 in Manikyanahalli, a small hamlet in Karnataka. Born into a family of very modest means, his father was a teacher and tilled a small plot of land to augment his income whilst his mother cared for the family. His rise to hold the highest office in the Indian judiciary (also the first Chief Justice of India from Karnataka) from such ordinary circumstances, in the words of Prof. Gadbois, is a “compelling story”.2 His rise from such debilitating circumstances is a shining example that material poverty does not hinder any person when perseverance, urge for self-improvement, intellectual curiosity, moral values, and hard work are his/her constant companions. Venkataramiah was guided by these values which remained lodestars that lit the path of his meaningful but short life.

Venkataramiah had first-hand experience from his father’s role as a teacher regarding the transformative potential of formal education. For not only did it help his father earn a modest living but also transformed the lives of students he taught. Venkataramiah often fondly remembered the role of his mother, Smt Nanjamma, in inculcating in him the quest for knowledge and self-improvement and the ability to enjoy the sense of fulfilment imparted by the two, in addition to humility. Venkataramiah, who was hitherto assisting his father with odd jobs on the land he tilled, started his schooling at the age of six in the French Rocks Primary School at Pandavapura (then known as French Rocks). Thus, Venkataramiah became the first graduate and first lawyer in his family.

This early exposure to the pleasures of learning stayed with him for life and Venkataramiah always appreciated a good book, an intelligent conversation, and a good game of cricket (because it was a gentleman’s game). He was well-read and his impressive personal library bears testimony to this. He was also well-versed in Sanskrit and his insight into the nuances and beauty of the language are reflected in some of his judgments.3 Therefore Prof. Gadbois aptly refers to him as “a scholarly and an unassuming man…”.4

As a student of History, Economics, and Political Science at Maharaja’s College, Mysore, he graduated with a distinction in the Class of 1943 with gold medals in Political Science and Economics. The gold medals were received from the then Maharaja of Mysore His Highness Sri Jayachamarajendra Wadiyar. Reading for a law degree was not a natural choice since he did not come from a family of lawyers or Judges.5 He was also interested in Indian Railways and Economics. He enrolled for a year at Indian Law Society’s (ILS) Law College at Pune (which is the alma mater of Chief Justice Y.V. Chandrachud) and completed his law degree from Raja Lakhamgouda Law College, Belgaum by securing first class in the college (the first to secure a first class in the college and also the alma mater of many notable Judges, ministers, and lawyers).

Venkataramiah wanted to become a teacher like his father. Venkataramiah was always “a teacher at heart” observes Prof. Gadbois in his sketch.6 He taught at his alma mater Raja Lakhamgouda Law College soon after graduation as a fellow of Karnataka Law Society and before he started practice as an advocate in Bangalore. He also taught at National Law School of India University, Bangalore soon after he demitted office as Chief Justice of India. When asked by his student whether he enjoyed teaching more or being a Judge, he was quick to answer saying teaching bright young minds was more rewarding than his stint as an incumbent of the highest office in the judiciary.7

Stint at the Bar

Venkataramiah started practice in Bangalore in the office of Chief Justice Somnath Iyer (then a lawyer) who is a shining star in the galaxy of great Judges of the Mysore High Court. Under the able guidance and great personality of Justice Iyer, Venkataramiah could not have asked for a better role model. It is apt to mention that in the reference held for Justice Somnath Iyer on his passing, Acting Chief Justice M. Rama Jois recounts two valuable contributions of Justice Somnath Iyer to the Karnataka High Court, one of them being his junior Justice E.S. Venkataramiah and the other Justice Srinivasa Iyengar also his junior.8 At the young age of 21, Venkataramiah commenced practice as a Pleader in the subordinate courts on 2-6-1946 and thereafter on 5-6-1948 he enrolled as an Advocate of Mysore High Court.

Venkataramiah also practised in the chambers of Sri H. Srinivasa Murthy for a short while before he started his own chamber in 1947 which was within a year of his stint in the chambers of Justice Iyer and Sri H. Srinivasa Murthy. On 2-6-1966 he was appointed as Special Government Pleader and on 6-6-1969 as Government Advocate. In March 1970, he was appointed the State’s Advocate General. Sri S.G. Sundaraswamy speaking on the tenure of Venkataramiah as Advocate General had to say, “even in a short span of 3 months your advice has been of considerable value in handling several of the knotty problems of the State including the river waters”.9

Venkataramiah showed keen interest in civil trial work in the early years of his career. His capacity to marshal facts, attention to detail, clever cross- examination skills coupled with his sound knowledge of legal doctrine helped him establish a flourishing practice with a diverse clientele. He always advised young advocates to hone their trial advocacy skills and this remains the need of the hour even today. In fact, Chief Justice Subhoranjan Dasgupta of the Mysore High Court offered Venkataramiah the post of District Judge which he kindly declined to pursue his career as an advocate. With the framing of the Constitution and advent of writ jurisdiction in the High Court, Venkataramiah expanded his practice and appeared extensively in High Court too. His motto as an advocate was “intellectual honesty, personal morality, and eagerness to secure relief to the litigants as early as possible”.10

Venkataramiah owed a deep debt of gratitude to the Bangalore Bar as a young lawyer. In a speech delivered by him at a conference organised by Rajasthan Bar Association, he fondly recollects the support rendered by the Bangalore Bar to him by saying “I was not known to anybody in Bangalore Bar before I went there. Soon all the members of the Bar took interest in me and they were kind, sympathetic and helpful towards me and often acted as teachers to me. They put strength into my faltering steps and helped me grow in the Bar”.11

Even as a busy advocate, Venkataramiah showed keen interest in and always made time for academic pursuits. He was the editor of the Mysore Law Journal. As Secretary of the High Court Advocates Association, he was instrumental in building the collection of the Advocates Association Library. Venkataramiah was one of the people who founded BMS Law College and also served as its Professor and Principal. As a President of the Mysore State Commission of Jurists he served as Conference Secretary of the International Commission of Jurists meeting held in Bangkok in 1968. He was an active member of the Council of Management of the Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs and was Chairman of Karnataka’s Legal Aid and Advice Board from 1976 to 1979.

One of the significant contributions of Venkataramiah as a young lawyer was the founding of the Legal Aid Society in 1948, long before the system of legal aid was formalised. On account of his background and experience in material poverty and attendant suffering, he was quick to appreciate the need for assistance and access to justice to indigent and needy litigants. A case that was very close to his heart as an advocate was his engagement in a legal aid brief where he was successful in saving an innocent person from the gallows in the sensational Drayton murder case popularly known as Joker’s case.

The juniors and colleagues of Venkataramiah, namely, Late Justice S.G. Dodda Kale Gowda, Late Sri G.V. Shantharaju (Senior Advocate) and Barrister Vasudeva Reddy founded the chamber “KESVY” named after Justice S.G. Dodda Kale Gowda, Justice E.S. Venkataramiah (fondly called ESV by his contemporaries), and Barrister Vasudeva Reddy and which chamber closely follows the ideals set by them. Venkataramiah, as a lawyer and later on as Judge, was always eager to encourage a talented and hard-working young lawyer. In fact, he was the first to recognise the needs of a young lawyer and pay a stipend to junior colleagues in his chamber at Balepet, which was later adopted by other chambers.

As a Judge of the High Court and Supreme Court

On 25-6-1970, at the young age of forty-five, Venkataramiah was appointed to the Mysore High Court as an Additional Judge and was confirmed as a permanent Judge on 20-11-1970.

In his welcome address on the elevation of Justice Venkataramiah to the Mysore High Court, the then Advocate General Sri S.G. Sundaraswamy had this to say:

“Although practically unknown in Bangalore at that time and in spite of having no one in the profession to give you a start, by sheer hard work and study combined with native intelligence and social charm, you soon made great headway in the profession and acquired a large and lucrative practice … Your work as a lawyer, whether on the original side or appellate side was marked by a good grasp of the fundamentals, thoroughness in preparation, and clear presentation. You fought for the client, whether it be a private party or the State, with the full conviction in the righteousness of your cause.”12

Justice Venkataramiah has rendered several important decisions as a Judge of the Mysore High Court and some of them remain authoritative even to this date. In the interest of brevity, reference is made to the decision in A.K. Subbiah v. Karnataka Legislative Council13 which embodies his views on independence of the judiciary, separation of powers, free speech and dissent in a democracy, judicial review and activism. In this case a petition was instituted in public interest by two members of the State Legislature alleging that certain derogatory remarks were made on the floor of the House concerning the conduct of Judges. While dismissing the petition, Justice Venkataramiah held:

2. This case involves great constitutional principles touching parliamentary democracy and independence of the judiciary and hence requires a cautious approach. An independent judiciary, according to Sri S.R. Das Gupta, an illustrious Chief Justice of this Court, is a judiciary which consists of Judges who are independent of themselves. I have not come across a better definition of that expression. A Judge should not allow his judgment to be influenced by personal prejudice. He should not allow passion to overtake reason. Whatever may be the provocation, he should not transgress law and abandon justice. Reason is the element which distinguishes man from other creations of God and judicial restraint is the soul of administration of justice.

23. It is unfortunate that an occasion has arisen in this Court to hear a case of this nature. But at the same time the Court cannot take any action which interferes with the immunity which a member has been granted under Article 194(2)14 of the Constitution merely because what he may have said is in violation of Article 21115 of the Constitution. Was it not Voltaire who said like this: “I do not agree with you; but I will fight for upholding your right to disagree with me till the end of my life.” In the same spirit, this Court which has a special obligation to uphold the Constitution and the laws, upholds Article 194(2) of the Constitution and the immunity guaranteed to the members of the Legislature thereunder, leaving it to them to uphold Article 211 of the Constitution in their deliberations. I am of the view that no action is called for in this case. The petition is dismissed.

During the Emergency, in July 1975, Chief Justice Govinda Bhat along with Justice Venkataramiah stayed the transfer of Atal Behari Vajpayee (who later became the Prime Minister of India) from the jail in Bangalore to Belgaum on the ground that the petitioner had undergone surgery just a few days before and thus upheld the inalienable rights which are enjoyed by every person including an imprisoned citizen at a time when fundamental rights are suspended.16

Justice Venkataramiah was on the Bench of the Karnataka High Court for a little over eight years and thereafter he was elevated to the Supreme Court of India in March 1979, when he was fifty-four years and was fifth in seniority. On 18-6-1989, after serving as a Judge of the Supreme Court for nearly a decade, he became the nation’s nineteenth Chief Justice and the first Judge from Karnataka to be appointed to that office.17

The then Advocate General Sri R.N. Byra Reddy on the eve of the elevation of Justice Venkataramiah to the Supreme Court said:

“You have not been a Judge confined to any particular branch of law. You have functioned as a Judge dealing with almost all branches of law. In each branch you have rendered judgments of great distinction and you have left through your judgments an indelible mark on each one of the branches you have dealt with…. You are undoubtedly a man of deep learning not merely in law but in many fields of human knowledge. You are deeply aware of the conflicting values engaged in a grim battle in a changing society. You instinctively applied and adopted the values of life which did true justice to those who are in real need of it in a society in which injustice, inequality, and oppression abound. This was possible for you without any effort for the reason that the environment in which you were brought up enabled you to understand and appreciate the pangs of hunger and suffering of the oppressed…. Your intellect is scintillating and you have acquired for yourself great profundity of knowledge. But what is more remarkable in you is your ceaseless passion for more and more research into the fundamentals of the law and the basic legal concepts which arise for consideration in the case before you.”18

As a Judge of the Supreme Court, Justice Venkataramiah has rendered innumerable judgments touching upon various branches of law most of which continue to be good law even today. In the interest of brevity, I would like to touch upon a few significant decisions which portray his views on fundamental rights jurisprudence in particular and constitutional adjudication in general. The eminent Senior Advocate Sri Fali Nariman recounts Justice Venkataramiah as a Judge “from whom we all learnt and whom we all knew and loved”.19

Justice Venkataramiah seized the opportunity to showcase his keen legal acumen in the first few weeks as a Judge of the Supreme Court. This opportunity presented itself in the form of Needle Industries (India) Ltd. v. Needle Industries Newey (India) Holding Ltd.20. Although Justice Y.V. Chandrachud authored the judgment, the courtroom exchange spearheaded by Justice Venkataramiah culminated in a decision which is an authority on the doctrine of oppression and mismanagement in Company Law. It is one of the few Supreme Court decisions which has set out the framework on oppression and mismanagement and holds the field even to this date.

A significant reference order by Justice Venkataramiah is in A.R. Antulay v. R.S. Nayak21, involving the breach of fundamental rights of the accused persons by prescribing special procedure which departed from ordinary procedure to the prejudice of the accused. Deeply agitated by the extent of injustice and prejudice caused to the petitioner on account of special procedure, Justice Venkataramiah’s thundering statement in the court hall “if Article 14 was applicable to Anwar Ali Sarkar, why not to Abdul Rehaman Antulay?” culminated in a reference to a seven-Judge Bench to examine the extent to which special procedure prejudiced the accused/petitioner. This resulted in a decision with five Judges of the Supreme Court agreeing with the views expressed by Justice Venkataramiah in his reference order and is a landmark on special courts and special procedure for criminal trial. It is cited and relied upon even today in view of increasing number of legislations which mandate special procedure to try offences created therein.

Justice E.S. Venkataramiah’s opinion in K.C. Vasanth Kumar v. State of Karnataka22 reviewed the judicial dicta of the Supreme Court starting from M.R. Balaji v. State of Mysore23 to formulate a test of determine “backwardness” for the purpose of reservation. It is opined that Justice Venkataramiah, along with Justices Y.V. Chandrachud and O. Chinappa Reddy favoured the caste-cum-means test whilst Justices Sen and Desai favoured an exclusive economic criterion to determine backwardness.24

Decisions rendered by Justice E.S. Venkataramiah on the freedom of press laid the foundation for constitutional protection of free speech in India. In Indian Express Newspapers (Bombay) (P) Ltd. v. Union of India25 wherein the petitioner challenged imposition of customs duty on imported newsprint, Justice Venkataramiah speaking for the Bench opined that “freedom of press is the heart of social and political intercourse” and it is the duty of the press to be critical of the unpalatable actions of the Government to maintain openness and transparency in administration. These words remain true even today with several attacks on free speech and attempts to muzzle the press. In Odyssey Communications (P) Ltd. v. Lokvidayan Sanghatana26, the right to telecast was recognised as a facet of Article 19(1)(a)27.

Justice E.S. Venkataramiah in Mackinnon Mackenzie & Co. Ltd. v. Audrey D’Costa28 held that differential pay scales for female and male stenographers was against the right to equality enshrined in the Constitution and the principle of equal pay for equal work. Whilst opining so the Supreme Court for the first time recognised the enforceability of the said principle thereby overturning the prevailing view that such a right is not enforceable.29

Justice E.S. Venkataramiah was part of the Bench that directed the State, in a petition by noted activist Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, to house children rounded up in indiscriminate arrests in Punjab during Operation Blue Star, in better conditions and in special institutions.30

Justice Venkataramiah in M.C. Mehta v. Union of India31 ordered closure of all the tanneries on the banks of Ganges in Kanpur to ensure that effluents are not discharged into the Ganges river. This is also a significant case in the series of cases on Ganga Action Plan and in recognising third generation rights such as right to clean environment. Justice Venkataramiah lamented the fact that—

7. although Parliament and the State Legislatures have enacted the laws imposing duties on Central and State Boards and municipalities for prevention and control of pollution of water, many of these powers have remained on paper.

Whilst holding a midnight hearing at his official residence to consider the bail plea of Lalith Mohan Thapar, Justice Venkataramiah said “if I feel that injustice has been done, there is nothing in the world that can come between me and him (one who is wronged) to grant appropriate relief”32 in response to the criticism of many who termed this hearing as “midnight judiciary”.

Justice Venkataramiah’s separate opinion in S.P. Gupta v. Union of India33, popularly known as the First Judges’ Case remains one of the longest concurring opinions by a Supreme Court Judge34 and was significant for critically balancing the views of the differing Judges on the system of judicial appointments.

In Ishwar Chand Jain v. High Court of Punjab & Haryana35, whilst opining on the nature of relations between the High Court and subordinate courts as per the constitutional scheme, he held—

14. While exercising that control it is under a constitutional obligation to guide and protect judicial officers…. An independent and honest judiciary is a sine qua non for rule of law. If judicial officers are under constant threat of complaint and enquiry on trifling matters and if High Court encourages anonymous complaints to hold the field the subordinate judiciary will not be able to administer justice in an independent and honest manner. It is therefore imperative that the High Court should also take steps to protect its honest officers by ignoring ill-conceived or motivated complaints made by the unscrupulous lawyers and litigants.

Sometime in 1989, six cricketers of India including Kapil Dev, Ravi Shastri, and Azharuddin suffered a six-year ban imposed by Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) for having played some matches without permission of BCCI after the West Indies tour. Two young advocates and ardent cricket fans, K.N. Bhat and Mukul Mudgal (who later became Justice Mukul Mudgal and retired as Chief Justice of Punjab & Haryana High Court) moved a petition styled as a public interest litigation questioning the ban. This was at a time when both public interest litigation and “sports law” were at its nascent stage. The matter came up for hearing before Justice Venkataramiah who was then the Chief Justice of India. Mr K.N. Bhat recalls “at the very first hearing, without going into the technicalities, the Chief Justice of India (CJI) observed: ‘Let us hear the BCCI.’ A day or two later, the BCCI appeared and without waiting for any formal order lifted the ban order unconditionally. Thus ended the misery of the six players and a ‘would have been’ sad chapter in the cricketing history of India.”36

Justice Venkataramiah repeatedly emphasised on clearing backlog of cases. He suggested appointment of retired Judges as ad hoc Judges to reduce arrears. Immediately on the elevation of Justice Venkataramiah as Chief Justice of India, he addressed letters to Chief Ministers and Chief Justices to consider various proposals to reduce pendency. During his tenure as Chief Justice, Venkataramiah appointed six Judges to the Supreme Court including Justice Fathima Beevi, the first woman Judge of the Supreme Court.

As a Judge of the Supreme Court, Venkataramiah was given several assignments. He chaired a Commission to determine which Hindi speaking areas of Punjab should be given to Haryana for Punjab keeping Chandigarh. He was president of the Supreme Court’s Legal Aid Committee in which capacity he encouraged many young lawyers to advocate the cause of poor and downtrodden and those in need of access to justice. He served as chairman of the Committee to select the president of Central Excise and Revenue Tribunal; Chairman of Citizen Development Society, and president of Indian Law Institute.

Post-retirement life

After retirement, Justice Venkataramiah held M.K. Nambiar Constitutional Law Chair at the National Law School of India University in Bangalore. He also served as Chairman of many institutions in Bangalore such as Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Sri Aurobindo Society, the Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC) and Savodaya International Trust. He was elected as the first President of the Indian branch of the International Institute of Human Rights at New Delhi.

Justice Venkataramiah authored several books and delivered speeches and lectures on a variety of topics. Some of the lectures are “Women and Law” (Banaras Hindu University, 1985); and “A Free and Balanced Press” (TRF Institute for Social Sciences Research and Education, 1986); “Freedom of Press: Some Recent Trends” (Endowment Lecture at Advocates Association, Bangalore, 1988); “The Parliamentary Privileges and Courts” (Orientation Seminar for New Members of Karnataka Legislative Assembly, 1990); Thanka Memorial Lecture on “Citizenship: Rights and Duties” (Jabalpur) to name a few. Justice Venkataramiah was also invited to be a member of the Board of Advisors to the Reserve Bank of India which he accepted. He was also the chairman of a Committee which suggested amendments to the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 195437 and was a director on the board of Pioneer Newspapers. He advised the Karnataka Government on the Cauvery river dispute38.

Books authored by him include: B.N. Rau, Constitutional Adviser (N.M. Tripathi Pvt. Ltd., Bombay, 1987); and Citizenship, Rights and Duties. He co-authored with P.M. Bakshi a book titled Indian Federalism: A Comparative Study. Justice Imperiled is a memoir authored by him and published in 1992 which recounts one of the important cases of the Mysore High Court involving the supersession of the Chief Justice and a senior Judge of the Mysore High Court at the dawn of coming into force of the Constitution of India. The memoir touches upon aspects of judicial independence and relations between the executive and judiciary. It is a first-hand account of the said events which he keenly followed as a young lawyer and was penned after his retirement upon studying various documents of that period. He was the editor of Human Rights in a Changing World (New Delhi: Regional Branch of the International Law Association, 1988). Justice Venkataramiah wrote op-eds on various subjects like “Article 356-A: A Case for Repeal”; “Reservation for Women in Legislation”, etc. to name a few.

Several honours were conferred on Justice Venkataramiah for his contribution to the legal field. He was conferred with an honorary doctorate by Karnatak University and Acharya Nagarjuna University. He was also honoured with the Rajyotsava Award by the State of Karnataka in 1996.

Whilst these post-retirement engagements kept him busy, Venkataramiah passed away early. He wanted it that way: to pass to the next life when he was at the pinnacle of this one, and that was not when he was on the Bench but after retirement on having attained the stature of an honest and true public intellectual.39 He was a true karma yogi in all that he achieved and also practiced Nishkama Karma for he often repeated that he had no attachments nor expectations from his actions and was always ready to embrace the passage from this life to the next.

Conclusion

Recalling the words of Justice Y.V. Chandrachud on Justice E.S. Venkataramiah:

“The Constitution spoke directly to him as a person, a Judge, and an Indian citizen. He conceived of the Constitution as an embodiment of values that he believed in and as a basis of granting him, as a Judge, power to protect those values. He repeatedly emphasised that he had a “duty” under the Constitution to see that his understanding of its imperatives was implemented, and he saw the Constitution’s imperatives as basically ethical in nature. Those imperatives that he read into the Constitution were so clear to him, and his duty to implement them so transparent, that matters of doctrinal interpretation and of institutional power became nearly irrelevant to him. That is why, his erudition was unspoken and not perceptible to the passerby.”

He further adds:

“Indeed, he felt bound, as a Judge, to consider ethical imperatives in his adjudication. In his view, they deserved as much consideration as explicit constitutional language and perhaps more. His principal concerns as a Judge were to discern the underlying ethical structure of the Constitution and to apply rigorously its ethical imperatives, even if such an application resulted in a failure to achieve orthodox doctrinal consistency. He did not pride himself either as an oracle or as an orator…. In the now emerging public world of corruptible and self- serving persons, he set a standard of incorruptibility and humanity.”

It is hoped that the life and values of Justice E.S. Venkataramiah will continue to be a source of hope and inspiration for one and all to attain greater glory.

*BA, LLB (Hons.); BCL (Oxon), Advocate practising in Bangalore. Author can be reached at: nayanatara.bg@gmail.com.

1. “If” by Rudyard Kipling.

2. George H. Gadbois Jr., Judges of the Supreme Court of India, (Oxford University Press) pp. 274-277 .

3. See, Opinion of Justice Venkataramiah on interpretation of Smritis and commentaries on Hindu law on the practice of putrika putra in Shyam Sunder Prasad Singh v. State of Bihar, 1980 Supp SCC 720.

4. George H. Gadbois Jr., Judges of the Supreme Court of India, (Oxford University Press) p. 274.

5. The “Archetypal Judge” according to Gadbois is a son of a lawyer born into a family where the practice of law has been tradition for generations and born into a wealthy or upper middle- class family. Venkataramiah met neither of these two criteria. See George H. Gadbois Jr., Judges of the Supreme Court of India, (Oxford University Press) pp. 378-377.

6. George H. Gadbois Jr., Judges of the Supreme Court of India, (Oxford University Press) p. 276.

7. From his private collection of letters.

8. M. Rama Jois, Acting C.J., Reference held for Justice Somnath Iyer on his passing, ILR 1991 (4) Kar 40.

9. (1970) 2 MLJ 1.

10. AIR 1984 Raj 129 (Journal Section).

11. AIR 1984 Raj 129 (Journal Section).

12. (1970) 2 MLJ 1.

14. Constitution of India, Art. 194(2).

15. Constitution of India, Art. 211.

16. Atal Behari Vajpayee v. Union of India, W.P. 3318/1975. See also, M. Rama Jois, (M.R. Vimala, Bangalore, 1977), pp. 15-16

17. Justice E.S. Venkataramiah was administered oath of office by the then President of India Sri. R Venkatraman. It is said that Justice E.S. Venkataramiah and Sri R Venkataraman were travelling by the same train to Nagpur as young lawyers to attend the All India Lawyers Conference in 1948. They exchanged courtesies as fellow passengers and lawyers in the same railway compartment who were attending the same event. Four decades later when they met in Rashtrapati Bhavan for the swearing-in ceremony of Justice E.S. Venkataramiah, the chance encounter in the train was still fresh in both their memories.

18. (1979) 1 KLJ 1-4.

19. Fali S. Nariman, God Save the Hon’ble Supreme Court, (Hay House, 2018) p. 284.

24. E.S. Indiresh, “A Critical Study of Justice E.S. Venkatramiah’s Contribution Towards Indian Constitutional Development”, LL.M. Dissertation (University of Mysore, 1997).

27. Constitution of India, Art. 19(1)(a).

29. Kishori Mohanlal Bakshi v. Union of India, 1961 SCC OnLine SC 230.

30. Gobind Thukral, “Operation Bluestar Victims: Children Continue to be Locked up in Dingy Jails in Punjab”, India Today (www.indiatoday.in, 30-9-1984).

32. “First Post — Midnight Hearing in Supreme Court’s Annals” (www.moneylife.in).

34. George H. Gadbois Jr., Judges of the Supreme Court of India, (Oxford University Press) p. 276.

35. (1988) 3 SCC 370, 381-382.

36. K.N. Bhat, “Lodha Panel can’t Run Indian Cricket” (www.deccanchronicle.com).

37. Prevention of Food Adulteration Act, 1954.

38. State of Karnataka v. State of T.N., (2018) 4 SCC 1.

39. Justice E.S. Venkataramiah was seventy-two when he died on 24-9-1997.

A well researched and apt article of a great man.

An inspiration to the young achievers