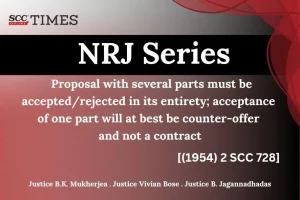

Supreme Court: In an appeal wherein, the issue for consideration was whether a concluded contract was arrived at between the parties, the three-Judges Bench of B.K. Mukherjea, Vivian Bose* and B. Jagannadhadas, JJ., observed that there was more in the proposals than Para A and the three options, which was acknowledged by the appellants. The Supreme Court stated that it was beyond dispute that if a proposal contained Items A, B and C (which must be accepted, or rejected in their entirety) and out of them, Para A conferred rights and privileges on the party to whom the offer was made while B and C imposed obligations and liabilities, then, if the other side stated “I accept your offer contained in A” there was no contract. It would, at best, a counter-offer.

Thus, the Supreme Court agreed with the High Court and stated that there was no ambiguity and could not look at the subsequent correspondence and conduct of the parties.

Background

In the present case, the appellants were a father and two sons. The respondents were also a father and two sons. Respondents 4 and 5 were the respective wives of the two sons on the respondents’ side. The two fathers entered into a partnership and carried on business at Bombay, Calcutta, Madras and Karachi as iron and hardware merchants under the name and style of Murlimal Santram & Co. In March 1947 the four sons were admitted to the partnership, each side again having equal shares. This was called as the partnership firm.

In 1948, the three appellants and Respondent 1, his son, Respondent 2 and this son’s wife, and one R.V. Joshi formed a private limited company called Murlimal Santram & Co., (Bombay) (‘Bombay Company’). This company bought and took over all the stock-in-trade of the partnership firm in Bombay.

In 1949, a similar limited company consisting of the Appellants 1, 2 and Respondent 1 and his son, Respondent 3 and this son’s wife, Respondent 5, was formed at Madras. It was called Murlimal Santram & Co. (Madras) (‘Madras Company’). In 1950, a similar private limited company was started in Calcutta, with the name Murlimal Santram & Co. (Calcutta) (‘Calcutta Company’). It consisted of the Appellants 1, 3 and Respondents 1, 2 and 4.

As a result of the various transactions, the partnership firm ceased to do business, but it remained in being and owned several properties and indeed continued to purchase properties down to the year 1951. In January 1951, disputes arose between the partners in the partnership firm, so they decided to wind up the partnership and dissolve it.

The appellants’ case was that the negotiations about this culminated in the respondents making appellants certain offer on 22-1-1951. The appellants stated that they accepted this offer by a telegram and letter dated 23-1-1951 and that thereupon a contract sprang into being. It was this contract which the appellants seek to enforce in this suit. The only question which had so far been tried was a preliminary question whether there was a concluded contract. The appellants said “Yes” and the respondents said “No”. Both the lower courts agree with the respondents. Hence, the present appeal. The issue in the present case was whether a concluded contract was arrived at between the parties.

Analysis, Law, and Decision

The Supreme Court observed that there was more in the proposals than Para A and the three options. There were the conditions in the preamble. Then there was, Para B and there were further conditions set out in the “Further Clarification” part of the document. The Supreme Court stated that it was beyond dispute that if a proposal contained Items A, B and C (which must be accepted, or rejected in their entirety) and out of them, Para A conferred rights and privileges on the party to whom the offer was made while B and C imposed obligations and liabilities, then, if the other side stated “I accept your offer contained in A” there was no contract. Thus, it would, at best, a counter-offer.

The Supreme Court observed that the appellants relied very strongly on the concluding words of the acceptance, which stated that, “as we have accepted your proposal the concluded contract has now resulted. Please therefore see that the terms of this contract are carried out.” The Supreme Court stated that a contract could not arise simply because one party chooses to say that it had.

The Supreme Court stated that passage relied on by the appellants, could not be read apart from the preceding passages which qualify its more general terms, and there, the stress throughout was on Para A alone on the “Property side” and on the three options on the “Cash side”. Para B was ignored, the “Further clarification” was ignored and so was the preamble.

Thus, the Supreme Court agreed with the High Court and stated that there was no ambiguity and could not look at the subsequent correspondence and conduct of the parties.

[Kishandas Murlimal v. Doongermal Bachumal Futnani, (1954) 2 SCC 728, decided on 22-09-1954]

*Judgment authored by: Justice Vivian Bose

Advocates who appeared in this case :

For the Appellants: P.R. Das, Dr Bakshi Tek Chand, M.V. Desai and A.K. Sen, Senior Advocates (Rajinder Narain, Advocate, with them)

For the Respondents: M.C. Setalvad, Attorney General for India, C.K. Daphtary, Solicitor General of India (M/s Praful N. Bhagwati and I.N. Shroff, Advocates, with them)

**Note: What constitutes a contract

Section 2(h) of the Contract Act, 1872 (‘the Act’) defines the term contract. As per the provision, a contract is an agreement enforceable by law. Section 10 of the Act provides for what agreements are contracts. The provision states that all agreements are contracts, if they are made by the free consent of parties competent to contract, for a lawful consideration and with a lawful object, and are not hereby expressly declared to be void. In Union of India v. Bhim Sen Walaiti Ram, (1969) 3 SCC 146, it was held that

“an acceptance of an offer may be either absolute or conditional. If the acceptance is conditional the offer can be withdrawn at any moment until absolute acceptance has taken place.”

Further, in Food Corporation of India v. Ram Kesh Yadav, (2007) 9 SCC 531, it was held that

“when an offer is conditional, the offeree has the choice of either accepting the conditional offer, or rejecting the conditional offer, or making a counter-offer. But what the offeree cannot do, when an offer is conditional, is to accept a part of the offer which results in performance by the offeror and then reject the condition subject to which the offer is made.”