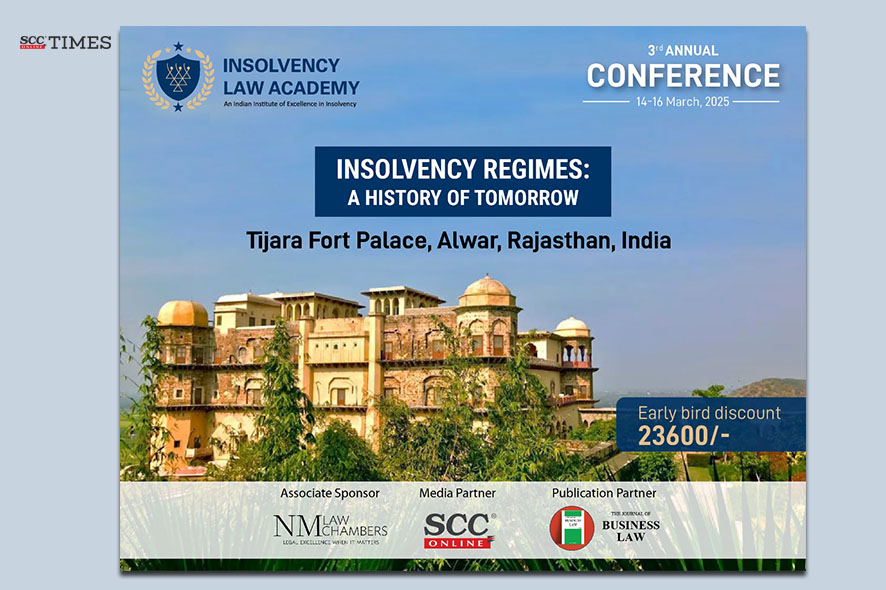

The Third Edition of the Insolvency Law Academy’s Annual Conference, consisting of the 3rd meeting of ILA’s Insolvency Scholars Forum and the 2nd meeting of ILA’s Emerging Scholars Group, is happening from 14th-16th March at Tijara Fort, Alwar.

The theme of ILA 2025 Conference is ‘Insolvency Regimes: A History of Tomorrow’.

ILA completes 3 years since it was established in June 2022. It has made long strides in this short period, creating impressionable global footprints. In his short presentation, the ILA President will provide a snapshot of all the key milestones, works in the pipeline, and focus areas for future.

DAY ONE [14th March 2025]

Opening Session:

Mr Sumant Batra, Insolvency Lawyer, President, Insolvency Law Academy, welcomes the delegates of ILA Conference at Tijara Fort, Alwar. Mr Batra shares vision of Mr Arun Jaitley, and the Arun Jaitly Mediation Centre; Bankruptcy Law Reforms Committee (‘BLRC’) – revolution; base for IBC in 2016; and INSOL.

Mr Batra also throws light on ILA first Emeritus Fellowship and how Bibek Oberio, a well-known economist and ILA was started in his office room.

The conference started with the special address by Justice Rakesh Kumar Jain, Judicial Member, National Company Law Appellate Tribunal, wherein he spoke about threshold increase from 1 lakh to 1 crore within 4 years. He further emphasised on there being only 5 benches of NCLAT and the need for upgradation of infrastructure as the need of the day. He also highlighted that the employees of NCLT and NCLAT were not permanent.

The keynote address was delivered by Dr. Krishnamurthy V. Subramanian, Executive Director, International Monetary Fund, USA and former Chief Economic Advisor, Government of India. In his address, he elaborates upon the relationship between inflation, currency depreciation and growth in India as well as globally. He also underscores how and why the rate of inflation in India has declined and consequently, so has the rate of rupee depreciation which makes India a destination of choice for international investors. Mr. Subramanian also spoke in depth about the Indian growth story which has taken place through reforms including the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (‘IBC’).

“Our international lawyer friends will go and communicate to their clients that in the next 25 years, there is no other country that can deliver 12% dollar growth, which India can. Therefore, India is basically, the destination, has to be the destination of choice for investors in the next 20-25 years.”

“I expect India’s GDP in nominal dollar to multiply about 16 times over the next 25-year period, less than the, you know, the Japanese or the Chinese experience, but still substantially.”

“India has grown, you know, from a few hundred billion dollars that we were in 1991 to about three and a half trillion now at 7% of the average.”

Mr. Dinkar Venkatasubramanian, Vice President Designate, INSOL International; President, INSOL India, in his special address spoke about the stressed asset perspective and also, emphasised on India’s position on it being imperative to sustain the level of growth. He also focused on turnaround and restructuring efore reaching the stage of insolvency. He highlighted the need for more trust between stakeholders involved in the IBC process.

Session 1: Insolvency Regimes: Looking Through the Rearview and the Windshield

Insolvency laws have gone through a series of transformation ever since the process of modernisation began in the early 20th century. Economic, social, and global events have shaped the journey of insolvency reforms. Many institutions have worked with policymakers and experts to make insolvency systems robust to minimise the shocks of global and national events, and to make insolvency reforms efficient and effective even otherwise. The world has come a long way since the exercise for standard setting and global benchmarking of insolvency systems started. Although, many efforts have been made to keep pace with the rapid global developments, it is always the effort of experts to keep a close watch on the preparedness of the insolvency systems to deal with crisis and changing times. In this backdrop, this session, a distinguished panel of experts from around the world will discuss the key developments that have taken place in the last few decades, their relevance in the present times and adjustments that may be necessary to keep the insolvency reforms relevant and impactful to meet the changing times.

The panel consists of Mr. James H.M. Sprayregen, Vice Chairman, Hilco Global, USA; Ms. Antonia Menezes, Senior Financial Sector Specialist, World Bank Group, USA; Prof. Dr. Reinout D., Professor of Insolvency Law, Leiden Law School, Leiden University, Netherlands; Mr. Dinkar Venkatasubramanian, Vice President Designate, INSOL International and President, INSOL India; and Ms. Pooja Mahajan, Partner, Chandhiok & Mahajan, Advocates and Solicitors, as the moderator.

Ms. Antonia Menezes discusses the importance of understanding both current and future solvency trends by first considering broader financial sector developments. According to the World Bank’s Financial Prospects Report from January 2025, while some of the findings may already be outdated due to market disruptions, the report provides a solid foundation.

She stated that or instance, the report notes that domestic credit to the private sector by banks, as a percentage of GDP, averaged 42% in emerging markets in 2023 compared to 96% in advanced economies. Additionally, bank lending to deposits growth—an indicator of financial system resilience—averaged about 8 percentage points in emerging markets between 2019 and 2023, compared to just 3 percentage points in advanced economies. Globally, growth is expected to hold steady at 2.7% between 2025 and 2026. In the context of rapid credit growth, financial regulators have been urged to monitor and protect against threats to financial stability.

Furthermore, she added that looking at other sources, an RBI report indicated that household debt in India stood at 42.9% of GDP in 2024. Moreover, data from 34 economies showed that new business insolvency cases increased by 33% from 2022 to 2024, including a 12% increase between 2023 and 2024. In terms of insolvency recovery rates, 4% of lower-income countries, 24% of lower-middle-income countries, and 46% of upper-middle-income countries reported recovery rates at or above the global average of 37 cents on the dollar. Notably, fewer than 20% of economies offer robust options to address the early onset of financial distress.

In this context, Ms. Menezes highlights two major trends. First, the rising consumer debt levels have spurred greater focus on personal insolvency frameworks. Countries are increasingly aiming to reduce the stigma associated with bankruptcy and allow individuals to make a fresh start. This shift has been supported by tools and frameworks that enable consumers to engage with banks early in the insolvency process. The World Bank has been active in this area, working on tools to assist consumers in negotiating with creditors and supporting fair debt collection practices. Furthermore, in common law countries like India, small unincorporated firms (such as those in the informal sector) are subject to personal insolvency frameworks, making it critical to provide them with tools to navigate financial distress.

Second, Ms. Menezes addresses the growing role of technology and digitalization in insolvency processes. Globally, there is an increasing emphasis on data collection and automation, not just within institutions like courts and regulators, but also among insolvency practitioners. India’s digitization of its liquidation process is presented as a leading example of how technology can streamline insolvency proceedings. Additionally, there is an increasing focus on the risks associated with digital assets, such as mobile money funds, and how insolvency practitioners can identify and realize value from these assets. The World Bank is exploring the potential risks digital assets pose in insolvency proceedings.

She also references the World Economic Forum’s “Future of Jobs” report from January 2025, which predicts that the highest-demand skills of the 2020s will include AI, big data, creative thinking, and technological literacy. These skills will increasingly impact professions like insolvency practice, influencing both business failures and the broader market trends.

Ms. Menezes concludes by stating that the landscape of insolvency is evolving, driven by rising consumer debt, the digitalization of processes, and technological advancements. These trends will continue to shape the future of financial distress resolution and insolvency frameworks worldwide.

Mr. James H.M. Sprayregen discussed several significant trends in the restructuring and bankruptcy landscape, particularly from a U.S. perspective, following the introduction by Ms. Menezes. He begins by acknowledging the academic community, particularly the connection with the National University of Singapore, and encourages students and members to reach out for further discussions on commercial opportunities and resources available through the program.

Mr. Sprayregen then shifts focus to the current trends within restructuring and bankruptcy processes. He emphasizes that one of the most notable developments in the U.S. has been the dramatic increase in the cost of going through a restructuring or bankruptcy. This rise in costs has led to shifts in how companies approach these processes, with significant changes in both strategy and conduct. While the increased costs are necessary in some cases, they have undeniably become a larger proportion of the overall financial situation, prompting adjustments in how cases are handled.

He points out that the cost issue has driven efforts to formalize and streamline the process. In the U.S., LD (Liability Management) Exercises have emerged as a popular alternative in larger and mid-sized cases. These exercises, designed to manage liabilities without undergoing the full formal bankruptcy process, have become more common in recent years. Mr. Sprayregen notes that although these exercises are often informal and less costly, they have been associated with a significant portion of defaults in recent years, even though these defaults typically involve targets or specific liabilities. This trend is gaining traction not just in the U.S., but is also starting to spread to other jurisdictions, though it has not yet seen widespread implementation in countries like India.

Another important development, he highlights, was the rise of prepackaged bankruptcy procedures, which focus on speed to reduce costs. While the focus on speed helps keep costs down, he cautions that such quick resolutions might not always allow for the depth and thoroughness of a formal restructuring process, which could be essential in some complex cases.

Mr. Sprayregen also points out the growth of the Small Business Chapter 11, which was introduced in the U.S. before the COVID-19 pandemic. The chapter was designed to streamline the restructuring process for small businesses, which were previously forced to use the same Chapter 11 process as large corporations. The Small Business Chapter 11 has proven to be much more cost-effective and functional for smaller firms, though it was temporarily sunsetted after the pandemic. Despite this, Mr. Sprayregen indicates that a substantial portion of reorganization cases in the U.S. still rely on this process, making it an important tool for small businesses seeking an efficient and affordable solution to financial distress.

Beyond traditional restructuring mechanisms, he also highlights the increasing role of technology disruption in driving financial distress. As industries across the globe continue to undergo digital transformations, companies that fail to adapt to new technological advancements or business models are increasingly finding themselves facing insolvency. This disruption, he notes, is a growing factor that shapes the timing and causes of business failures, making it a significant trend in the restructuring and bankruptcy space.

Another key trend discussed by Sprayregen was jurisdictional competition. He mentions how companies are increasingly choosing to file for bankruptcy or restructuring in jurisdictions perceived to be more favourable, such as Singapore, the U.S., and the U.K. This competition, he argues, has ultimately proven to be beneficial, driving innovation and improvement in bankruptcy law across borders. COVID-19, in particular, highlighted the need for a more flexible, adaptive approach to restructuring, which has led to the global shift towards rescue and reorganization cultures, as opposed to liquidation-focused cultures.

Finally, he emphasises on the importance of recognizing each country’s socio-political and economic context when adopting elements of foreign insolvency systems. He points out that while the U.K. insolvency system may work well within the U.K., simply transplanting that system into another country without taking local circumstances into account can be problematic. Thus, he underscores the need for sensitivity to these local realities when adapting international restructuring practices.

In conclusion, Mr. Sprayregen’s insights on the evolving trends in restructuring and bankruptcy underscored the rising costs of these processes, the growing preference for informal and expedited procedures, and the increasing influence of technology disruption. He also highlighted the role of jurisdictional competition in shaping global bankruptcy law and emphasized the importance of adapting systems to fit local contexts.

Mr. Dinkar Venkatasubramanian discusses several important trends in the evolving insolvency regime, focusing on changes in the power dynamics, the need for faster and more efficient processes, and ongoing reforms. He emphasises the substantial shift in the insolvency process, particularly the transfer of power from the Board of Directors to the Committee of Creditors (CoC). Previously, the board had more control, but with the new system, the CoC has taken charge of managing the business during the insolvency resolution process. This shift allows for more effective management, with the CoC being tasked with finding a resolution within a designated time frame of 180 to 270 days.

From a regulatory perspective, the central bank and other authorities have supported these changes, acknowledging the need for a more streamlined process. However, there remains ongoing debate about how to make the insolvency process more efficient and avoid prolonged legal procedures. Mr. Dinkar points out that feedback from businesses is crucial for refining the system, and there are active discussions on how to ensure that the process can be completed more quickly, without unnecessary delays.

A key focus of these discussions has been the role of mediation in the insolvency framework. There is an ongoing effort to determine how mediation can be effectively integrated into the process, offering businesses an alternative to the full legal procedure. This would provide a more flexible and collaborative option, potentially saving both time and resources for companies that are able to resolve their issues amicably.

Mr. Dinkar also discusses the introduction of a phase one and phase two approach to insolvency cases. Under this new system, a portal has been created where stakeholders can access information and manage cases more efficiently. The approach is designed to expedite the process, offering different pathways depending on the complexity of the case. For smaller businesses, this system allows for faster resolution, which is intended to prevent unnecessary delays.

In India, reforms have been particularly focused on improving the insolvency process for small businesses. Over the past five years, stakeholders have come together to make the process more accessible for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). These reforms have been crucial in allowing SMEs to restructure more effectively without facing exorbitant costs. As a result, restructuring efforts have become more successful and efficient, with stakeholders working collaboratively to resolve issues more effectively.

At a broader level, Dinkar highlights the growing complexity of financial instruments in distressed situations. The handling of these instruments has become more difficult, and there is an increasing focus on simplifying and clarifying the management of such instruments during insolvency.

DAY TWO [15th March 2025]

Session 2: Reimagining BLRC After a Decade

The Bankruptcy Law Reforms Committee was set up in 2014 to recommend reforms in the Indian insolvency law. BLRC submitted this report in 2015, which culminated in the enactment of Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code in 2016. The BLRC was tasked to review the then existing framework and propose a comprehensive framework for the new insolvency law. The state of the economy and many other factors, global and national, have changed significantly since 2014. We now also have the benefits of lessons and experiences of implementation of IBC over almost 9 years. India aspires to become a developed country by 2047. Is it time to have BLRC 2.0 to have developments of last 10 years and look at futuristic vision of the country and recommend reforms in insolvency law to complement national aspirations? This distinguished panel will reflect on the journey of the last close to 9 years and the way forward.

This panel consists of Ms. Shreesha Merla, Hon’ble Former Member Technical, National Company Law Appellate Tribunal as the Chair, speakers namely, Mr. Sumant Batra; Anita Shah Akella, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India; Ms. Aparna Ravi, Partner, S&R Associates, India; and moderator Ms. Saloni Thakkar, Partner, AZB & Partners, India.

Ms. Aparna Ravi reflects on the development of the IBC, discussing the objectives set in 2014 and how the outcomes have evolved over time. She notes that during that period, the financial and regulatory landscape was vastly different, particularly in the banking sector. Public sector banks were facing significant stress, and the existing legal framework was inadequate for dealing with distressed assets. Laws such as the Sick Industrial Companies Act (SICA), 1985, were failing to provide effective solutions, as they allowed companies to hide assets and delay meaningful resolutions. As a result, the resolution of distressed assets was a prolonged process, and the legal system was unable to keep pace with the challenges of the industry.

Context for the NRC’s Objectives: In light of these challenges, the National Legal Reforms Committee (‘NRC’) set out three primary objectives for the creation of the IBC, namely, Timely Resolution, Maximizing Asset Value, and Encouraging Credit Extension.

Features of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC): When the IBC was finalized, it incorporated several features to address these objectives:

- The process was designed to be fast and efficient, with minimal judicial involvement. While the courts would oversee the process to ensure compliance, the resolution itself was intended to be driven by market participants.

- Professional involvement became a cornerstone of the IBC, with experts playing a pivotal role in resolving distressed assets, as opposed to relying on bureaucratic or judicial control.

- The resolution process was made flexible, allowing companies to either be restructured or integrated into other firms, depending on the circumstances. This flexibility was intended to be guided by market forces rather than rigid legal prescriptions.

-

The law also aimed to protect creditors from undue losses, ensuring that repayment issues were addressed in a fair and structured manner during the resolution process.

Initial Skepticism and Outcome: Ms Aparna admits that when the IBC was first implemented in 2016, there was skepticism about its effectiveness. Questions arose as to whether it would be able to resolve distressed assets as quickly as promised. However, looking at the results now, Aparna observes that the IBC has largely succeeded in achieving its goals. The legal framework has been effective in bringing in professionals who have managed to implement the process efficiently. Turnaround times have improved significantly compared to the situation before 2016, and there are signs of development in the markets, particularly in debt financing and the bond markets.

Ms. Shreesha Merla emphasises that a critical component of the transformation in insolvency and bankruptcy laws is the establishment of a robust and efficient framework. She notes that such a framework is essential for fostering intellectual confidence, resolving distressed assets, and ensuring clarity throughout the process.

According to her, the primary objective of the system should focus on creating a creditors-centric approach to insolvency resolution and restructuring. She highlights the importance of sections like Section 7 and Section 9, which allow applications to initiate insolvency proceedings. These two sections currently constitute 32% of insolvency applications within the system.

However, Ms. Merla expresses concern that despite the existence of these legal provisions, the outcomes of these operations have often been disappointing. Many cases are resolved only to a limited extent, which calls for a re-evaluation of the mechanisms in place. She stresses that the information revolution and a more professional approach are essential for improving the system. Additionally, professionals handling insolvency cases need to be properly trained to deal with these complex matters effectively. She also points out the significant burden on the professionals involved, suggesting that they should be adequately compensated for their work, as they often do not receive the fees they deserve, and there is a widespread perception that their contributions are undervalued within the system.

Another major issue she raises was the insufficient number of benches to handle insolvency cases across India. She gives the example of Delhi, which has only one bench, and Chennai, which handles cases from five states and accounts for around 30% of cases. She explains that many cases fail to progress because there are not enough benches to accommodate the volume of cases. She calls for more benches, better infrastructure, and trained personnel to improve the system’s capacity.

Ms. Merla also highlights a systemic issue she encountered during her time in the insolvency framework: around 95% of staff were outsourced. This led to instability in the workforce, as employees often left for other job opportunities, causing inconsistency in case management and negatively impacting the quality of work.

She went on to discuss the challenges related to the distribution of cases to creditors compared to previous systems, as well as procedural complexities. A significant concern was the absence of a comprehensive law for cross-border insolvency, which complicates matters when dealing with international cases. She calls for clearer provisions to address issues involving holding companies, subsidiaries, and service providers.

Another area of concern for her was the consolidation of cases, especially for complex projects like real estate. She emphasises the need for better coordination and information symmetry to reduce manipulation within the system. She also suggests that insolvency cases involving large or complicated companies should be consolidated for efficiency. Furthermore, she notes that the current framework tends to elevate operational creditors, which often leads to dissatisfaction among other stakeholders. She believes that this dissatisfaction undermines the overall effectiveness of the process. She proposes that proactive mediation, initiated before the Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP), could encourage better settlements and reduce the need for lengthy proceedings.

In conclusion, Ms. Merla calls for substantial improvements to the insolvency framework, particularly in areas such as procedural clarity, addressing cross-border issues, and ensuring adequate training and compensation for professionals. These steps, she argues, are essential for making the insolvency system more effective, efficient, and equitable for all parties involved.

Mr. Sumant Batra reflects on the significant transformation in India’s insolvency framework, noting that the initial work and foresight were groundbreaking at the time. He points out that the concept was futuristic and was something that countries like Singapore, Australia, and even India was starting to implement. However, back then, the confidence in the insolvency and possession laws was very low due to the previous experiences of users, which had shaken the system. He acknowledges that the system was in crisis, a crisis that had been concealed for a long time. For years, there had been mounting non-performing loans (‘NPLs’) and financial stress in banks, which were beginning to surface. This was a pivotal moment in India’s economic history.

During this time, Prime Minister Modi visited the USA in his first year after taking office. At a meeting with global institutions like the IMF and the World Bank, he promised to revitalize India’s economy and change how business was conducted in the country. The question posed to him during this visit was about insolvency law and what the exit strategy was for distressed assets. The Prime Minister responded by committing to have the law in place within a year, promising an investment climate that would make India a global leader.

Mr. Batra notes that, following this, the mandate was clear- India needed an insolvency law that could be implemented quickly to address the crisis. The final report on the new law came with a clear directive and a vision of India aspiring to be a global economy, seated at the center of the global financial table. The need for a comprehensive insolvency framework was urgent, especially considering cross-border insolvency challenges.

He mentions that the initial framework did not include provisions for cross-border insolvency, but due to time constraints, it was included as a compromise, providing cross-border protocols on an individual basis within the IBC. He also recalled the intense work that went into passing the IBC, highlighting the discussions and compromises that were made along the way. He reflects on the early days of implementation, describing how the infrastructure for insolvency resolution was built almost from scratch. At the time, there were only limited resources, and many aspects of the system had not yet been fully established. However, the government’s commitment, along with efforts from the team working on the law, eventually led to the creation of world-class infrastructure for insolvency resolution.

Mr. Batra praised the work done by the team responsible for building the system, acknowledging their hard work and dedication. He emphasises that much of the success of the IBC was due to the collective effort of this team, and he hopes that one day someone would document their contributions and the struggles they overcame. He also recognizes that many people who were initially unsung heroes in the process would later be celebrated for their role in shaping what the insolvency system looks like today.

He concludes by reflecting on the progress made, recognizing that although there was a long road ahead, the changes in mindset and approach had been significant. He notes that while statistics on success could be shared, the true impact of the law could only be fully appreciated by looking at the systemic transformation in how insolvency and distressed assets were handled in India.

Session 3: Litigation Funding: Maximising Value of Distressed Assets

This panel consisted of Dr. Sulette Lombard, Associate Professor of Law, UniSA Justice and Society, University of South Australia; Mr. Sanjeev Pandey, Part-time Advisor, Centre for Advanced Financial Research and Learning, Reserve Bank of India; Mr. Joe Durkin, Senior Vice President, Burford Capital, Dubai; Ms. Shweta Bharti, Managing Partner, Hammurabi & Solomon Partners, India; and Mr. S. Badri Narayanan, Chartered Accountant as the moderator.

Dr. Sulette Lombard discusses third-party funding (TPF) in litigation and proposed design options to strengthen the regulatory framework around it. She emphasises on the importance of considering TPF within its broader context, highlighting its growing relevance and potential in the global legal landscape.

Terms of Reference

- Comprehensive Report on Litigation Funding:Dr. Lombard outlines the need for a comprehensive report that explores the concept and framework of litigation funding. This would include a thorough analysis of the international market for third-party financing and the emerging global trends in litigation funding.

- Evaluation of the Legal Ecosystem in India:

The report would also assess the legal ecosystem for litigation funding in India, identifying its strengths and weaknesses. In particular, she focuses on evaluating the value of litigation funding in the context of India’s legal landscape.

The Challenges of Litigation Access

Dr. Lombard acknowledges that litigation has increasingly become a luxury only affordable to the wealthy. The cost of legal proceedings has made it difficult for ordinary individuals or businesses to pursue legitimate claims. However, the introduction of third-party funding, where litigants can receive financial support in exchange for a fixed percentage of the recovery, has provided a solution to this issue. This model has proven to be valuable, especially in jurisdictions with extraordinary civil litigation costs.

She further explains that third-party funding has allowed litigants to resolve their cases without the burden of upfront legal expenses, and it has helped facilitate access to justice for individuals or entities that would otherwise be unable to afford the costs of litigation. This shift has become particularly important in complex and high-value cases, where the financial burden on the litigant is often prohibitive.

Litigation Funding Landscape

Dr. Lombard also provided insights into the litigation funding landscape, particularly focusing on the scope and development of TPF in India.

Scope for Development of TPF in India:

- India as a Global Economic Giant

- Rising Commercial Legal Expenses

-

Limited Funding Alternatives:

Concerns About Legality and Regulation

Dr. Lombard also raises concerns about the legality and regulation of litigation funding, noting that while TPF is gaining traction globally, it is still a relatively new concept in many jurisdictions, including India. In India, there are concerns about the legality of TPF, especially with respect to whether it conflicts with the traditional understanding of champerty and maintenance, doctrines that have historically prohibited third parties from financing litigation.

She suggests that there is no need for proper regulatory framework to regulate litigation funding.

Recommendations

Dr. Lombard proposed several key recommendations to strengthen litigation funding in India:

- Develop Clear Guidelines

- Encourage Transparency and Ethical Practices

-

Promote Access to Justice

Practical and Ethical Concerns of Third-Party Funding (TPF)

Dr. Lombard further spoke about practical and Ethical Concerns of Third Party Funding

- Impact on the Legal System

- Proliferation of Litigation

- Size of the Funding Premium

- Funder Control Over Legal or Settlement Proceedings

- Nature of the Funding Agreement

-

Disclosure of Funding Agreement

Third-Party Funding in the Context of Insolvency

-

TPF Offers Obvious Benefits in Insolvency

-

Difference in Context Compared to Class Actions

She further concludes by recommending to ensure Regulatory framework (general) is conducive to development of TPF.

Mr Sanjeev Pandey discussed the challenges surrounding third-party funding and the nuances of rescue financing under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). He highlighted that although efforts have been made, certain issues persist that hinder the effectiveness of these mechanisms.

Rescue Financing under IBC

Interim Financing under IBC: Key Insights

- Special Financing Mechanism:

-

Post-Admittance Financing:

Importance of Interim Financing

- Critical Liquidity for Business Continuity

-

Enabling Rescue Financing

Key Constraints in Rescue Financing

- Regulatory and Legal Uncertainty:One of the major challenges in interim financing is the legal and regulatory uncertainty. The lack of case law, delays in adjudication by the National Company Law Tribunals (NCLTs), and the absence of clear legal precedents create risks for lenders when making financing decisions.

Additionally, there is uncertainty regarding the repayment period, the potential changes in asset classification due to delays, and the extent to which interest payments are covered under liquidation scenarios. These factors contribute to lender concerns, complicating the decision-making process.

- Banking System Challenges:The banking sector faces its own set of challenges that affect the success of rescue financing. One of the issues is the conservative lending practices that prevail, making it difficult for distressed firms to access necessary funds.

Furthermore, secured creditors often play a negative role in the process, sometimes impeding the progress of rescue financing. The lack of cooperation between creditors, particularly when their interests are misaligned, further exacerbates the difficulties in securing interim financing for distressed companies.

Ms. Shweta Bharti discussed the historical context and current challenges of third-party funding, emphasizing the need to understand the dynamics and the practical concerns associated with it.

Historical Context and Current Challenges

She notes that third-party funding, as a concept, can be traced back to the 19th century, referencing a judgment passed on this issue. However, despite the long-standing provision, third-party funding has not fully taken off in India. The provision itself has been around for a long time, but it hasn’t been widely embraced, and its effectiveness remains limited.

She highlights that there is still a lack of understanding and clarity surrounding the advantages of third-party funding, which is one of the reasons it hasn’t gained significant traction. She points out that, in today’s context, third-party funding can offer significant benefits, especially for professionals involved in high-stakes legal disputes. The ability to access funding would allow these professionals to contest matters in better panels, which would enhance their ability to represent clients effectively.

Key Considerations for Third-Party Funding

Ms. Bharti emphasized that there are multiple factors to consider when evaluating third-party funding:

- Asset and Liability Assessment

- Documentation and Readiness

-

Time and Agreement Framework

Do We Need Regulation for Third-Party Funding?

Ms. Bharti expressed her opinion that regulation of third-party funding may not be necessary at this stage. She believes that the market for third-party funding is still in its nascent stages in India, with only a few funders involved in small-ticket funding. Due to the limited activity in this area, introducing heavy regulation might not be required.

Session 4: Climate Change and Insolvency

This session consists of Dr. Eugenio Vaccari, Senior Lecturer in Law, Department of Law and Criminology, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK; Ms. Antonia Menezes, Senior Financial Sector Specialist, World Bank Group, USA; Mr. Sudhaker Shukla, Former Whole Time Member, Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India; Mr. Sumant Batra; and Mr. Pulkit Deora, Advocate, Supreme Court of India; Door Tenant, Enterprise Chambers, as the moderator.

Dr. Eugenio Vaccari addresses the intersection of climate change and insolvency, emphasizing how businesses are increasingly affected by climate-related risks, and how these risks impact the insolvency landscape. He provides valuable insights into the various types of risks businesses face due to climate change and how they can adapt and mitigate these risks.

Key Concepts in Climate Change and Business Risk

- Liability Risks — Mass Tort Liability Claims:Dr. Vaccari discusses the growing concern around liability risks, particularly related to mass tort liability claims. Companies are increasingly facing legal action due to their contribution to environmental degradation, with rising litigation claims in jurisdictions addressing climate-related harms.

- Physical Risks — Impact on Business Operations:He emphasizes on the physical risks of climate change, such as extreme weather events, rising sea levels, and shifting weather patterns, which directly affect how businesses operate. These physical risks can disrupt supply chains, damage infrastructure, and reduce productivity, especially in industries heavily reliant on natural resources.

- Reputational Risks — Contribution to Climate Degradation:Reputational risks are becoming more pronounced, as consumers, investors, and governments increasingly scrutinize businesses’ environmental impact. Companies that fail to address their contribution to climate change may face reputational damage, affecting their brand value, customer loyalty, and access to capital.

- Climate Adaptation — Adjusting to Climate Change:Dr. Vaccari discusses the importance of climate adaptation for businesses. Adapting to climate change involves making adjustments to operations, processes, and business models to ensure resilience in the face of changing environmental conditions. Companies must integrate sustainability practices into their long-term strategies.

- Climate Mitigation — Reducing Climate Risks:

Climate mitigation, the process of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, is also a key component of corporate responsibility. Dr. Vaccari highlights that businesses must take active steps to mitigate climate risks, such as adopting cleaner technologies, improving energy efficiency, and transitioning to renewable energy sources.

Insolvency and Climate Adaptation

Dr. Vaccari outlines the role of insolvency in managing climate-related risks and the importance of preparing businesses to cope with the impacts of climate change:

- Preparing for Shocks — Building Resilience:

- Coping with Shocks:

- Adapting to Climate Change:

- Managing Transition Risks During Insolvency:

-

Influencing Investment Decisions Before Insolvency:

Risks for Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs) and Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSEs)

Dr. Vaccari identifie specific risks faced by businesses in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) as well as micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSEs):

- Climate-Related Defaults Affecting Financial Systems:

-

Vulnerability of Corporations to Physical Risks in EMDEs:

Ms. Antonia Menezes spoke about the critical importance of addressing climate change, emphasizing its far-reaching effects on both lives and livelihoods. She starts by reflecting on the mission of the World Bank and the urgent need for action:

- World Bank Mission:She reminds the audience of the World Bank’s fundamental mission: to create a world free of poverty on a livable planet. This mission underscores the need to balance economic development with environmental sustainability, as climate change threatens not only the environment but also the future prospects of economies, particularly in vulnerable regions.

- Climate Change’s Impact on Lives and Livelihoods:

Ms. Menezes highlights how climate change affects people’s lives and livelihoods on a daily basis. It disrupts communities, especially in low-lying areas and regions vulnerable to extreme weather events, such as floods, droughts, and wildfires. These disruptions often result in the loss of homes, jobs, and agricultural productivity, leading to increased poverty and inequality.

She also shares her concerns about the global economic repercussions of climate change, pointing to significant data and projections.

Ms. Menezes presents estimates showing the potential impact of climate change on global GDP, underscoring how widespread environmental damage could reduce economic growth, particularly in emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs). She points out that failure to adapt to the changing climate would likely lead to slow transitions, which would exacerbate poverty and vulnerability in many regions. Without proper adaptation strategies, economies will struggle to recover from these shocks.

Role of Insolvency in Addressing the Climate Crisis

Ms. Menezes then shifted the focus to the role of insolvency law as a critical tool in managing the financial consequences of climate change. She emphasises that insolvency law could be leveraged not only as a means of addressing corporate financial distress but also as a part of the broader strategy for climate adaptation and mitigation.

- Insolvency Law as a Solution for Climate Adaptation and Mitigation:Antonia explained that robust insolvency law could provide the framework for companies to navigate financial stress arising from climate-related risks. These laws could help businesses restructure in a way that allows them to adapt to climate impacts while managing the financial challenges posed by these risks. Through well-structured insolvency proceedings, companies could also mitigate the financial fallout of environmental disasters.

- Dealing with Acute and Chronic Climate Shocks:

One of the key functions of insolvency law in the context of climate change, according to Antonia, is its ability to address both acute and chronic climate shocks. Acute shocks, like extreme weather events (e.g., floods, storms), can destroy assets and disrupt business operations. Chronic climate risks, such as rising sea levels or long-term droughts, can gradually undermine the financial stability of businesses. A robust insolvency law ecosystem would provide the necessary tools for companies and governments to manage these risks and develop effective responses, ensuring continuity and survival in the face of such disruptions.

Session 5: Emerging Scholars Group Sessions

Insolvency from the Lens of Emerging Scholars

This session consists of Dr. Eugenio Vaccari; Dr. Jonatan Schytzer, Senior Lecturer in Private Law, Faculty of Law; Uppsala University, Sweden; Dr. Sabrina Becue, Post-doctoral Researcher in Commercial Law, University of São Paulo Law School, Brazil; and Mr. Vasile Rotaru, DPhil in Law candidate, Faculty of Law, University of Oxford, United Kingdom.

Mr. Vasile Rotaru discusses the dynamics of financial distress, particularly focusing on issues like incomplete contracts, fragmented control, and the challenges posed by collection action problems. He explains that traditional methods of managing distress often involve bargaining under the shadow of litigation and the potential consequences of market practices.

Key Concepts in Financial Distress:

-

Financial Distress: Incomplete Contracts & Fragmented Control

Mr. Rotaru notes that financial distress is often characterized by incomplete contracts and fragmented control, which can lead to complications in resolving the situation. One of the major issues is the collection action problems, where multiple parties are involved, each with their own interests, making negotiations more complex.

-

Traditional Distress: Bargaining and Litigation

In traditional financial distress scenarios, companies and creditors typically engage in bargaining, often influenced by the looming threat of litigation. This is done with the awareness that the market may impose its own set of practices and consequences, which can complicate negotiations further.

-

Potential Distress: Anticipating Financial Challenges

Potential distress situations, Mr. Rotaru explains, are those that have not yet fully materialized but are likely to emerge. These are marked by uncertainty and a need for proactive strategies to manage and mitigate financial risks.

Role of Third-Party Intermediaries in Facilitating Negotiations:

Mr. Rotaru discusses how third-party intermediaries, such as brokers or mediators, can help facilitate multi-party negotiations in the context of financial distress. He point out that these intermediaries can be particularly useful in creating a cooperative environment where all parties have the incentive to reach a mutually beneficial resolution.

-

Transaction Cost Economizing:

- Bargaining Initiation

- Professional Process Organization

- Aligning Incentives:

-

Enhancing Fairness and Inclusiveness:

Mr. Rotaru emphasises that using intermediaries can lead to a fairer and more inclusive bargaining process. These professionals bring credibility and structure to the negotiations, which can be crucial in resolving disputes and ensuring that the interests of all stakeholders, including creditors and other parties, are taken into account.

-

Reputation and Relational Dynamics:

He also points out the importance of reputation in these processes. Intermediaries with a strong reputation for fairness can play a key role in reducing conflicts and ensuring that the negotiation remains focused on cooperation, not adversarial tactics. This is particularly important for repeat players such as creditors, who often deal with these situations regularly.

The ability of intermediaries to reduce strategic refusals and bring repeat-player creditors into negotiations can lower the expected costs of reaching a resolution, making the process more efficient overall.

Limitations and Trade-Offs:

Mr. Rotaru also addresses some of the potential limitations of using intermediaries in financial distress scenarios. While direct costs can be controlled through the use of reputable professionals, there are trade-offs to consider such as Market Competition, Cost Limitation, and Empirical Assessment.

Dr. Sabrina Becue discusses the significance and potential drawbacks of the Center of Main Interests (COMI) rule in the context of international insolvency proceedings, specifically in relation to the Multinational Cooperation and Bankruptcy Initiative (MLCBI).

Is COMI a Key and Necessary Rule?

Dr. Becue explains that the COMI rule has certain inherent disadvantages. While it serves as an essential part of the insolvency framework, its effectiveness and practicality in all situations must be reconsidered, especially with the increasing complexity of cross-border insolvencies.

The Role of COMI in the MLCBI

-

COMI as the Foundation for Identifying Main Proceedings

-

Defense of Modified Universalism

-

Predictability for Creditors and Consistency in Application

Session 6: Municipal Debt Restructuring

This session consists of Dr. M. S. Sahoo, Advocate; Former Distinguished Professor, NLUD; Former Chairperson, IBBI; Mr. Pramod Rao, Executive Director, Securities and Exchange Board of India; Dr. Eugenio Vaccari, Senior Lecturer in Law, Department of Law and Criminology, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK; and Prof. Laura N. Coordes, Professor of Law, Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, Arizona State University, USA [Virtually]. The moderator was Mr. Debanshu Mukherjee, Co-founder, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, India.

Mr. Pramod Rao discusses the need to diversify beyond traditional financing mechanisms, particularly through the development of the bond market. He highlights the importance of municipal bonds and shared some key statistics, noting that $75 million of outstanding coverage has been created over the past two years, with 60% of corporate lending now linked to these developments. This shift indicates a growing trend toward bond market utilization and diversification in financing strategies.

Tiny Market of Municipal Bonds:

Mr. Rao explains the basics of municipal bonds, which are debt instruments issued by third-tier government bodies as per the Constitution of India, with the power to levy taxes. Municipal bonds serve as an essential tool for local governments to raise funds for infrastructure and public services.

Key Points on Municipal Bonds:

- Basics of Municipal Bonds: These bonds are issued by local or municipal authorities to raise funds, typically for urban infrastructure projects.

- Issuances Outstanding: Mr. Rao mentions that approximately ₹2,700 crores worth of municipal bonds have been issued to date, signalling a modest yet growing market.

- Key Regulatory Concerns:Disclosure-Based Regime: He emphasises on the importance of a transparent disclosure framework for municipal bonds, ensuring investors have accurate and fair information.

- True and Fair Financials: Ensuring the financials reported by municipalities are true and accurate is vital for maintaining market confidence.

-

Adherence to SEBI Regulations: Municipal bond issuances must comply with the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) regulations, which govern capital markets and protect investor interests.

Challenges and Regulatory Framework:

Mr. Rao discusses the challenges municipalities face, such as the need for sound financial management and proper debt servicing. He highlights the importance of creating a DSRA to ensure timely repayment of debt obligations and prevent defaults. He also stresses the necessity for municipalities to balance their income and expenses to avoid financial distress.

Leverage and Default Concerns:

Mr. Rao acknowledges that leverage, while useful for financing, carries the risk of delay or default. He notes that municipalities with significant debt burdens could face challenges if cash flow projections fail to meet expectations, and this could lead to financial instability.

Proposal for a Municipal Debt Restructuring Forum:

To address these challenges, Mr. Rao proposes establishing a Municipal Debt Restructuring Forum under the aegis of SEBI regulations. This forum would be specifically for municipalities that have listed municipal bonds. The forum would serve as a structured platform for municipalities, banks, and bondholders to negotiate debt restructuring in case of financial distress.

Key Aspects of the Proposal:

- Applicability: The forum would apply only to municipalities with listed bonds, ensuring that it focuses on the most regulated and financially transparent entities.

- Participation: Participation in the forum would require agreement from banks and bondholders, ensuring that all relevant stakeholders are involved in the restructuring process.

- Rules of the Road:

- Secretariat: An entity would need to be designated as the secretariat for the forum. This body would oversee the forum’s functioning, ensuring fairness and transparency in the process.

-

Procedures: Clear procedures for initiating and managing debt restructuring discussions would need to be stipulated. This would ensure that all parties understand the process and the timeline for resolution.

Dr. M. S. Sahoo, Advocate, Former Distinguished Professor, NLUD, Former Chairperson, IBBI, speaks about how insolvency of each kind of entity had to be somewhat different from the other, including in the case of municipal insolvency, but the basic principles were the same as other entities. He also voices his agreement with the report to some extent. Dr. Sahoo underscores that we were in a market where resources were limited, which resulted in the resources competing with the users but gave investors the options to choose the profit according to their preferences.

While speaking on the aspect of risk in the insolvency regime, he states that overriding all the pre-insolvency rights of all stakeholders and every other law was the fundamental feature of insolvency globally. Higher the risk, lower is the rank of the stakeholder in terms of rights and interests, including the right to decide about the back-up plan.

Lastly, regarding the framework of municipal insolvency, he highlights that municipality could not be kept on a higher or lower level among the competing insurers.

Prof. Laura N. Coordes discusses the significant challenges faced by Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) in the United States, highlighting key issues affecting the sustainability and functionality of local governance in urban areas.

Key Challenges for Urban Local Bodies in the USA:

-

Aging Infrastructure

-

Revenue Losses

-

Housing Supply

-

Preemption / Intergovernmental Relations

-

External Threats.

How Services Are Funded in the USA:

Prof. Coordes also discusses the primary mechanisms by which services are funded in ULBs across the United States:

- Taxation: Local governments rely heavily on property taxes, sales taxes, and income taxes to fund public services. However, as mentioned, declining revenues from these taxes due to economic shifts have posed significant challenges in funding local government services.

- User Charges: Some services, such as water and waste management, are funded through user charges. This means that individuals who utilize these services pay directly for their consumption, providing a stable revenue source for specific municipal services.

- Inter-Governmental Aid: ULBs often receive aid from state or federal governments. These funds help bridge the gap between local tax revenues and the cost of essential public services. However, the availability of inter-governmental aid can vary depending on policy decisions at the state or federal level.

-

Debt Issuance/Municipal Bonds: Municipalities often issue bonds as a way to raise capital for large infrastructure projects or to meet short-term budgetary needs. These bonds are typically repaid over time through tax revenues or other local sources.

Comparing with USA, Dr. Eugenio Vaccari discusses the challenges faced by ULBs in the United Kingdom, highlighting several key issues that impact local governance and urban service provision.

Key Challenges for Urban Local Bodies in the United Kingdom:

- Increase in Population: The growing population in urban areas places additional strain on local services, infrastructure, and housing. As cities expand, there is a need to accommodate more residents, which can stretch available resources.

- Housing Services: Similar to other countries, the UK faces significant challenges in providing affordable and adequate housing. The demand for housing exceeds supply, making it difficult for local authorities to meet the needs of urban populations.

- Education, Health and Care (EHC) Plans and Special Educational Needs (SEN) Support: ULBs in the UK are under increasing pressure to provide support for children and adults with special educational needs, as well as to manage Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans. This places additional burdens on local budgets and resources.

- Adult Social Care: Providing adult social care services for an aging population is a major concern for local authorities. With an increasing number of elderly residents requiring care, the demand for services such as healthcare, housing, and support continues to grow.

- Lack of Investment in Preventative and Discretionary Services: Due to funding constraints, many ULBs have been forced to limit investment in preventative and discretionary services, which can help reduce the need for more intensive services later on. This results in increased long-term costs and greater pressure on public services.

- Inflationary and Market Pressures: Inflation and rising costs, particularly in the construction and public service sectors, are making it more difficult for local authorities to manage their budgets effectively. These market pressures are impacting the ability to deliver services and maintain infrastructure.

- Climate-Related Events: Climate change is increasingly affecting ULBs, particularly through more frequent and severe weather events. Local authorities must address the costs and risks associated with climate-related incidents, such as flooding, extreme heat, and storm damage.

-

Policy Decisions: National government policies can have a significant impact on local authorities. Decisions made at the national level may limit the resources available to ULBs or dictate how they can allocate funds, reducing their ability to address local needs effectively.

How Services Are Funded in the United Kingdom:

Dr. Vaccari also highlights the primary mechanisms through which services are funded in ULBs in the UK:

- Central Government Grants: Local authorities rely on grants from the central government to fund a significant portion of their services. However, these grants have been under pressure in recent years, leading to funding shortfalls for many ULBs.

- Council Tax Receipts: Council tax is one of the main sources of revenue for ULBs. However, the amount raised from council tax can be limited, especially in areas with lower property values, leading to disparities in funding between regions.

- Business Rates: ULBs also receive funding from business rates, which are taxes paid by businesses based on the value of their property. This funding is often essential for local authorities, but it can be volatile, depending on the economic performance of the local business community.

- Emergency Financial Support: In times of crisis or financial difficulty, ULBs may receive emergency financial support from the central government to cover urgent needs or unexpected costs.

- Capital Financing: Local authorities can borrow money or issue bonds to finance capital projects, such as infrastructure development, housing, and public services. These loans are typically repaid over time from future tax revenues.

-

Reserves: ULBs maintain financial reserves that can be used in times of financial distress or to cover unexpected expenses. These reserves are crucial for ensuring the financial stability of local governments but must be carefully managed to avoid depletion.

Professor Laura N. Coordes continues the discussion by exploring various approaches to restructuring Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) across different countries. She categorizes these approaches based on their comprehensiveness and level of government intervention.

Approaches to Restructuring ULBs:

- Comprehensive Special Insolvency Systems (e.g., USA):In countries like the United States, Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) often operate under special insolvency frameworks specifically designed for municipalities.

- Comprehensive Administrative Systems (e.g., Belgium, Italy, Japan, South Africa):Countries such as Belgium, Italy, Japan, and South Africa have implemented comprehensive administrative systems to handle ULB restructuring.

- Fragmented Special Administrative Systems (e.g., UK, Germany, Russian Federation):

In countries like the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Russian Federation, the approach to restructuring ULBs is more fragmented.

- Light-Touch Approaches (e.g., Bangladesh, Canada, Ghana, China, Uganda):

Some countries, such as Bangladesh, Canada, Ghana, China, and Uganda, have adopted light-touch approaches to ULB restructuring.

Professor Laura N. Coordes and Dr Eugenio Vaccari both compared the legal frameworks between USA and UK.

Session 7: Insolvency Scholars Forum Session

The Insolvency Scholars Forum (ISF) has been set up by ILA to bring together the community of academics in pursuit of education, research, and scholarship in the field of insolvency, and together, build a formidable cadre of insolvency scholars in the country. The members of ISF serve as a credible resource for ILA in its research initiatives and mentor the young researchers.

In this session the distinguished panel will discuss the papers called by ISF. The topics of the papers include-

A. Marrying Technology and Insolvency

B. Environmental and Social Governance and Insolvency

This session consists of Mr. Anoop Rawat, Partner, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co. India as the chair, and several eminent speakers, namely,

Ms. Anita Shah Akella, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Government of India; Mr. Debajyoti Ray Chaudhuri, Managing Director & CEO, National E-Governance Services Limited, India; Mr. Harry Lawless, Senior Associate, Norton Rose Fulbright, Australia [Virtually]; and Prof. Himanshu Joshi, Professor, FORE School of Management, New Delhi.

Prof. Himanshu Joshi speaks about the risks associated with insolvency and their connection to Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) factors, emphasizing the importance of understanding how ESG risks can impact a firm’s financial stability and long-term viability.

ESG and Insolvency Risks:

Prof. Joshi highlights that one of the primary risks of default arises when a firm’s future cash flows are insufficient to cover its debt service costs and principal repayment. This creates a significant financial strain and increases the risk of insolvency.

He further explained the two primary categories of ESG risks:

- Physical Risks — These include the direct impacts of climate change such as extreme weather events, natural disasters, or resource scarcity, which can disrupt a company’s operations and revenue streams.

-

Transition Risks — These relate to the changes a company must make to adapt to evolving environmental standards, regulations, and societal expectations. Failure to manage these risks can also have severe financial consequences.

ESG and Corporate Behaviour:

Using a practical example, Prof. Joshi illustrates that if an investor is unwilling to invest in companies that harm the environment, mistreat employees, or engage in poor governance practices, this represents a growing trend in finance that focuses on ethical investing. This movement, often known as ESG investing, is part of a broader attempt to make capitalism function more responsibly and to address the pressing threat posed by climate change.

The U-Shaped Curve of ESG Returns:

Prof. Joshi describes the ESG curve as U-shaped, suggesting that while the immediate returns from ESG practices may be low or even negative, in the long run, these practices tend to generate greater returns, both financially and reputationally. Thus, ESG is not just about immediate gains but rather about long-term sustainability.

Framing ESG Practices and Firm Value:

He also discusses how ESG practices influence firm performance and value, which can be broken down into several key factors:

- Cash Flow and Firm Performance: ESG practices can impact cash flow by creating efficiencies and improving operational resilience, which, in turn, enhances firm performance.

- Risk Management: ESG factors influence a company’s exposure to both systematic risk (market-wide risks) and idiosyncratic risk (company-specific risks). A well-managed ESG strategy can help reduce risks and thus positively impact a company’s capital structure and financing options.

-

Corporate Reputation: ESG practices play a significant role in shaping a company’s reputation. A strong reputation can drive customer loyalty, attract talent, and improve investor relations, all of which can enhance the long-term financial success of the firm.

Strong Creditors’ Rights in ESG-Driven Insolvency:

Prof. Joshi emphasises on the importance of creditors’ rights in the context of ESG-driven insolvency frameworks, discussing several key components:

- Automatic Stay on Assets;

- Secured Creditors’ Priority in Repayment;

- Management Stay During Reorganization; and

-

Restrictions on Restructuring.

Mr. Debajyoti Ray Chaudhuri speaks about the interplay of technology and insolvency, highlighting the role of the Information Utility (IU) in modern insolvency proceedings. He outlines the crucial functions and benefits of IUs in ensuring transparency, improving efficiency, and enhancing the overall process of debt resolution.

Role of Information Utility (IU):

- Electronic Repository: An IU serves as an electronic repository that stores and maintains critical financial information related to debts and defaults. It acts as a central platform where data on debtors, creditors, and associated financial transactions is securely recorded.

-

Authentication of Information: Information related to debt and defaults, submitted by creditors, is presented to debtors and guarantors for authentication. This ensures the accuracy and reliability of the data, which is crucial for fair proceedings in insolvency cases.

Alerts for Credit Monitoring:

Mr. Chaudhuri also discusses how the IU generates various alerts for monitoring and managing credit. These alerts help in timely interventions and decision-making:

- Alert 1: Default Alert — This alert notifies stakeholders when a debtor defaults on their obligations, allowing them to take appropriate action.

- Alert 2: CIRP Application Filing Alert — When a Corporate Insolvency Resolution Process (CIRP) application is filed, this alert notifies creditors and other relevant parties.

-

Alert 3: Public Announcement Alert — This alert signals the public announcement of the insolvency proceedings, ensuring that all interested parties are informed.

These alerts are sent to other banks, financial institutions, and creditors, keeping them updated about the debtor’s financial status and the progress of insolvency proceedings.

Debtor Behavior Under the IU:

Mr. Chaudhuri also touches upon the debtor behaviour tracked by the IU. The system records changes in the status of debtors, such as status change of records. A debtor’s financial status can change from Standard to Default, or from Default to Standard. This dynamic process is continuously updated in the IU, providing accurate real-time data to creditors and stakeholders involved in the insolvency proceedings.

Is There Life After Default?

He also raises an important question: Is there life after default? The transition from default to standard status is crucial, and it raises the issue of whether and how a debtor can recover from default, both financially and reputationally.

Time Period for Transition from Default to Standard:

Mr. Chaudhuri emphasises on the importance of understanding the time-period within which a debtor’s status can transition from Default to Standard. This transition is significant for both the debtor and creditors, as it affects the debtor’s ability to restructure and settle debts, and it influences creditors’ decisions regarding recovery.

He gives the following concluding pointers:

1. Default often emanates from the less regulated or non-regulated space.

2. Debtors are more focused on addressing the defaults to regulated entities;

3. Defaults also get cured in some cases.

4. Many debtors have defaults with only one creditor.

5. Creditors registered with the IU have access to tools for monitoring incipient stress of the connected debtors.

6. IU also provide digital tools to support CIRP applications.

Session 8: Insolvency Law in Emerging Markets and Developing Countries Perspective: Looking Backward Can Move Us Forward

Professor Aurelio Gurrea Martínez discusses the challenges faced by emerging markets and developing countries (EMDEs) in establishing a well-functioning insolvency system. He emphasises that three core pillars are necessary to create an effective insolvency system: a strong legal framework, a well-functioning institutional environment, and a supportive financial system.

Key Challenges in Insolvency Systems of EMDEs

- Institutional Environment: According to Professor Gurrea, many economies struggle with a weak institutional environment. He highlights the issue that insolvency courts in many countries are often understaffed and lack the resources and expertise necessary to effectively manage insolvency cases. Judges may not have the commercial or financial knowledge required to navigate complex insolvency proceedings.

- Restructuring Systems: Another critical issue is the lack of effective restructuring systems. In some countries, insolvency law may exist on paper, but the practical implementation of these laws is often impeded by weak institutional support. For example, Colombia has attempted to update its financial restructuring mechanisms, inspired by the US Bankruptcy Code’s Section 364. However, the country’s lack of restructuring capacity has hindered the adoption of these mechanisms in practice.

- Legal Framework: Even when there is a law in place, it may not be attractive or effective for both debtors and creditors. For example, in many emerging economies, insolvency laws may replace a company’s management with an external administrator, which is often unappealing to debtors. This lack of balance between debtor and creditor interests further weakens the insolvency system.

-

Priority and Creditor Rights: Professor Gurrea also discusses how the insolvency laws in some countries often fail to provide proper priority structures for creditors, leading to ineffective debt restructuring. For instance, some laws may allow shareholders to receive value in certain circumstances, even if creditors would be better off in a different scenario. This issue arises particularly in countries that relax the absolute priority rule, creating conflicts between debtors and creditors and hampering fair restructuring outcomes.

Empowering Creditors

Professor Gurrea argues that empowering creditors in insolvency proceedings could be beneficial in many EMDEs, particularly when the judiciary lacks commercial expertise. In such cases, creditors could be entrusted with more control over decision-making, ensuring that the restructuring process is driven by those with the most knowledge of the financial landscape. By shifting decision-making power to creditors, it might be possible to address inefficiencies and provide more effective restructuring.

DAY THREE [16th March 2025]

Session 9: Mediation in Insolvency:

Justice A.K. Sikri emphasizes on the value of mediation as one of the best methods for making justice more accessible. He underscores the importance of mediation as an alternative dispute resolution mechanism, especially given the growing burden on Indian courts. Drawing from the success observed in the United States, the introduction of mediation in India aims to ease the strain on the judicial system and offer a more efficient means of resolving disputes.

In the context of insolvency, Justice Sikri highlights the critical role of time management. The insolvency process is time-sensitive, with strict timelines set for various steps to ensure that the entire process is completed within a prescribed time frame. Time, he notes, is the most crucial factor in insolvency proceedings.

He also points out the responsibility of company directors when the company is facing financial distress or insolvency. Directors must act with due diligence, especially during the “twilight zone” period when the company’s future remains uncertain.

Lastly, Justice Sikri advocates for mediation over adversarial systems in scenarios where time is of the essence. In such cases, mediation can serve as a more efficient and effective alternative to the traditional adversarial process, helping parties reach a resolution in a timely manner while minimizing the prolonged disputes that often arise in court battles.

Justice Christopher S. Sonchi addresses the question of whether mediation is more about finding a solution or about delivering justice. He notes that mediation, unlike other legal processes, is not universally standardized at the international level. In the United States, mediation is typically governed by standing orders and local rules, making it a more localized practice.

Justice Sonchi reflects on his own experience as a sitting judge who also mediated cases. He recalls how, during mediation sessions, the parties often valued his opinion on the merits of their case. This, he suggests, is a key difference in the mediation process—a more personal and engaged approach. The communication between the parties, or even the three parties involved, is essential in resolving conflicts.

He observed that there is a lot of anger from the parties, along with a tendency to focus on their legal arguments. When it was his turn to communicate with the other side, he aimed to deliver a more concrete, practical approach to the matter. Justice Sonchi believes this kind of focused communication is a significant reason why mediation works, even in commercial cases. He highlights that, in such cases, there is often frustration and dissatisfaction over small differences in settlements—whether a party receives 30 or 35 cents on the dollar, for example. The emotions involved can be intense.

However, he emphasises that the success of mediation is not solely determined by whether a resolution is reached. Even if a mediation attempt fails, it still serves a valuable purpose by setting the process in motion and fostering dialogue between the parties. This alone can often pave the way for future resolutions, making the mediation process itself successful in a broader sense.

Mr. James H.M. Sprayregen discusses the various approaches to mediation, emphasizing the importance of considering different types of disputes and the unique dynamics at play. He notes that in certain situations, such as disputes between countries, the goal is often to avoid the costly and time-consuming process of litigation. Mediation offers a way to resolve conflicts more efficiently and with greater clarity for the parties involved, ultimately leading to a more satisfactory resolution.

Mr. Sprayregen further highlights the complexity of the mediator’s role, especially when the mediator is also acting in a judicial capacity. He points out the interesting dynamic between the mediator and judge, as they are bound by distinct roles but must often navigate these boundaries carefully. This relationship is not the same in every case, but in many instances, it plays a critical role in the success or failure of the mediation process. The tension that arises from these roles can sometimes add an extra layer of challenge to the process, particularly when parties are reluctant to reach a resolution.

He acknowledges that while mediation can be a highly effective mechanism, there are instances where it fails to reach a resolution. Nonetheless, he believes that even when a mediation process doesn’t succeed, it still provides value by helping parties understand each other’s positions better and moving the process forward.

Mr. Sprayregen also touches on the fact that, in some cases, mediation is used alongside ongoing legal proceedings, which adds an interesting dynamic. The interaction between the mediator and the judge in such scenarios creates an environment where both are attempting to facilitate a resolution, but their roles remain distinct.

Lastly, he comments on the variation in mediation approaches, noting that in some instances, multiple mediators or different strategies may be employed to address specific cases. However, he recognizes that there is still much to be learned about how these mediation processes work in practice, especially compared to more established systems in places like the United States. He believes there is potential for growth and improvement in the way mediation is understood and implemented, especially in cases involving complex commercial or international disputes.

Professor Anthony J. Casey further elaborates on the challenges of mediation, particularly in complex insolvency cases involving numerous parties. He explains that when there are many parties—ranging from ten to potentially thousands—the traditional alternative to mediation is direct negotiation. This approach can quickly become overwhelming, especially if each party is engaged in bilateral negotiations. When multiple parties are negotiating separately, the process can devolve into a series of conflicting interests and strategies, making it difficult to find a resolution. For example, one party might fear that if another party moves in a certain direction, it could result in a disadvantage for them.

This is where mediation proves valuable, as it provides a neutral space for communication. Parties may not feel comfortable expressing certain concerns directly in bilateral negotiations, but a mediator can step in to facilitate that conversation. The mediator acts as a bridge, connecting the dots between different parties and helping them to understand each other’s perspectives. This can lead to solutions that parties might not have been willing to consider on their own.

Professor Casey emphasizes that mediation can still be effective even in cases involving large numbers of entities, where confrontations are almost inevitable. While these challenges may seem daunting, mediation remains worthwhile because it helps move the process forward, even in the most complex cases. In traditional bilateral negotiations, without mediation, some valuable issues might never even be raised, making the mediation process invaluable.

From an academic perspective, Professor Casey discusses the use of mediator proposals—when a mediator suggests a possible solution to help parties reach an agreement. This happens when the parties are close to a deal but haven’t quite reached consensus. For instance, if two parties are negotiating over a $2.2 million settlement, the mediator might propose a specific figure or offer to help break the deadlock. The value of such proposals lies in the mediator’s ability to suggest an offer that both sides might find reasonable. However, Professor Casey acknowledges the risks associated with mediator proposals. If a mediator proposes an offer, some parties might feel pressured to accept, particularly if they have been told that this is their best option.