What happens when an insolvency process takes too long? What does it mean for creditors, employees, and stakeholders waiting for resolutions that never come about? In one of India’s most intricate corporate insolvency matters, the liquidation of an aviation company and a corresponding judgment of the Supreme Court of India cast a spotlight on these critical issues.

A premium airline had been in immense financial distress, leading to its corporate insolvency resolution process (CIRP) in 2019. Despite an approved resolution plan offering a glimmer of hope, its failure to materialise has culminated in liquidation, with stakeholders grappling with substantial financial losses. The question is: How did a well-regarded plan go so wildly wrong?

At the heart of the recent decision of the Supreme Court to order liquidation of SBI v. Murari Lal Jalan & Florian Fritsch Consortium (Jet Airways)1, lies the promise of timely resolution — a core objective of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC). The Supreme Court rejected the Consortium’s plea, which was the successful resolution applicant (SRA), for an extension of time to implement the resolution plan because it had continually failed to comply with the terms of the resolution plan, including compliance with payment obligations such as payment of INR 4783 crores to creditors in multiple tranches. By refusing leniency, the Court held that deviations from the agreed plan undermines the IBC’s intent to facilitate efficient corporate debt resolutions.

The Supreme Court also observed certain systemic challenges inherent in the insolvency process. The National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) and the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT) were established, inter alia, to streamline resolutions and adjudicate competing claims efficiently. However, from an operational perspective, various procedural complexities have contributed to delays or deviations from statutorily prescribed timelines. In Jet Airways2, the NCLAT permitted the adjustment of an INR 150 crores performance bank guarantee (PBG) against the INR 350 crores fund infusion requirement, a decision that underscored significant procedural ambiguities. Such issues and interjections have not only contributed to delays in resolution timelines but have also raised critical concerns regarding stakeholder confidence in the robustness and efficiency of India’s insolvency framework.

In 2020, there was hope that the airlines could be brought back to life when its resolution plan was approved, but stakeholders had to sell all assets as quickly as possible. Nevertheless, the deadline was not met despite numerous extensions for compliance — a factor emerging from the financial sensitivity of the case rather than a derivative statutory power. The Supreme Court observed that the Tribunal faces infrastructural and operational limitations, with members often presiding over multiple Benches or serving on a part-time basis. These limitations have not only impeded the timely resolution of this insolvency matter but have also highlighted systemic delays pervasive across various facets of the insolvency framework.

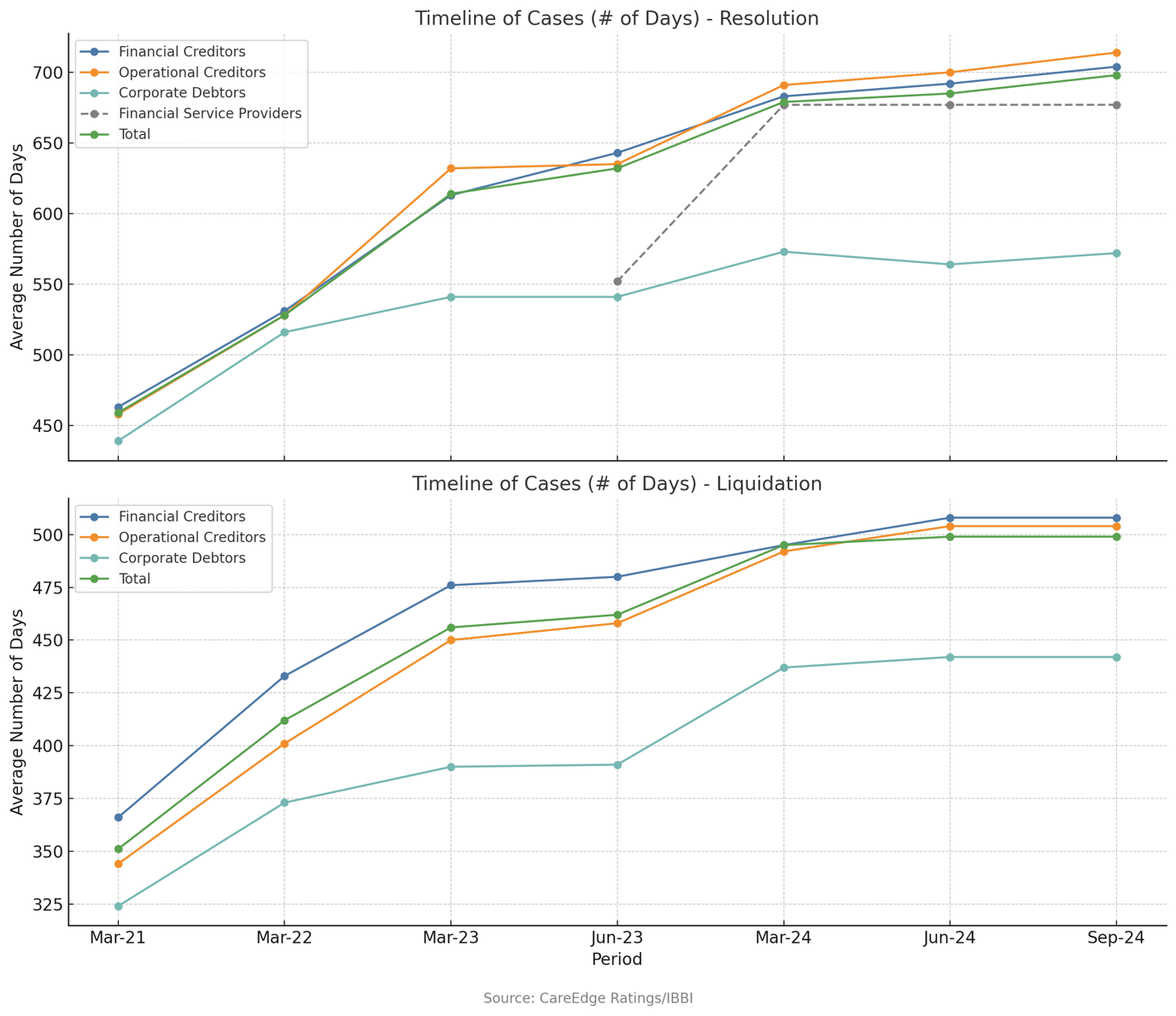

According to reports,3 several CIRPs extend far beyond the mandated 180 days (extendable up to 330 days) with many cases taking more than 600 days to resolve. Noting that prolonged delays merely facilitate uncertainty and also dilute the objective of resolution under the IBC, the Court said that the IBC was aimed at ensuring timely arrangements for bankruptcy and “speedy restoration” of the corporate debtor to its effective management.

As a corollary to the Supreme Court’s observations and the data highlighting protracted insolvency timelines, it is evident that tribunals face inherent constraints that inadvertently contribute to procedural delays in insolvency proceedings. While the IBC was designed to streamline the resolution process, challenges such as shortfalls in the number of members of the Bench, limited infrastructure, and occasional lapses in adhering to the prescribed timeline have affected its implementation. Further, it would not be out of place to mention the frequency of adjournments being sought by counsels.

On occasion, due to the technical nature of certain matters, members do not always possess the specialisation or expertise which may be crucial to the adjudication of such disputes. Pertinently, disputes under the IBC and company law disputes jurisdictionally fall before NCLT/NCLAT, each having their own procedural and substantive aspects emerging from their respective rules and legislations. A practitioner’s perspective, or even frequenting either forum, would reveal significant time being dedicated to IBC-related disputes, consequently causing company law related issues to be taken up on belated dates.

A related systemic procedural challenge emerges from the frequent rotation and temporary appointments of adjudicating members. This lack of Bench permanency creates difficulties during final hearings, where the presiding members may be unfamiliar with the case’s procedural history and factual matrix. Counsels are frequently compelled to revisit previously argued positions and re-establish case backgrounds for newly constituted Benches, leading to procedural redundancies and delays. Not only does this undermine the cornerstone principle of expeditious resolution under the IBC but also compromises the quality of justice delivery. The time-sensitive nature of insolvency proceedings, which are designed to facilitate swift resolution of corporate distress, is particularly frustrated when final arguments must be repeatedly reconstructed for different Benches. This rotating door of adjudicating members thus poses a substantial impediment to the efficient administration of India’s insolvency regime.

Furthermore, it is pertinent to mention that resolution applicants also play a significant role in causing delays before NCLT/NCLAT. More often than not, there are various requests regarding amending/modifying the resolution plan or time being sought for the completion of the same. When tribunals are compelled to routinely accommodate multiple requests from resolution applicants to amend or extend their plans, it creates a problematic cycle of iterative modifications. For instance, the applicant in Jet Airways case4 was seeking an extension and alteration of the terms of the PBG which was not in line with the resolution plan.

Effectively, there appears to be issues related to enforcement of the resolution plan, which is the primary focus of the jurisdictions of NLCT/NCLAT. It is settled law that the commercial wisdom of the Committee of Creditors (CoC) is sacrosanct, and continuous requests for amendment of the resolution plan strike at the core of such a position. Further, in the absence of the NCLT/NCLAT’s approval of the resolution plan, it remains devoid of its binding value as under the scheme of Section 31 of the IBC.5 It is also interesting that in the absence of approval of the resolution plan, consequences emerging from Section 74 of the IBC are not triggered in the event of contravention of the terms of the resolution plan.

However,in Jet Airways6, the NCLT and NCLAT were pleased to grant extension requests instead of enforcing the terms of the resolution plan as had been settled. This is problematic at two levels. Firstly, this concerning trend potentially undermines the sanctity of approved resolution plans. Such leniency rather encourages resolution applicants to view their commitments as flexible arrangements rather binding obligations. Secondly, the conduct of resolution applicants demonstrates priority towards seeking reconsideration of resolution plans rather than aiding the Tribunal on the enforcement of the same. This endemic tardiness in resolution processes represents more than just calendar overruns; it signifies a fundamental challenge to the IBC’s core objective of swift and efficient resolution of corporate insolvency.

Consequently, creditors and other interested parties often face prolonged periods of uncertainties. For example, in the instant case, the long delay processes resulted in the airline going for liquidation and creditors, including reputed banks, had to bear the risk of losing all their dues. And the length of the process dilutes the value of the assets and affects employees and others who are then compelled to wait for their outstanding amounts.

A significant takeaway from Jet Airways case7 is the pressing need for stricter compliance. The Supreme Court’s decision8 to wind down the airline turned out to be a timely reminder that tolerance for deviation from plans drawn for resolution must be low under the IBC, specifically one under Section 33(3). The Supreme Court in its judgment9, also suggested a revamp of the entire insolvency ecosystem, including expanding the capacity of tribunals, special training of Judges in commercial and insolvency law and dedicated insolvency courts. Further, the Court also highlighted the need for transparency and accountability and greater disclosure of bidders and settlement terms in cases involving public-interest entities. Such transparency could reduce information asymmetry and foster trust amongst stakeholders. In furtherance of the same, the Court also suggested that the Committee of Creditors (CoC) must document its reasons for approving or rejecting resolution plans.

Despite these efforts, significant gaps persist. The Court has recommended structural changes, such as forming Oversight Committees to monitor CoC functioning and implementing independent mechanisms for enforcing standards. To that effect, the Court further proposed mandating Monitoring Committees’ post-resolution to ensure smooth handovers and timely execution of plans.

Recovery rates and financial performance

According to a report published by CareEdge Ratings, the corporate insolvency recovery rate as of Q2FY25 is at 31.04% compared to 43% in Q1FY20. In most of these cases, creditors are still receiving massive haircuts, typically 70% of the admitted claims. The resolution to liquidation ratio still improved marginally from 0.88 in Q1FY25, coming in at 0.68 in Q2FY25, compared to 0.21 in FY18.

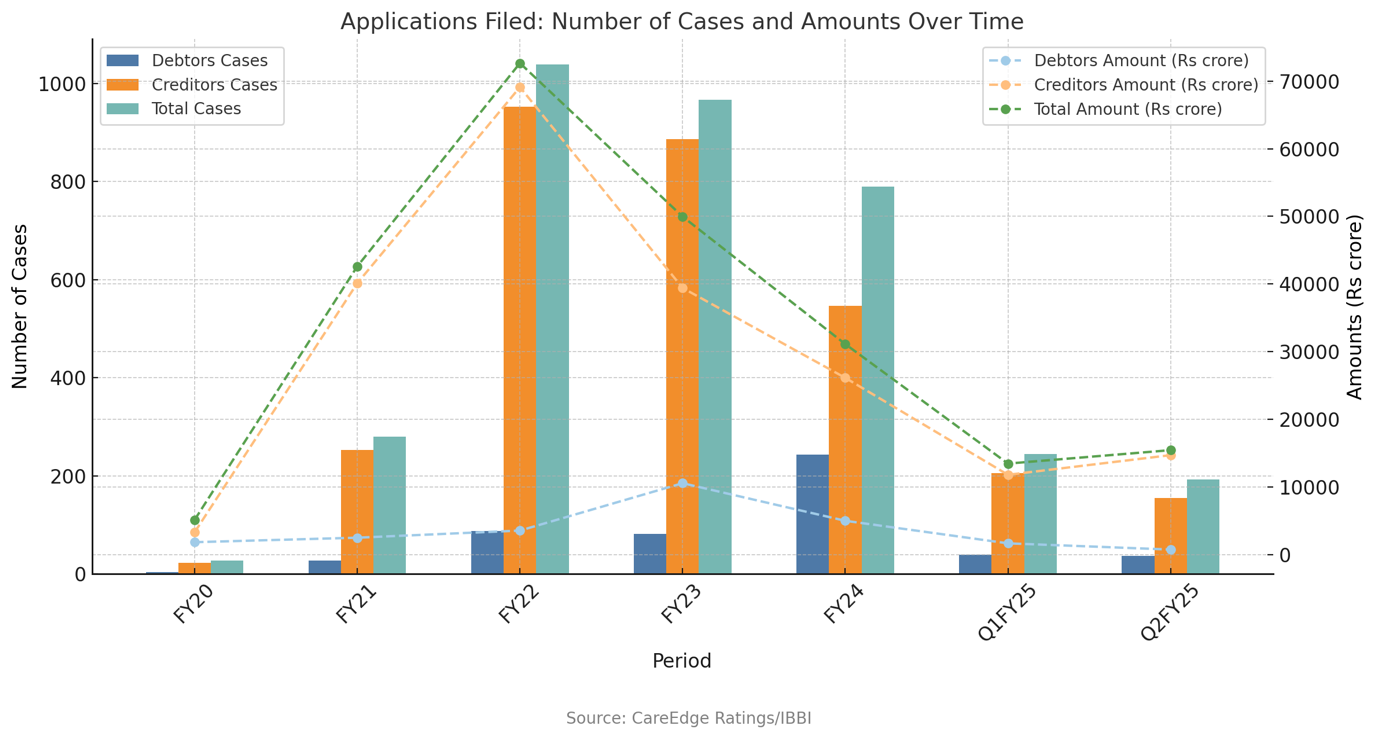

While the pace of escalation is decelerating, the number of new insolvency cases remains at a constant surge, although certain improvements are reported. On the contrary, the case inflow into the insolvency process had risen by nearly 13% year-over-year (YoY) by Q2FY25. However, the inflow of cases is lesser than in earlier times, like FY20.

The report stated that average timelines for different types of CIRP cases and liquidation are rising progressively across the board. This is evident from the fact that in September 2024, financial creditors waited for an average of 704 days to get their issues resolved and operational creditors waited 714 days. Due to such deviation from statutory timelines, for instance, a few of the applications have now gone into liquidation. Over 55% of cases are still pending after a two-year period, and a further one-in-five is delayed up to one to two years.

As far as cases under CIRP and their outcomes are concerned, the data reveals an ambivalent picture. Out of the 8002 cases admitted till September 2024, only 13.3% cases witnessed a resolution plan approval. The majority (nearly one-third) were liquidated. More than 15% of the cases were closed at the appeal, review or settlement stage, while 14% were withdrawn at the application stage (withdrawal of application for initiation of CIRP under Section 12-A of the IBC).

Lessons on timelines and accountability from Jet Airways

The broader question remains whether the IBC is sufficiently equipped to handle sector-specific challenges. As suggested by the Supreme Court in Jet Airways10, the introduction of a Monitoring Committee and enforceable codes of conduct for the CoC could streamline the resolution process. Despite the position that the commercial wisdom of the CoC is sacrosanct and its decisions cannot be overruled by the tribunals, this principle is not consistently upheld in practice. Several hearings diverge from the enforcement of resolution plans towards the flurry of requests for amendment/modification the same, adjournment requests from counsels and various practical issues.

Therefore, the Jet Airways11 insolvency, at both a procedural and substantive level, had certain valuable takeaways: (i) tribunals should adhere to timelines and avoid interventions that could hamper CoC approved plans; (ii) vacancies in NCLTs and NCLATs should be filled with domain experts; (iii) CoCs must exhibit fairness and accountability in approving or rejecting resolution plans; (iv) successful resolution applicants must honour obligations without treating them as conditional; (v) tribunals must limit discretion in altering resolution plan terms or timelines; (vi) infrastructure and operational deficiencies in tribunals must be addressed; (vii) a statutory provision for Monitoring Committees should be introduced to streamline corporate debtor handovers (as suggested by the Supreme Court); and (viii) the Government should explore independent oversight mechanisms for better enforcement of CoC Guidelines.

Reflections of practice

A practitioner’s perspective would reveal that various aspects of insolvency proceedings require consideration for reform. For instance, the misuse of the IBC as a debt recovery mechanism fundamentally contradicts its legislative intent. Creditors frequently leverage the IBC threat to coerce settlements, particularly concerning operational creditors, prompting legislative consideration of pre-institution mediation requirements. It is crucial to recognise that the NCLT and NCLAT were never designed as recovery forums. To preserve the integrity of the insolvency process, a preliminary screening mechanism deserves consideration of being instituted to filter legitimate insolvency claims from those filed maliciously or merely to recover debts. Such reform would not only alleviate tribunal burden but also restore the IBC to its intended purpose — facilitating corporate rescue and value maximisation rather than serving as a collection instrument.

Further, the insolvency regime also invites consideration of critical threshold reforms to enhance efficiency and reduce tribunal congestion. Primarily, the CIRP threshold for financial creditors (currently standing at Rs 1 crore) demands reconsideration and upward revision to filter out minor claims that disproportionately burden the system. Equally important is the establishment of a monetary threshold for appeals from NCLT to NCLAT, similar to the appellate structure for tax related disputes, which effectively restricts appeals below certain pecuniary values (minimum threshold for appeals being Rs 60 lakhs for Income Tax Appellate Tribunal (ITAT), Rs 2 crores for High Courts and Rs 5 crores for the Supreme Court of India). This would substantially improve the NCLAT’s efficiency by doing away with appeals of low value, while focusing resources on matters of significant financial impact.

Furthermore, minimising avenues for interference with approved resolution plans is essential to maintain certainty and finality in the insolvency process. For instance, High Courts should exercise judicial restraint in reconsidering approved resolution plans or interfering with the CIRP process (impacting the IBC timelines), especially, while specialised forums such as NCLT and NCLAT have been designed to facilitate the same. Fortunately, the recent induction of 24 new members into NCLTs across the India has increased Bench strength, collectively aiming to accelerate case disposal rates and aiding the preservation of the time-bound nature of insolvency proceedings.

*Partner, Khaitan & Co.

**Principal Associate, Khaitan & Co.

***Senior Associate, Khaitan & Co.

****Associate, Khaitan & Co.

3. “Insolvency Process Getting Only Longer and More Tedious; Average Resolution Time Rises to 761 Days in April-Sept”, (Financial Express, 12-11-2024) available at <https://www.financialexpress.com/business/industry-insolvency-process-getting-only-longer-and-more-tedious-average-resolution-time-rises-to-761-days-in-april-sept-3662670/>.

5. Ebix Singapore (P) Ltd. v. Educomp Solutions Ltd. (CoC), (2022) 2 SCC 401.