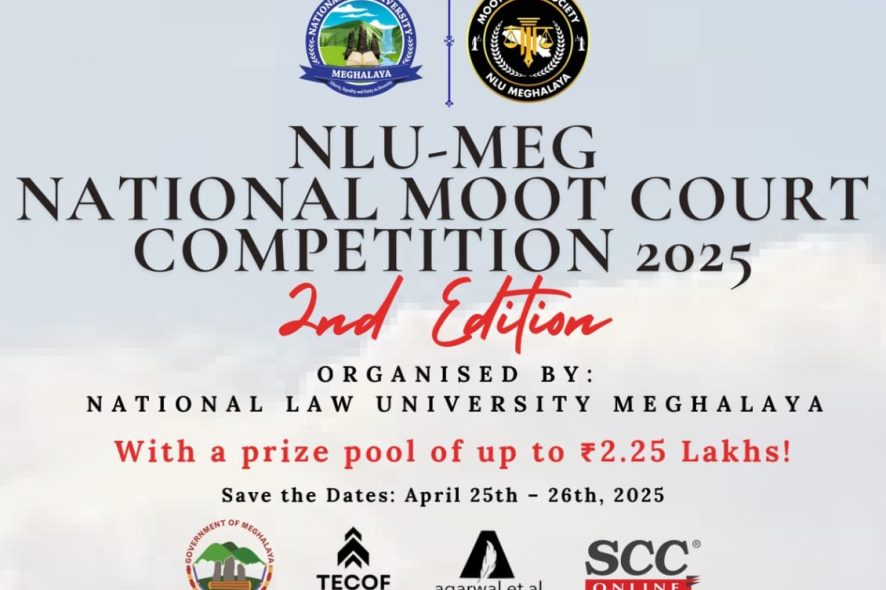

2nd NLU Meghalaya National Moot Court Competition, 2025.

Welcome to the Abode of Clouds – Shillong!

The National Law University, Meghalaya (NLU Meg), nestled in the picturesque hills of the ‘Scotland of the East’, proudly hosts the 2nd edition of the NLU Meghalaya National Moot Court Competition, 2025. Organized by the Moot Court Society (MCS) in association with the University’s academic leadership, the competition reflects our unwavering commitment to fostering advocacy, scholarship, and legal excellence.

As the first National Law University in Meghalaya, NLU Meg was established with a vision to drive legal educational reforms and contribute to the transformation of India’s legal system through evidence-based research and policy innovation. The University prioritizes learning outcomes over information overload, preparing students with the practical and intellectual tools needed to meet the demands of an evolving legal landscape.

This year’s moot court competition centers on a contemporary and pressing legal issue—the intersection of Consumer Protection Law and Advertising Ethics—inviting participants to navigate complex dimensions of statutory interpretation, judicial precedents, and regulatory frameworks. The proposition challenges students to think beyond legal theory and explore practical solutions grounded in justice and equity.

Under the guidance of the Moot Court Society (MCS)—a key pillar of legal training at NLU Meg—students engage in rigorous simulations of court proceedings. The Society is credited with organizing the highly successful 1st NLU Meg–NHRC National Moot Court Competition in 2024. Building on that success, MCS has expanded into dedicated National and International Committees, with plans underway to host the first International Moot Court Competition in North-East India.

Echoing the vision of excellence, Prof. Indrajit Dube, Vice-Chancellor of NLU Meghalaya, shares in his message:

“This event is more than just a competition; it is a platform for shaping the future of legal advocacy. Mooting brings statutes and judgments to life. Advocate fervently but also value diverse perspectives. Let this moot be a celebration of justice and a testament to your potential as vanguards of the legal fraternity.”

We are honored to welcome 20 participating teams from across the country to this arena of intellectual rigor and spirited advocacy. The event not only promises to test legal acumen and research abilities but also celebrates the transformative power of law in a democratic society.

25th April 2025 (Day 1): Registration | 8:30 AM

The second edition of the NLU Meghalaya National Moot Court Competition officially kicked off on Friday, 25th April 2025, with the registration process beginning at 8:30 AM. The Moot Court Society welcomed all 20 participating teams at the reception desk, where they completed their registration smoothly with the assistance of dedicated student volunteers.

The teams were then directed to the designated breakfast area, where they had the opportunity to interact with fellow participants, organizers, and volunteers—setting the tone for a day filled with competitive spirit and camaraderie.

Registration Desk

|10:30 Am |Inauguration Ceremony |

The day began with the Inaugural Ceremony at 9:30 AM, marking the formal commencement of the 2nd NLU Meghalaya National Moot Court Competition, 2025. Dignitaries, faculty members, judges, and participating teams gathered at the ceremonial venue, bringing anticipation and excitement to the proceedings.

The Inaugural Ceremony commenced at 9:30 AM with great pomp and grace in the serene and mist-kissed surroundings of Shillong, the ‘Scotland of the East’. The event was graced by esteemed dignitaries, including our Chief Guests:

- Hon’ble Mr. Justice I.P. Mukerji, Chief Justice of the High Court of Meghalaya and Chancellor of NLU Meghalaya

- Hon’ble Mr. Justice W. Diengdoh, Judge, High Court of Meghalaya

- Hon’ble Mr. Justice H.S. Thangkhiew, Judge, High Court of Meghalaya

To honor their presence, the event began with a mesmerizing Kathak dance performance, paying tribute to India’s cultural richness and offering a graceful welcome rooted in tradition. The vibrant movements of the dance resonated with the spirit of celebration and reverence that Shillong so naturally embodies.

The Chief Guests were then ceremoniously welcomed by the Vice Chancellor, Prof. (Dr.) Indrajit Dube, along with the organizing committee, through the watering of plants—a symbolic gesture of nurturing growth, knowledge, and sustainability amidst the lush, green highlands of Meghalaya. This moment not only reflected the university’s eco-conscious ethos but also Shillong’s deep connection to nature and harmony.

Prof. (Dr.) Indrajit Dube also felicitated all the honored guests, acknowledging their presence and invaluable contributions to the legal community. Their guidance and encouragement continue to inspire the vision and mission of NLU Meghalaya.

In a solemn tribute, the gathering observed a one-minute silence in memory of the victims of the recent Pahalgam terrorist attack, reflecting our collective grief and standing in solidarity with those affected.

This was followed by the Welcoming Address by Prof. (Dr.) Indrajit Dube, Vice Chancellor of NLU Meghalaya. He addressed the participants and dignitaries with warmth and purpose. In his speech, he underlined the importance of moot court competitions as transformative tools in legal education—platforms where statutes meet storytelling, arguments refine intellect, and the courtroom becomes a classroom. He highlighted how the initiative was envisioned not merely as a competition, but as a forum to cultivate advocacy, legal reasoning, and ethical responsibility among budding legal professionals.

Prof. Dube extended heartfelt gratitude to the Hon’ble Chief Minister of Meghalaya for his support and generous funding of the competition, a gesture that underscores the state government’s commitment to promoting legal education and excellence in the region.

Prof. Dube also extended a heartfelt welcome to all the students, faculty members, legal luminaries, and guests present, setting an inspiring tone for the events to follow.

Following the Vice Chancellor’s warm welcome and address, the dignitaries took to the stage to share their thoughts and wisdom with the gathering.

Hon’ble Mr. Justice H.S. Thangkhiew delivered an encouraging and heartfelt address, reminding the audience that every effort made by the participants—each memorial drafted, each argument prepared—deserves recognition and appreciation. His words resonated deeply with the young legal aspirants, as he emphasized that the true essence of mooting lies not merely in competition, but in the pursuit of knowledge, discipline, and skill-building. With clarity and compassion, Justice Thangkhiew urged students to carry forward the spirit of learning and to cherish this experience as an integral part of their journey into the legal profession.

The gathering then had the honor of hearing from Hon’ble Mr. Justice I.P. Mukerji, Chief Justice of the High Court of Meghalaya and Chancellor of NLU Meghalaya. His address was both insightful and stirring, drawing from history, policy, and contemporary relevance.

Justice Mukerji reflected on how India’s legal system has always drawn the best minds of the country—from Mahatma Gandhi to Dr. B.R. Ambedkar—and how the legal fraternity has consistently stood at the forefront of national transformation. He spoke passionately about the critical responsibility of senior members of the judiciary and legal educators to guide, nurture, and mould the next generation of lawyers, especially as the field continues to attract bright, socially conscious individuals.

In a profound observation, he highlighted how the country must be run with both general laws applicable nationwide and special laws crafted for regional and cultural specificity. Justice Mukerji shed light on the unique legal framework of the Northeast, including the use of customary laws, tribal regulations, and special constitutional provisions, which make the region a vibrant and complex legal landscape. He emphasized that understanding these nuances is vital for any legal professional aiming to contribute meaningfully to the development and protection of diverse communities.

Touching upon the importance of moot courts, he acknowledged their role in shaping articulate, analytical, and responsible lawyers. Justice Mukerji encouraged students to view mooting not just as academic practice but as a rehearsal for the real courtroom—where law, life, and justice intersect.

He encouraged participants to develop their language and courtroom communication skills, to read landmark judgments, and to approach mooting not just as a competition, but as a training ground for real-world advocacy.

His speech resonated as a powerful call to the future lawyers of India: to engage deeply, think critically, and uphold the highest ideals of justice.

The inaugural ceremony gracefully ended with the Vote of Thanks delivered by Professor Umeshwari Dhakar, Faculty Coordinator of the Moot Court Society, NLU Meghalaya.

In her address, she expressed deep gratitude to the Hon’ble Mr. Justice I.P. Mukerji, Hon’ble Mr. Justice H.S. Thangkhiew, and Hon’ble Mr. Justice W. Diengdoh for gracing the occasion with their esteemed presence and for sharing their insightful and inspiring words with the gathering.

She extended heartfelt thanks to Prof. Indrajit Dube, Vice Chancellor of NLU Meghalaya, for his constant support, visionary leadership, and encouragement to the students and organizing team.

Professor Dhakar also acknowledged the efforts of the faculty members, organizing committee, administrative staff, student volunteers, and especially the Moot Court Society, whose commitment and coordination made the event a success.

With warm wishes to all the participating teams and a note of appreciation for the vibrant legal discourse that the competition aims to foster, she brought the inaugural function to a close, leaving the audience with a sense of anticipation and excitement for the rounds ahead.

Following the Vote of Thanks, the ceremony transitioned into the official opening of the competition. A specially curated video introducing the moot proposition—crafted with creativity and precision by the members of the Moot Court Society—was played for the audience. The video not only offered a thematic overview of the competition’s problem but also set the tone for the intellectual rigor and nuanced advocacy that would follow.

With the energy in the hall high and anticipation in the air, Ms. Jyotishikha Rajkashyap, Convenor of the Moot Court Society, formally declared the 2nd NLU Meghalaya National Moot Court Competition, 2025, open. Her words, marked by pride and purpose, reflected the months of hard work poured into the planning and execution of the event.

The inaugural ceremony concluded with a renewed sense of excitement and motivation as teams prepared to embark on the challenging rounds ahead, ready to engage, argue, and advocate.

12:30 PM | Researcher Test | UG Block

With the inaugural ceremony concluded, the competitive spirit took center stage as the began in full swing.

At 12:00 PM, the Researchers’ Test was conducted in the designated hall. This written round was designed to evaluate the depth of legal research, conceptual clarity, and understanding of the moot proposition by the researchers from each team. The test served as a vital component of the competition, emphasizing the importance of behind-the-scenes legal scholarship that supports oral advocacy.

Simultaneously, the Drawing of Lots took place, wherein all participating teams gathered for the announcement of their preliminary round matchups. Conducted under the supervision of the Moot Court Society to maintain complete transparency, the drawing of lots revealed the sides (petitioner/respondent) each team would represent and their respective opponents. This moment brought a wave of excitement and anticipation as participants began strategizing for their oral rounds.

Alongside these events, a detailed Judges’ Briefing Session was conducted by representatives of the Moot Court Society. This session ensured that the esteemed panel of judges—comprising legal professionals, academicians, and practitioners—were well-versed with the rules, scoring criteria, time allocations, and expectations of the competition. The briefing allowed for clarity and uniformity in adjudication, a critical factor in ensuring the highest standards of fairness throughout the competition.

With all formalities complete, the stage was set for the preliminary rounds, as teams braced themselves to argue, persuade, and excel.

03:00 PM | Preliminary Round-I| UG and PG Block

Court Hall-I

In the proceedings, the Petitioner, Flash Retail Pvt. Ltd., began by defending its innovative practices, including personalized pricing and location-based service optimization. They argued that these features enhance user experience, ensure timely delivery, and are implemented with user consent in compliance with the Digital Personal Data Protection Act. Flash Retail maintained that their algorithm-driven pricing models were transparent and did not amount to any unfair trade practice under Section 20 of the Consumer Protection Act.

They emphasized that their business model is inventory-based, yet it functions within the FEMA framework and complies with FDI policies, which do not explicitly restrict their current operations. To show good faith, they even agreed to alter their marketing tagline from “10-Minute Delivery” to “Lightning Speed” to avoid any potential misrepresentation. They asserted that any regulatory actions targeting them would infringe on their Article 19(1)(g) rights to practice any profession or carry on any occupation, trade, or business.

In response, the Respondents, Union of Sindhupradesh & Ors., raised serious concerns over Flash Retail’s operations. They alleged that Flash Retail’s practices lacked transparency, especially in how customer data was tracked and used without explicit, continuous consent. The Respondents contended that the location-tracking algorithms, while claimed to be for operational efficiency, breached consumer privacy norms, especially when such tracking persisted even after app usage.

Further, they pointed to market dominance concerns, highlighting Flash Retail’s 45% market share, and argued this amounted to a dominant position, potentially stifling competition. They alleged that such a model facilitated predatory pricing and discriminatory trade practices. They invoked Sections 3 and 4 of the Competition Act, claiming that Flash Retail’s agreements with select sellers amounted to foreclosure of competition.

The Bench questioned Flash Retail on the necessity of constant location tracking and how it aligned with privacy obligations. In turn, they questioned the Respondents about the legitimacy and clarity of their allegations, especially in the absence of conclusive proof of consumer harm.

In rebuttal, Flash Retail reiterated that regulatory scrutiny should not penalize innovation, especially when consumers benefit. They cited precedents, including Domestic Pvt. Ltd. v. Union of India, to argue that retrospective restrictions on lawful business activities—like theirs—could endanger economic freedom and digital growth.

The court appeared focused on balancing the dual interests of regulating emerging digital marketplaces and safeguarding consumer rights, signaling that any ruling would need to establish boundaries without stifling innovation or violating constitutional protections.

Court Hall-II

In Courtroom 2, the Petitioners opened with a robust challenge against the investigation order, citing that it violated principles of natural justice and lacked merit under Section 26(1) of the Competition Act, rendering it void ab initio. Arguing that the Competition Commission of India (CCI) had overstepped its jurisdiction by delving into data privacy concerns, the counsel referenced the landmark case of Harshit Chawla v. WhatsApp Inc., advocating for a strict interpretation of regulatory boundaries.

Further strengthening their stance, the Petitioners contested the classification of their client as a dominant player in the market. They argued for a broader market definition, encompassing all types of SMS and digital services, making dominance an untenable claim. The Co-counsel then addressed issues related to consumer harm, invoking Matrimony.com Ltd. v. Google, to demonstrate that the client’s data sharing practices and ‘take-it-or-leave-it’ policies lacked anti-competitive effect.

In response, the Respondents mounted a firm defense, affirming the CCI’s jurisdiction with reference to CCI v. Jindal Steel, and dismissing the appeal against investigative orders as procedurally unfounded. Emphasizing restrictive trade practices, they invoked doctrines of coercion and unconscionable contracts and argued how certain practices could distort competition if left unchecked. The judges probed deeply, especially on the nuances of market definitions and statutory interpretations.

Rebuttals were sharp: the Petitioners insisted that voluntary data consent and market alternatives undercut any claim of abuse, while the Respondents reiterated procedural legality and public interest. The bench remained actively engaged, with arguments on statutory overlap and consumer protection steering the discussion.

Court Hall-III

Courtroom 3 saw a compelling exchange of arguments in the first round as the Petitioner and Respondent teams debated core issues surrounding misleading advertisements, algorithmic pricing, and consumer protection. The discussions largely revolved around the interpretation of consumer rights under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, and the obligations of e-commerce platforms in ensuring fair trade practices.

The Petitioners raised concerns about deceptive marketing tactics, particularly the “10-minute delivery” claim, questioning its feasibility and potential to mislead consumers. They also explored how personalized pricing models may violate the principle of transparency, potentially harming consumer trust.

The Respondents defended their client’s business model, arguing that marketing strategies are backed by clear terms and conditions and that algorithmic pricing operates on demand-supply logic, not with the intent to exploit. They emphasized compliance with statutory provisions and framed their position within the evolving landscape of digital commerce and innovation.

Though the round had limited material facts shared, it reflected the broader tensions between market efficiency and legal accountability, a recurring theme throughout the competition.

Court Hall -IV

In Courtroom 4, the proceedings focused heavily on the Competition Act, specifically addressing unfair trade practices and concerns related to consumer protection. The Petitioner argued that Flash Retail’s dynamic pricing strategy, driven by demand, was legitimate and fell well within market norms, citing the Competition Act’s provisions on pricing flexibility. They maintained that pricing adjustments were essential for maintaining competitiveness in the e-commerce sector and that the Consumer Protection Act should not be invoked unless there was clear evidence of deceptive practices. The Petitioner contended that discounts and offers were integral to market behavior and argued that companies like Flipkart and Amazon regularly engage in similar pricing models, which have not been questioned by authorities in the past.

The Respondent, however, countered by asserting that the pricing practices of Flash Retail raised concerns under Section 4 of the Competition Act and could potentially lead to anti-competitive conduct. They emphasized that the dynamic pricing strategy could create an unfair advantage in the market, thus leading to consumer harm. They pointed out that, under Section 27 of the Companies Act, there are clear restrictions on business conduct that would otherwise distort competition and violate consumer rights. The Respondent also referenced Nakara v. Union of India, citing the case’s principle about exclusive practices that harm broader market access.

The court intervened to clarify that Article 19(1)(g), which guarantees the right to trade, should not be construed as absolute but instead subject to reasonable restrictions. The judges pointed out that, while businesses are entitled to operate freely, regulations can be imposed if there is clear evidence of unfair practices that harm public interest. The Petitioner concurred, agreeing that the investigation should proceed without judicial intervention at this stage. The Respondent argued that, once completed, the investigation would reveal whether Flash Retail’s conduct violated competition law or was consistent with fair trade practices

Court Hall-V

The Petitioners and Respondents clashed over the legality and ethics of FlashRetail Pvt. Ltd.’s 10-minute delivery model. Representing the Petitioners, the counsel began by invoking the principle of natural justice—audi alteram partem—asserting that the investigation initiated lacked fair hearing and challenging its validity under the Competition Act. The Petitioners argued that past business practices of FlashRetail cannot be judged retroactively based on new regulations and defended the company’s algorithm-driven services as responsive to post-pandemic market demand.

Crucially, the Petitioners raised Issue 2, challenging the restriction on online-only businesses under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of Sindhu Pradesh, asserting that such limitations unfairly curtail the right to trade and must pass the test of reasonable restriction. Citing State of Bombay vs R.M.D. Chamarbaugwala and State of Rajasthan vs Hindustan Sugar Mills Ltd., they emphasized the company’s compliance with FEMA and defended their model as one of innovation, not exploitation.

Taking the floor next, the Respondents countered with arguments rooted in public safety and socio-economic justice, emphasizing that the 10-minute delivery scheme exerts dangerous systemic pressure on gig workers. They cited Article 21, raising concerns about worker rights and linked the model to rash and negligent driving, invoking State of Gujarat vs Mirzapur Moti Kureshi to stress that the right to trade cannot endanger lives.

Further, the Respondents highlighted non-compliance with zoning laws through the proliferation of unregulated dark stores, and violations of Rule 5(4) of the Consumer Protection (E-Commerce) Rules, 2020, arguing that exaggerated promises mislead consumers. They underscored that such business models exploit regulatory loopholes while violating constitutional safeguards.

In rebuttal, the Petitioners reiterated the voluntary nature of services and the presence of alternative delivery options, refuting allegations of coercion or harm. They defended the company’s regulatory compliance and clarified that innovation in service delivery, when accompanied by safeguards, should not be penalized.

The session ended with a flurry of judicial questions probing the limits of constitutional freedoms, consumer protection, and ethical entrepreneurship—leaving the audience eager for how this nuanced legal battle would unfold in the next rounds.

Court Hall -VI

The first round of arguments centered around the complex interplay between consumer rights, competition law, and constitutional protections in the context of the ultra-fast delivery model promoted by Flash Retail.

The Petitioners opened their case by asserting that informed consent had been duly taken from the consumers, especially regarding the use of data and algorithm-driven customization of prices. Emphasizing consumer autonomy, the counsel argued that transparency was maintained, and the terms and conditions were clearly mentioned on the platform.

The Respondents, however, raised fundamental constitutional and competition law objections. They began by arguing that only Indian citizens could invoke Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, which protects the right to practice any profession or carry on any occupation, trade or business. This statement came in light of Flash Retail allegedly being a foreign-funded entity operating in the Indian market.

A critical issue raised by the Respondents was the intense operational pressure placed on gig workers. Citing the 10-minute delivery promise, it was submitted that delivery agents are often forced to overspeed and compromise their safety, all in a bid to meet unrealistic timelines. This, they argued, reflects poorly on the ethics of the business model.

Delving into the market implications, the Respondents claimed that Flash Retail occupies a dominant position in the market. They argued that due to heavy backing by foreign investors, the platform offers 10–20% additional discounts, making it impossible for offline retail shops, which lack such backing, to compete. The Respondents submitted that such practices amounted to abuse of dominant position under the Competition Act, 2002.

Perhaps the most controversial argument was the claim that Flash Retail is allegedly funded by the FBI, with an intention to wipe out domestic competitors—a claim aimed at questioning not just the economic intent but the national interest implications of foreign-backed digital enterprises. The Respondents termed this an unhealthy and illegal market practice, urging the Bench to consider the broader ramifications of such market behavior on the Indian economy.

Court Hall -VII

The Respondents began by addressing key constitutional concerns, arguing that Article 14 was not violated by their platform’s operations or business model. Responding to allegations related to over-speeding by delivery personnel, they submitted that such concerns fall under the purview of the Union Government of India and not the individual company, shifting the responsibility for safety regulation away from private platforms.

One of the pivotal moments came when the Bench questioned whether adopting stricter globalized laws would hinder India’s economy, and whether India should resist or embrace the wave of globalization. The Respondents acknowledged the global trends but clarified that their model aimed to support local markets and emphasized that the rights of small “brick-and-mortar” retailers were being violated by platforms engaging in aggressive digitization and discounting tactics.

Another significant contention was the Respondents’ argument that the Enforcement Directorate (ED)—which had allegedly initiated proceedings or inquiries—is a quasi-judicial body and not a regulatory authority, thereby limiting its jurisdiction in overseeing pricing models or consumer impact.

The Respondents further raised serious concerns over consumer privacy, stating that constant location tracking and the use of dynamic price tagging by Flash Retail and similar platforms could result in price discrimination among customers, leading to economic inequality and market distortion.

Overall, the courtroom witnessed intense exchanges highlighting the conflict between innovation and fairness, and between digital expansion and constitutional morality, making it a key round that merged public policy, legal doctrine, and technological ethics.

Court Hall -VIII

The Petitioner began by arguing that Flash Retail had adhered to all legal and regulatory frameworks, emphasizing that the company’s marketing strategies, particularly the “10-minute delivery” claim, were not misleading but rather an integral part of their business model. The Petitioner stressed that Flash Retail operated within the bounds of the law, and the claims made about delivery speed were reasonable and based on genuine operational capabilities. They also contended that the investigation initiated by the authorities was unwarranted, as no substantial evidence had been presented to support the claims of unfair trade practices.

The Respondent, on the other hand, contended that the “10-minute delivery” claim was a misrepresentation, qualifying it as a marketing gimmick aimed at misleading consumers. They cited the Gauri Shanker case, where it was established that the constitutionality of laws passed by the government cannot be questioned by the courts, arguing that judicial interference in matters of regulation was inappropriate. The Respondent further invoked Section 26(1)(a) of the Competition Act, stating that once the Central Government referred an investigation, it was non-challengeable.

The Petitioner countered these assertions by emphasizing that the investigation was a disproportionate response to a marketing claim, suggesting that no harm had been done to consumers or the marketplace. The Respondent, however, argued that Flash Retail’s operations were in violation of Article 21 of the Constitution, claiming that the company’s practices could infringe upon consumer privacy and data protection laws.

The court questioned both parties on the matter of judicial intervention and whether the investigation process was being properly followed. The Respondent asserted that investigations fell under administrative jurisdiction, and the court had no grounds to interfere at this stage. They also referenced Section 26(1)(a) to argue that any challenges to the investigation were unfounded.

As the hearing continued, the judges deliberated on whether the “10-minute delivery” claim could truly be classified as misleading or whether it was simply part of a legitimate business strategy. The debate shifted towards whether Flash Retail’s marketing and business practices were in line with consumer protection regulations and constitutional rights.

The session concluded with both parties having made their cases, and the court reserved its judgment on whether the investigation would proceed and if Flash Retail’s business practices warranted any changes.

Court Hall- IX

The Petitioner began by addressing the concerns raised regarding Flash Retail’s pricing and delivery practices. The Petitioner emphasized that the ultimate decision to purchase products rests with the consumer, with no strict mandates from the company to compel purchases. They clarified that the 10-minute delivery guarantee, while ambitious, is feasible, and any delays are due to unforeseen circumstances. They sought to excuse these instances as a result of operational challenges rather than intentional failure. The Petitioner also highlighted that long-time customers receive additional benefits and discounts through the app, arguing that such offers do not constitute unfair trade practices under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019.

When questioned by the judge about the e-commerce companies’ ability to control pricing and stock levels, the Petitioner responded that it is not feasible for the company to manage a warehouse or set fixed prices due to the dynamic nature of e-commerce. They further argued that discounts are an accepted marketing strategy and should not be construed as unfair trade practices. In response to concerns about algorithmic decision-making in pricing and data usage, the Petitioner assured the court that users have control over their app’s algorithmic functions, though certain backend algorithms are not disclosed for security reasons. They also asserted that competitors could not misuse their data if it were to be shared.

The judge raised concerns about e-commerce companies’ capacity to control stock and prices given their business models. This led to a discussion about the permissibility of discounts and whether such practices violate consumer rights or distort the market.

Court Hall-X

The proceedings in Courtroom 10 commenced with the Petitioner’s counsel confidently laying down the foundation of their case, asserting that the company’s operations are in full compliance with the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) and warehousing regulations. Stressing a strong adherence to the statutory framework, the counsel maintained that no breach of legal obligations had occurred and that the Respondents’ allegations were unfounded.

The Petitioner advanced a compelling constitutional claim, arguing that placing undue restrictions on e-commerce entities constitutes executive overreach and violates Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, which safeguards the right to practice any profession or carry out any occupation, trade, or business. According to the counsel, the regulatory interference not only threatens innovation and fair competition but also discourages entrepreneurial spirit in the rapidly evolving digital economy.

They emphasized that the restrictions proposed by the state were disproportionate and arbitrary, and lacked a justifiable nexus to the intended objective of public welfare. In doing so, the Petitioner framed the case as one of economic freedom versus excessive control, where the scales must tilt in favor of liberalized growth and legitimate enterprise.

During the submissions, the bench intervened with pointed queries, most notably questioning the absence of dominance by the Petitioner’s client in a market where they are evidently a key player. The judges pressed the counsel on market definition, concentration levels, and the implications of unchecked market power, setting the tone for a deeper inquiry into competition law and abuse of dominance in the upcoming arguments.

The courtroom remained attentive as the Petitioner skillfully navigated constitutional and economic angles, setting the stage for an equally vigorous response from the Respondents.

05:30 PM | Preliminary Round-II| UG and PG Block

Court Hall -I

As the debate unfolded between the parties, the spotlight was on the complex dynamics of quick commerce, AI surveillance, and constitutional freedoms. The case centered around the legitimacy and ethicality of 10-minute delivery models, algorithmic tracking, and pricing practices in the digital marketplace. Speaker 1: Petitioner’s Stand – Defending Innovation and Business Rights

The Petitioner’s speaker began by firmly establishing that the company under scrutiny does not directly operate any warehouses, nor does it prohibit inventory ownership. Instead, it employs AI-driven operational models tailored to locational logistics, emphasizing efficiency without infringing on legal boundaries.

Addressing concerns over alleged frauds, the Petitioner clarified: “There has been no evidence of fraudulent intent or activity. The promise of 10-minute delivery isn’t always feasible, and customers are transparently offered alternative benefits.”

Things got intense when the Hon’ble Judge inquired:

“What is the doctrine of legitimate expectations?”

To which the counsel tactfully responded, highlighting that customers reasonably expect swift service, and a blanket ban on quick delivery would be contrary to those legitimate consumer expectations.

On the issue of data privacy, the bench questioned:

“By using algorithmic tools to track data, even when customers aren’t actively using the service—aren’t you breaching their privacy?”

The Petitioner’s reply was strategic:

“Tracking is done to avoid repeated location access requests, enhancing customer convenience rather than violating their privacy.”

Citing Article 19 of the Constitution, the counsel stressed that a complete ban on the 10-minute model would directly interfere with the company’s right to carry on trade. They further argued that e-commerce is inherently more adaptable, and any restriction exclusively on this sector would be discriminatory.

Touching upon pricing strategies, the speaker defended the company’s discount practices, stating:

“Our pricing is competitive, not predatory. Both online and offline markets should be viewed as substitutable.”

They also invoked Section 4 of the Consumer Protection Act, asserting no market dominance, and emphasized that higher market share alone cannot define dominance, especially in a diversified competitive environment.

They contended that these strategies weren’t just innovative—they were manipulative, creating entry barriers and damaging market integrity.

“Such exclusive personalized offers distort fair pricing mechanisms and erode equal market opportunity,” the Respondent asserted.

According to the Respondent, while the tech might seem benign, its implications are far-reaching:

“By hyper-targeting customers and controlling prices through location-based forecasting, the company is not just competing—it’s dominating.”

They argued that this went beyond healthy competition and entered the zone of predatory pricing and data-driven exclusion, meriting regulatory intervention.

Court Hall -II

The core of the Respondent’s case centered on allegations of market domination, discriminatory pricing, and anti-competitive behavior, particularly in the context of FlashRetail’s expansion into the B2C sector.

The Respondent began by claiming that FlashRetail is effectively dominating the two preferred sellers on its platform, using demand forecasting as a tool to tilt the market in its favor. They stressed the need to focus on the substance of these practices, arguing that FlashRetail is not merely engaging in competitive business but is discriminating against competitors in ways that are harmful to the market.

They also pointed to foreign exchange rules, which they argued, set caps on foreign investment and stated that e-commerce companies should operate only on inventory-based models. This assertion formed part of a broader argument that FlashRetail business model violates these rules, as they are not operating on an inventory-based venture and are instead engaging in practices that undermine the spirit of those regulations.

Further, the Respondent contended that the government has the authority to impose rules if there are loopholes in e-commerce operations, and in this case, FlashRetail is exploiting those gaps. Specifically, they raised concerns about price mechanisms and how they violate the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) policy. They also pointed to an investigation by the Enforcement Directorate (ED), which found that FlashRetail use of location-based pricing is discriminatory and tilts the market in its favor.

In addition, the Respondent highlighted that while FlashRetail operates as a B2B business, it is actively trying to enter the B2C market, creating an unfair advantage through its exclusive dealership agreements. They claimed that these agreements effectively prevent sellers from competing and exclude potential competitors from the market, thereby foreclosing competition.

Referring to Sections 3 and 4 of the Competition Act, the Respondent argued that FlashRetail business practices constitute anti-competitive conduct, particularly the foreclosure of competition by engaging in exclusivity and preventing competition from emerging.

The Respondent further accused FlashRetail of engaging in autonomous algorithmic pricing, which they argued is a deliberate and hidden abuse of market power. They emphasized that algorithmic pricing—which is often opaque—allows FlashRetail to manipulate prices and obscure the true nature of its competitive preferences, making it impossible for other businesses to operate on a level playing field.

The core of the Respondent’s argument was that the abuse is hidden in the algorithms, which function in a way that conceals discriminatory behavior and undermines fair market practices. The court is now left to consider whether FlashRetail use of AI, location-based pricing, and exclusivity agreements constitutes a breach of competition laws and if such practices are fair in an increasingly digital and globalized economy.

Court Hall -III

The Petitioner defended FlashRetail operational model, addressing concerns over driver safety, dynamic pricing, and allegations of misleading practices. The Petitioner began by highlighting recent updates to their app, which included a 50-rupee discount for customers, a move aimed at improving the service experience and enhancing customer satisfaction.

The discussion took a turn when the Hon’ble Judge raised an important query regarding the safety of drivers, particularly in the context of the company’s rapid delivery model. “What if there are accidents involving the drivers?” the Judge asked, concerned about the potential risks to delivery personnel.

In response, the Petitioner’s counsel assured the bench that adequate insurance policies are in place to cover driver safety. These policies, they stated, are designed to protect drivers in the event of accidents and comply with all relevant safety regulations. The counsel further emphasized that FlashRetail is committed to updating their safety guidelines as per evolving standards and regulations, demonstrating an active effort to ensure the well-being of their workforce.

Turning to the issue of innovation, the Petitioner argued that the company’s model is being unfairly targeted due to its success in delivering products to customers’ doorsteps quickly. They asserted that FlashRetail is merely trying to innovate and improve delivery speeds, not undermine the competitive market or the safety of workers.

Addressing concerns about dynamic pricing, the Petitioner strongly defended the company’s use of algorithmically driven pricing strategies, stating that these prices are non-discriminatory and designed to serve customer demand without misleading or exploiting them. The counsel highlighted that the dynamic pricing model is based on data-driven insights and does not involve arbitrary price hikes or predatory pricing practices.

In essence, the Petitioner’s defense focused on FlashRetail commitment to safety, fair pricing, and innovation, asserting that their business practices align with industry standards and regulations. The court will now evaluate whether these claims hold up against the allegations of unfair competition and safety risks posed by the rapid delivery model.

Court Hall-IV

The Respondent challenged the Petitioner’s claims of rights infringement and defended the legality of their pricing mechanisms. The Respondent began by asserting that the Petitioner’s rights are not being infringed under Article 14 (equality before the law) and Article 19 (freedom of speech and expression). They argued that there is no misuse of algorithmic pricing by the company, asserting that FlashRetail pricing model is transparent, non-discriminatory, and follows all relevant legal and ethical standards.

Further building on their argument, the Respondent pointed out that Sections 3 and 4 of the Competition Act govern unauthorized exchanges of funds in the market, and these provisions do not apply to the situation at hand. The Respondent emphasized that pricing mechanism does not violate these provisions and should be considered within the framework of fair market competition.

In a direct counter to concerns over market manipulation, the Respondent referenced Article 19(6), which allows for reasonable restrictions on the freedom of business and trade in the interest of public welfare. They argued that any regulatory measures taken against the company must align with this reasonable restriction clause, ensuring that public interest is always at the forefront of legal assessments.

The tension escalated when the Hon’ble Judge raised a fundamental question: “In this case, what is the public interest?” The court sought to understand whether the actions align with societal welfare or serve solely the interests of the business and its consumers. This query set the stage for the next round of arguments, as both sides now had to clarify how their positions serve the public interest—whether in terms of consumer protection, fair competition, or business innovation.

Court Hall-V

The Respondent raised significant concerns regarding unfair trade practices and data privacy violations allegedly committed by FlashRetail. The Respondent argued that it is engaging in practices that not only undermine consumer trust but also violate data protection laws.

The Respondent began by accusing the Petitioner of unfair trade practices, specifically pointing to instances where FlashDetails’ business operations have been opaque, leaving consumers at a disadvantage. They stressed that FlashDetails claims to offer transparency, but in reality, the company has failed to live up to this promise, especially concerning data privacy.

A major part of the argument focused on data privacy concerns, with the Respondent highlighting instances where personal customer data had been leaked to third parties without proper notification. They emphasized that this constitutes a serious violation of privacy laws, as users were not notified of the data breach, which directly undermines trust in the platform.

The Respondent also brought attention to the fact that FlashRetail operations infringe upon the provisions of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPA), particularly Section 8, which requires that the data processor must ensure proper data protection for its users. The counsel argued that the failure to secure consumer data constitutes non-compliance with data protection obligations.

Moreover, the Respondent pointed out that the Terms and Conditions (T&C) governing the use of FlashRetail platform were not clearly stated or sufficiently transparent for consumers, which could lead to misunderstanding and misuse of personal data. This lack of clarity, they argued, is another unfair practice that exploits consumers and undermines their rights.

Court Hall-VI

The Petitioner defended Flash Retail’s practices, arguing that the company’s advertising claims, including the “10-minute delivery” guarantee, were not misleading. The Petitioner clarified that the term “10-minute delivery” was a marketing strategy aimed at enhancing customer comfort, and the delivery time was contingent on several factors, including unforeseen circumstances. They further explained that the company removed the tagline in response to changing circumstances, replacing it with “lightning-fast delivery,” which was more in line with the service being offered.

Addressing the issue of consumer rights, the Petitioner cited the doctrine of frustration, stating that in cases where unforeseen circumstances affect delivery timelines, the contract may be voided. Asserting that Flash Retail’s intent was never to deceive, the Petitioner argued that the compensation offered to consumers for delays was a gesture of goodwill. Additionally, they clarified that Flash Retail’s terms and conditions outlined that consumers could expect compensation if the promised delivery time was not met.

The Petitioner also discussed the impact of the company’s marketing strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing that it helped maintain consumer confidence during a difficult period. When questioned by the Judge about the meaning of the word “guarantee” in this context, the Petitioner explained that it was used as part of a broader marketing strategy to reassure customers, in accordance with their terms and conditions.

Regarding the anti-competition concerns, the Petitioner highlighted that Flash Retail held only a 45% market share, refuting claims of market dominance or anti-competitive behavior. They emphasized that the company’s practices were in line with market norms and that no unfair advantage was being gained by Flash Retail.

The Judge also raised concerns about the promotional material used in the market and whether it could potentially violate anti-competition laws. The Petitioner maintained that the marketing strategies were legal and aimed at fostering competition, rather than suppressing it.

Court Hall-VII

The session in Courtroom 7 was marked by sharp judicial scrutiny following the presentations from both sides. After hearing the arguments, the judges directed a pointed line of questioning to the Respondents, focusing on the alleged discriminatory treatment between foreign-funded and domestic companies.

The Bench asked whether the Union of India can lawfully differentiate between companies under Article 14, especially in the context of FDI regulations and market entry provisions. The judges specifically questioned, “Can the Union differentiate between two companies based solely on their source of funding? And if so, on what constitutional basis?”

In response, the Respondents referred to Articles 14 and 19(1)(g) and contended that reasonable classification is permissible under the Constitution. They argued that distinctions may be made in the public interest, citing policy-based reservations and national interest as justifications for treating companies differently, particularly in the context of safeguarding small retailers and ensuring balanced competition in the domestic market.

The judges pushed further: “If a company enters India, can the government invoke national interest to justify differential treatment? Is this not discrimination?” The Respondents reiterated that such policy distinctions are permissible when backed by legitimate state objectives, including economic protectionism, consumer welfare, and fair market practices.

In rebuttal, the Petitioners took issue with the pricing structure of the opposing party, refuting the claim that their pricing was arbitrary or discriminatory. They asserted that the pricing model was based on objective criteria such as supply-demand dynamics, and thus did not violate Article 14.

The round concluded with the Bench probing the limits of state intervention in commercial affairs, leaving both teams to defend their stance on the constitutionality of market regulation and economic classification.

Court Hall -VIII

The second round in Courtroom 8 began with the Petitioners presenting their arguments, during which the Bench quickly turned its attention to the issue of jurisdiction. The judges questioned the maintainability of the petition under Article 32 of the Constitution, asking why it had been directly brought before the Supreme Court. The Petitioners responded that the matter invoked Articles 14 and 19(1)(g), contending that the rights to equality and the freedom to practice any profession or trade had been violated. However, this justification did not entirely satisfy the Bench, which expressed concern over the lack of substantive reasoning behind invoking Article 32.

The Petitioners also emphasized that informed consent had been taken from customers, and that the algorithm-based pricing and delivery models used by Flash Retail were compliant with consumer expectations and transparency norms. They maintained that Flash Retail’s operations were legally sound and denied any form of misleading advertisements.

The Respondents, however, raised significant objections. They argued that only citizens can claim protection under Article 19(1)(g) and that the petitioner, being a company, could not invoke this right. They went on to allege that Flash Retail, due to its dominant market position, was engaged in unfair trade practices. It was argued that Flash Retail offered 10–20% deeper discounts, which amounted to an abuse of dominance under the Competition Act and was funded by foreign entities (including claims of FBI funding) with the intent to eliminate smaller competitors—a practice the Respondents described as detrimental to a healthy market environment.

In support of their case, the Respondents also highlighted that offline retailers lacked similar financial backing and therefore could not compete with the aggressive pricing strategies of Flash Retail. Furthermore, they raised serious concerns about the mental and physical stress faced by delivery drivers, asserting that the 10-minute delivery promise pressured drivers into overspeeding and unsafe practices.

Despite exceeding the allotted time, the Petitioners took an additional 6–7 minutes to conclude their submissions, which appeared to test the patience of the Bench. The judges remained sharply focused on constitutional maintainability and public interest concerns.

Court Hall -IX

The Petitioners began by addressing the evolving framework of consumer protection, particularly in the context of the gig economy and 10-minute delivery models. It was argued that while the concept of ultra-fast delivery was promoted, such claims were merely average estimates, not guarantees. The Petitioners defended this strategy as a marketing tool used to attract customers and a clarified that terms and conditions always accompanied such claims.

They further argued that any failure to deliver within 10 minutes should not be construed as a breach, especially since compensation policies were clearly in place, and added that Flash Retail had already altered its branding from “10-minute delivery” to “lightning-fast delivery” to avoid misleading interpretations. Citing the landmark judgment of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India, the Petitioners emphasized the importance of informational privacy and clarified that while algorithms were used, these were not arbitrarily set, but rather driven by demand and supply logic, not designed to exploit users.

The Bench engaged closely with the second issue in the proposition, particularly on the use of the word “guarantee” in government-backed proposals. The judges inquired: “What does the word ‘guarantee’ mean in this context? Can it be upheld as a binding claim?” The Petitioners responded that the term was used for consumer comfort, not as a contractual obligation. They reiterated that if a delivery could not be completed within 10 minutes, the platform offered remedies like refunds or vouchers, which amounted to fair conduct.

Further, the judges pressed the Petitioners on whether such claims were anti-competitive, especially during periods like the COVID-19 lockdown. In response, the Petitioners submitted that these strategies were necessary and beneficial during the pandemic and served as public interest initiatives rather than anti-competitive conduct.

The arguments ultimately highlighted the fine balance between aggressive marketing, consumer welfare, and legal compliance, with the judges keenly evaluating how innovation must be tempered with accountability.

Court Hall – X

The Petitioner presented arguments focused on the evolving gig economy and its relevance to social security for gig workers. Citing the proposition, the Petitioner emphasized that the gig economy is a new concept, and with the advent of the ordered economy, there is a need to ensure proper regulations for gig workers. The Petitioner further argued that the gig economy holds significant potential for employment and economic flexibility, ensuring benefits for both the workers and consumers.

The Judge raised a pertinent question regarding transparency in this context, asking, “What transparency exists in this case?” In response, the Petitioner clarified that, with regard to the allegations of misleading advertisements, the 10-minute delivery time referenced is not a strict guarantee but an average time. The Petitioner explained that geographical factors, such as location and traffic conditions, often influence the delivery time, and in certain areas, even a two-minute delivery time is achievable.

The Judge also inquired about the claim regarding personalized pricing and how it affects consumers. The Petitioner defended the use of personalized pricing algorithms, arguing that these pricing models are based on supply and demand dynamics, a standard practice in the e-commerce sector. They stressed that personalized pricing is not meant to disadvantage consumers but rather to ensure efficiency and competition within the market.

The Petitioner also addressed concerns about privacy rights and algorithm transparency, explaining that while the algorithm may be complex and not easily understandable by a layperson, its purpose is to create a balance between demand and supply. The Petitioner argued that there is no violation of individual privacy rights, as the algorithm operates within the legal bounds and is aimed at enhancing the overall consumer experience. They further asserted that the private nature of these algorithms does not infringe upon the rights of individuals, as the data used is in compliance with existing privacy laws.

In summary, the Petitioner contended that the gig economy, along with the use of personalized pricing and algorithms, is a necessary and evolving feature of modern commerce, with safeguards in place to ensure fairness, transparency, and respect for privacy.

TEAMS QUALIFYING FOR THE QUARTER-FINAL ROUNDS ARE

TC-2504

TC-2503

TC-2520

TC-2515

TC-2512

TC-2511

TC-2501

TC-2516

26th April 2025 (Day-2)

10:00 AM | Quarter Final Rounds| UG Block

Court Hall-I

The parties appeared before the Hon’ble Bench for the Quarterfinal round. After taking the permission of the Bench, the counsel for the Respondent Speaker 2 began with the matter of Harshita Chawla v. WhatsApp, differentiating between inventory market models and transitional shops. The Judges questioned whether the Respondents were implying employees as gig workers and sought clarification on the scope of inventory and predatory pricing. When the Judges posed that if consumers find prices high, it is simply their choice not to buy, the Speaker responded that the algorithm impacts pricing patterns and referred to the annexures, adding that adding insurance does not amount to influencing the market.

Following this, Respondent Speaker 1 advanced submissions, referring to Ashok Kumar v. Union of India, asserting that corporate structure alone cannot justify intervention. The Bench heavily questioned the jurisdiction, asking whether the matter involved a question of law or a fundamental rights violation under Article 32. The Judges expressed concern about how the Petitioner directly approached the Supreme Court while the investigation was still pending, without exhausting the remedy at the High Court level. The Judges introduced the concept of “Red Herring” and grilled the Speaker regarding the difference between “control” and “handle,” indicating the need for a clear demarcation.

The Bench emphasized that privacy is a part of fundamental rights, but questioned whether there was an actual violation sufficient to maintain a writ petition under Article 32. They asked how a potential or speculative threat could be sufficient for invoking the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court. The Speaker responded that mere apprehensions cannot form the basis of constitutional challenge and emphasized that proper legal backing, not just political arguments, must be provided.

The Judges further questioned about interim relief, stressing that the Court must be cautious when an investigation is still at a preliminary stage and proper forum procedures had not been exhausted. The proceedings in Courtroom 1 thus reflected rigorous judicial engagement on the jurisdictional, constitutional, and procedural grounds concerning privacy rights and the platform’s conduct.

Court Hall-II

The quarterfinal round in Courtroom 2 commenced with the Petitioner’s Speaker 1 representing Flash Retail Pvt. Ltd. presenting arguments on Issues 1, 2, and 3. Speaker 1 began by defending the legality of Flash Retail’s business model, asserting that it operated strictly as a marketplace model in accordance with Clause 1 of the FDI Policy. It was clarified that the platform merely connects buyers and sellers and provides delivery services without exercising control over the goods sold. Addressing concerns raised by the Bench regarding the limited number of sellers on the platform, the speaker referenced the FDI regulations to clarify that the number of sellers does not automatically render a platform inventory-based unless there is demonstrable control.

On regulatory proceedings, the speaker emphasized that Flash Retail remained fully compliant with all regulatory bodies, and no final orders had been passed against it. Moving to Issue 2, the speaker argued that the proposed minimum pricing regulations constituted unreasonable restrictions on the right to practice any profession under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution. Highlighting the essential nature of ultra-fast delivery services in the post-COVID era, the speaker asserted that innovation should not be curtailed without compelling justification. Addressing concerns regarding delivery worker safety, the speaker responded that gig workers were not direct employees of the platform and thus not relevant parties to the present dispute.

On Issue 3, regarding pricing models and alleged market dominance, the speaker contended that offering discounts is a standard market practice and not indicative of predatory behavior. It was asserted that sellers retained autonomy in pricing decisions, and that algorithms were guided by consumer behavior rather than manipulative pricing strategies. Citing Neeraj Shukla v. CCI, the speaker reiterated that dominance by itself is not unlawful unless accompanied by abusive conduct.

Speaker 2 for the Petitioner addressed Issues 4 and 5, rebutting allegations concerning dark patterns and data privacy violations. It was submitted that Flash Retail’s website features were designed for consumer convenience and did not fall within the definition of dark patterns as recognized by guidelines under the Consumer Protection Act. On privacy concerns, the speaker affirmed compliance with the Digital Personal Data Protection guidelines, stating that only essential data was collected and robust cybersecurity measures were implemented.

In a friendly gesture during the intense exchanges, the Bench reminded the speakers to stay calm and composed, encouraging them to explain their arguments clearly and reassuring them that the Court was there to listen patiently.

Speaker 1 for the Respondents commenced by challenging the jurisdiction of the petition, arguing that the court should refrain from interfering in matters of public policy, which fall within the domain of the legislature and executive under the doctrine of separation of powers. Reliance was placed on the decisions in Balko v. Union of India and RG Kar Medical College to emphasize judicial restraint. The speaker cited Premium Reliance v. State of Tamil Nadu to argue that courts should not issue directives on public policy matters. Clarifying on statutory exhaustion, the speaker referred to Cheeranjivi Lal Chaudhary’s case, stressing the necessity of exhausting alternate remedies before invoking writ jurisdiction.

Speaker 2 for the Respondents addressed Issues 1 and 4, alleging violations of FEMA regulations, particularly Rule 15, by Flash Retail. It was contended that with a 75% foreign stake and de facto control over sellers, the platform operated beyond the permitted marketplace model. On Issue 4, the Respondents argued that the deep discounting strategy employed by Flash Retail amounted to predatory pricing, violating Section 4 of the Competition Act. It was submitted that reasonable restrictions under Article 19(6) could be imposed in the public interest to prevent market distortion.

Addressing concerns of dark patterns, the Respondents asserted that features such as basket sneaking and misleading pop-ups constituted deceptive design practices, contrary to guidelines under the Consumer Protection Act. Respondents emphasized that simply modifying a tagline after criticism could not undo the consumer harm already caused. On data protection, the Respondents argued that Flash Retail failed to disclose external cybersecurity audits, raising concerns regarding consumer data handling practices.

In their final prayer, the Respondents urged the Court to uphold the proposed regulatory restrictions, impose minimum pricing frameworks, direct investigation into potential FDI violations, and prohibit predatory algorithmic pricing practices.

The rebuttal rounds witnessed the Petitioners and Respondents questioning each other sharply. Petitioners challenged the Respondents’ interpretation of FEMA violations and minimum pricing impositions, while Respondents questioned the Petitioners’ classification of their business model and compliance with consumer protection norms. The Judges intervened occasionally, seeking precise statutory references and pushing both sides to clarify ambiguities in their arguments.

Court Hall-III

The session commenced with the Petitioners defending Flash Retail’s hyperlocal delivery model, claiming that their close proximity to consumers enables efficient logistics, resulting in deliveries within 10–15 minutes. Counsel clarified that Flash Retail functions solely as a facilitator under the marketplace model defined in Clause 1.1 of the FDI Policy, offering logistics support without owning or managing inventory directly.

When questioned by the Bench about the practical implications of this speed-based model—specifically regarding delivery drivers violating traffic norms—the Petitioners acknowledged isolated incidents but affirmed their commitment to improving dark store infrastructure and delivery mechanisms to ensure public safety and regulatory compliance. They emphasized that such logistics are essential to their innovative service model, particularly in urban areas.

The Bench raised a critical query: “If dark stores are run by independent agencies, why does Flash Retail need to be operationally involved?” The Petitioners maintained that no functional control is exercised over the sellers or dark store operators, and their role is limited to logistical coordination in line with FDI-compliant e-commerce marketplace operations.

Further, one Judge posed a broader policy question: “Is it not fair for the government to protect its citizens and small retail businesses from large, foreign-funded entities like Flash Retail?” Petitioners responded by invoking Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, asserting that their business operations represent legitimate enterprise, and any restriction must pass the test of reasonableness under Article 19(6). They contended that arbitrary limitations based on funding sources or delivery models would stifle innovation and consumer choice.

The Respondents took the floor to challenge the veracity of Flash Retail’s claims. They argued that the “10-minute delivery” narrative is a misleading marketing strategy, not reflective of ground realities, and has led to a misinformed consumer perception. Citing recent CCPA (Central Consumer Protection Authority) guidelines on dark patterns, the Respondents accused Flash Retail of using manipulative tactics like basket sneaking, nagging, and pre-selected add-ons, all of which diminish informed consent and violate consumer autonomy under Section 2(47) of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019.

The Bench sought clarification: “Is basket sneaking an illegal act or merely an unethical design choice?” To this, the Respondents responded that while regulations are still evolving, such practices fall within the unfair trade practices ambit as outlined in Section 2(1)(r) of the Act and are clearly discouraged in CCPA’s 2023 advisory on dark patterns.

Respondents further pressed on the issue of algorithmic personalization, arguing that Flash Retail’s data-driven features amount to discriminatory treatment of users based on opaque profiling. They contended that users must have the right to know and control how algorithms work, as per the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023, which emphasizes transparency and informed consent in data collection and usage.

During the rebuttals, Petitioners countered a key contradiction: “The Respondents claim not to track user location yet offer region-specific product suggestions. Isn’t that inherently inconsistent?” The Bench took note of the observation. Respondents clarified that live tracking is activated only during the delivery phase, strictly for logistical coordination and better communication between customers and delivery personnel.

The round concluded with both teams presenting sharp exchanges, navigating regulatory grey areas and constitutional principles with poise. Judges appreciated the structured articulation but reserved more pointed questions for final rounds.

Court Hall-IV

The session in Courtroom 4 began with the Petitioners defending their practices regarding user consent and business model transparency. They stated that FlashRetail ensures informed consent is obtained from its users, particularly with respect to their Terms and Conditions (T&Cs), which govern how customers are treated once they stop using the app. The company clarified that the claim of delivering goods within 10 minutes on average is a marketing strategy and that no payment is required from users before the 10-minute window. They explained that disclaimers are used to ensure that customers understand this is not a guaranteed delivery time. FlashRetail emphasized that it strives to maintain a balance between transparency and innovation, with independent teams working on personalized algorithms to tailor the app’s services to each individual user.

The Bench inquired about the level of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the company, asking, “How much percent of FDI is involved in your company’s operations?” The Petitioners responded that as an inventory-based model, FlashRetail is compliant with FDI policies, and its FDI can be as high as 100%. They clarified that the company operates at a market level comparable to competitors and that there should be no discrimination simply because the company receives FDI, invoking the principle laid out in E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu (1974) to argue that no arbitrary discrimination should occur based on funding origin.

The Judge asked a crucial question regarding the ongoing investigation by the Enforcement Directorate (ED), “If the issue is already under investigation, why are you here? What is your locus to stand on as an inventory-based model?” The Petitioners defended their position, arguing that the investigation does not preclude them from engaging with this forum, and further stated that there should be no cap on FDI investments. They emphasized that the 10-minute delivery claim is a marketing tactic and should not be subject to legal scrutiny in the absence of evidence of malintent. Referencing the B.P. Sharma case, they pointed out that no blanket ban on professional activities is permissible under Indian law.

The Judge shifted focus to concerns about the company’s liability and treatment of delivery riders, asking, “What is the vicarious liability for the company regarding the riders? Why are customers being asked to pay for the insurance of riders?” Additionally, the Judge raised the issue of whether FlashRetail could be considered a dominant player in metropolitan markets and whether selling below cost price is legal under competition law. The Petitioners clarified that, according to the Competition Act, they are not a dominant player, even with a 45% market share in urban areas, and that other competitors must also be considered when determining market dominance. They further argued that they are not violating Section 4 of the Competition Act, as there is no evidence of anti-competitive behavior or market manipulation.

The Respondents presented their counterarguments, citing technical issues faced by the Enforcement Directorate in 2024. They emphasized that the investigation’s time frame should be considered in evaluating the matter. When the Judge asked whether the ED had jurisdiction over the matter and how FDI terms were violated, the Respondents clarified that it is a competition matter and questioned the constitutional validity of permitting 75% foreign investment in a domestic entity while imposing restrictions on foreign-funded entities. They argued that such distinctions could be constitutionally questionable and are detrimental to the business environment.

The Respondents also drew attention to the lack of FDI restrictions for supermarkets in Sindhu Pradesh, which focus on urban areas rather than rural ones. They questioned why the government does not impose similar restrictions on both online and offline entities, which would create a level playing field for all types of retail operations.

As the session concluded, the Bench remarked on the complexity of the issues discussed, noting that the case presents important questions regarding competition law, consumer protection, and regulatory fairness in the context of e-commerce and foreign investment.

TEAM QUALIFYING FOR SEMI-FINAL ROUNDS ARE

TC-2515

TC-2516

TC-2504

TC-2512

26th April 2025 (Day-2) 01:00 PM | Semi-Final Rounds| UG Block

Court Hall-I

The semifinal round commenced with the parties seeking permission from the Bench to proceed. Upon approval, the Counsel for the Petitioner initiated the arguments with Speaker 1 addressing Issue 1. The Speaker stated that the Petitioner is neither a business provider nor a seller, but a mere digital platform connecting buyers and sellers. The Speaker submitted that e-commerce platforms can provide over 60% of goods and emphasized that the cap on sellers and the provision of goods are completely different matters, thus not violating the FDI policy. The Judge pointed out that vendors are traders and not manufacturers, stressing that both should not be compared relatively.

The Speaker further argued that the cashback provided is fair and not arbitrary. However, the Judge intervened and stated that market entity protections must fall under Article 19 if constitutional challenges are raised, emphasizing the need for proper criteria. In response to allegations of FEMA violations, the Speaker cited the moot proposition and Schedule 7, highlighting that foreign entities are allowed to invest under the marketplace model according to FDI policy. The Speaker also asserted that the Flash Retail business model is legitimate and compliant with marketplace regulations and FEMA guidelines.

Citing Chiranjit Lal Chowdhuri v. Union of India and Chintaman Rao v. State of Madhya Pradesh, the Speaker emphasized the necessity of reasonable classification. The Bench then questioned whether Article 19 rights extend to organizations and why stakeholders themselves had not filed a complaint. The Speaker responded that the moot proposition was silent on this issue. When asked about the number of judges in the Chintaman Rao judgment, the Speaker could not answer.

Moving to another issue, the Appellant argued that drivers were trained for faster yet safe deliveries. The Judges questioned whether the faster delivery of goods could be considered a fundamental right violation. The Speaker asserted that it was linked to the right to trade. However, the Judges emphasized that trade rights were not being restricted here and asked the Speaker to present their best arguments within the remaining time. The Judges discussed the concept of negative equality and suggested that such cases should be filed in civil court instead.

Speaker 2 then addressed Issues 3, 4, and 5, clarifying that the marketplace provides services, and cited Section 3(4) of the Competition Commission Act regarding efficiency under the Consumer Protection Act. The Judges questioned the 45% market share figure, seeking clarification whether it referred to goods or services. The Speaker highlighted the pro-competitive nature of the marketplace, facilitating user accessibility, while addressing concerns about dark patterns and mentioning the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023.

The Respondent’s side began with Speaker 1 addressing Issues 1, 5, and 3. After obtaining permission from the Bench, the Respondent argued that the challenged rules were mere drafts and not “law” under Article 13 of the Constitution, and that enforcement of fundamental rights requires an actual violation, not just a potential threat. The Judges pressed for proper legal reasoning instead of political arguments. The Respondents acknowledged that 75% of the company’s share comes from FDI.

The Judges inquired about how the Respondent’s policy serves the public good. The Speaker discussed reasonable restrictions under Article 19 for public health, safety, and morality, raising concerns about the risks associated with 10-minute deliveries leading to rash driving among gig workers. When asked about evidence backing such claims, the Speaker referenced the Kharagpur case but was reminded by the Judges that consumer satisfaction with fast delivery cannot be ignored without data.

The last issue argued by the Respondent Speaker 1 cited MRF Limited v. Inspector Kerala Govt. & Ors. highlighting reasonable restrictions under Article 21 and referenced the landmark judgment in K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India. It was argued that Article 226 cannot be invoked without exhausting statutory remedies and reiterated the test of proportionality as established in K.S. Puttaswamy. The necessity of constant location access was questioned, citing a lack of sufficient explanation.

Speaker 2 for the Respondent then proceeded, taking permission and addressing Issue IV. Defining dark patterns, the Speaker mentioned techniques like basket sneaking and criticized Flash Retail’s practice of making it easy to sign up but difficult to delete an account, referencing the case Muniyappa Reddy K.N. v. State of Karnataka. The Judges pointed out issues with Flash Retail’s tagline changes, to which the Speaker responded by invoking Section 89 of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019. With this, the proceedings for Courtroom 1 came to an end.

Court Hall-II

The 1st Speaker for the Petitioner began by asserting that FlashRetail prompts on the app facilitate smoother transactions without misleading or nagging the users. The counsel emphasized that nudging is not equivalent to nagging and defended their “10-minute delivery” advertisements as a reflection of innovation needs, not a guarantee. They clarified that a disclaimer clearly mentioned that the delivery within 10 minutes was on an average basis, and goodwill cashbacks were provided if the timelines were not met. Algorithms, according to the counsel, were being used to enhance customer welfare.

The Judges questioned why the reasons for delivery delays were not transparently disclosed, particularly when they could be due to a shortage of delivery partners and criticized the lack of clarity in ordinary product pricing. They also pointed out inconsistencies in the company’s own audit practices.