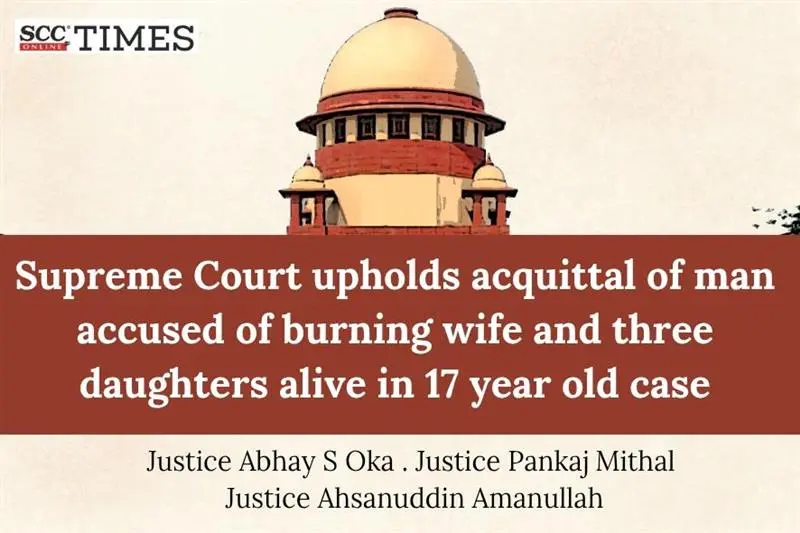

Supreme Court: In a criminal appeal filed against the judgment passed by the Allahabad High Court, wherein the accused was acquitted of the offence punishable under Section 302 of the Penal Code, 1860 (‘IPC’), the three-judge bench of Abhay S Oka*, Pankaj Mithal and Ahsanuddin Amanullah, JJ. upon reappreciating the evidence, found that the view taken by the High Court, that the prosecution had failed to prove the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt was a plausible and reasonable interpretation of the evidence on record. Even if an alternative view could be reasonably drawn from the same evidence, the Court reiterated that this alone does not justify overturning the order of acquittal. In criminal law, the benefit of doubt must go to the accused, and unless the evidence decisively proves guilt, the acquittal must stand.

Background

In 2008, a tragic incident led to the death of the accused’s wife and his three daughters due to severe burn injuries allegedly inflicted by the accused and his cousin, Aslam. According to the prosecution, the accused persons poured kerosene on the victims and set them on fire. Additionally, the co-accused (cousin of the accused) also succumbed to burn injuries sustained in the same incident.

In 2014, the Trial Court convicted the accused, primarily relying on the testimony of his minor son and the dying declarations of the victims. The Court imposed the death penalty on the accused.

However, in 2015, the Allahabad High Court reversed the conviction and acquitted the accused finding that the prosecution had failed to establish guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. By the impugned judgment, the High Court not only declined to confirm the sentence of capital punishment awarded by the Trial Court but also proceeded to acquit the accused of all charges.

Following this acquittal, the wife’s brother (the complainant) and the State of Uttar Pradesh filed criminal appeals before this Court, challenging the High Court’s decision.

Analysis and Decision

The Court noted that the Trial Judge administered the oath to the accused’s son and recorded his deposition without first satisfying himself of the minor’s competence to testify. This procedural lapse casts serious doubt on the reliability of the son’s testimony, particularly given the ease with which a minor witness may be influenced or tutored. Furthermore, the Court noted material contradictions in the son’s statements, which were substantiated by the testimony of the investigating officer.

Upon examining the dying declarations of the deceased daughters of the accused, the Court observed significant procedural irregularities. The Tahsildar, who recorded the statements, admitted that he did not read the declarations back to the victims after recording them. Furthermore, while the attending doctor endorsed that both victims were “fit,” there was no specific certification that they were in a mental and physical condition to make a coherent statement at the time.

Most notably, the Court found that the contents of the dying declarations, as testified by the Tahsildar, were not put to the accused during his examination under Section 313 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (‘CrPC’).

The Court observed that the prosecution had placed substantial reliance on the dying declarations of the two victims. However, since this evidence was not brought to the attention of the accused during his examination under Section 313 CrPC, he was denied a fair opportunity to offer an explanation or rebuttal. This omission, the Court noted, caused clear prejudice to the accused. As a result, the Court held that the dying declarations could not be considered as admissible evidence and must be excluded from the evidentiary record.

The Court noted that the incident in question occurred on 26-12-2008. Even assuming that the omission to put relevant evidence to the accused under Section 313 CrPC is curable, the critical question is whether, after a lapse of more than 14 years, the case can justifiably be remanded to the Trial Court for further examination of the accused under the said provision. The Court observed that compelling the accused to undergo such an examination after such an inordinate delay would be manifestly unjust.

It was further noted that the accused had already undergone more than six years of incarceration, and from the date of the Trial Court’s judgment until the pronouncement of the impugned judgment, he lived under the looming threat of capital punishment. In light of these circumstances, the Court held that directing a remand at this belated stage would cause serious prejudice to the accused.

Although the Court did not concur with all the findings of the High Court, it found no fault with the ultimate conclusion arrived at.

The Court also highlighted two significant aspects that had been overlooked. First, it noted that the co-accused (cousin of the accused), had also sustained burn injuries during the incident and subsequently died on 2-01-2009 due to septicaemia, having suffered approximately 40% burn injuries. Second, the Court found that the prosecution had suppressed the fact that the accused himself had sustained superficial to deep burn injuries on his face and both forearms, amounting to approximately 20% burns. This fact was not brought on record by the prosecution but was established by the defence through the testimony of the doctor, who appeared as a defence witness.

The Court noted a significant flaw in the prosecution’s case. According to the prosecution, after allegedly pouring kerosene oil on the victims, the accused and his co-accused were said to have stood outside the room, preventing anyone from entering. However, it is important to note that the co-accused himself was a victim of the fire, sustaining fatal burn injuries. The prosecution failed to provide any plausible explanation for how both the accused and the co-accused sustained their burn injuries. The fatal nature of co-accused’s injuries, coupled with the lack of clarity surrounding the cause of these injuries, raised serious doubts about the prosecution’s version of events and further cast suspicion on the case against the accused.

The Court emphasised that this was an appeal against acquittal. Upon reappreciating the evidence, the Court found that the view taken by the High Court, that the prosecution had failed to prove the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt was a plausible and reasonable interpretation of the evidence on record. Even if an alternative view could be reasonably drawn from the same evidence, the Court reiterated that this alone does not justify overturning the order of acquittal. In criminal law, the benefit of doubt must go to the accused, and unless the evidence decisively proves guilt, the acquittal must stand.

The Court acknowledged the shocking nature of the incident, in which a woman and her three daughters were tragically burnt, with one daughter dying on the spot and the others succumbing to their injuries shortly thereafter. However, despite the severity of the crime, the Court emphasized that in the absence of legally admissible evidence to prove the guilt of the accused beyond a reasonable doubt, it could not interfere with the impugned judgment of the High Court. The Court reaffirmed that the law requires proof beyond doubt, and without such evidence, the acquittal must stand.

The Court observed that numerous criminal appeals brought before it reveals a recurring issue—vital prosecution evidence is often not put to the accused during their examination under Section 313 CrPC. In such cases, the Court finds itself in a difficult position, as the defect caused by this omission cannot be rectified, especially when a long period has passed. The Court pointed to its earlier decision in Raj Kumar v. State (NCT of Delhi), where this very issue was addressed, highlighting the consequences of such procedural lapses.

The Court further suggested that when an appeal against conviction was filed before the High Court, it should, at the earliest opportunity, have examined whether the accused’s statement under Section 313 CrPC (Section 351 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023), had been properly recorded. If any defect in the recording of the statement was identified, the High Court could have taken remedial action by either recording a further statement of the accused or by directing the Trial Court to do so. By adopting this approach, the issue of delay and subsequent prejudice to the accused would have been avoided, ensuring that the accused was not disadvantaged by procedural lapses that occurred during the trial stage.

CASE DETAILS

|

Citation: Appellants : Respondents : |

Advocates who appeared in this case For Petitioner(s): For Respondent(s): |

CORAM :